Modeling teacher self-efficacy as a function of peer observation, administrative feedback, job satisfaction, and work enjoyment

This study used a large‐scale, international data set – the Organization for Economic Co‐

operation and Development (OECD) – Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2013, consist‐

ing of 14,583 teachers from 34 countries – to examine the manner in which feedback from administrators,

time spent observing colleagues’ classes, job satisfaction, and work enjoyment predicted teachers’ instruc‐

tional self‐efficacy. To guide the present study, Bandura’s (1986, 1997) part of the social cognitive theory –

that is, self‐efficacy theory – is utilized. We adopted Bandura’s self‐efficacy theory as the framework, for it

provides a valuable lens through which we could identify the predictors of teacher self‐efficacy to include

in the model investigated in this study. The results of this study suggest that feedback from administrators

was not a significant predictor of teacher self‐efficacy for instruction, whilst peer observation, job satisfac‐

tion, and work enjoyment were estimated as being significant predictors. These results have implications

for practice – specifically, how teachers and school leaders should cultivate teachers’ self‐efficacy for in‐

struction – and future research.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Modeling teacher self-efficacy as a function of peer observation, administrative feedback, job satisfaction, and work enjoyment

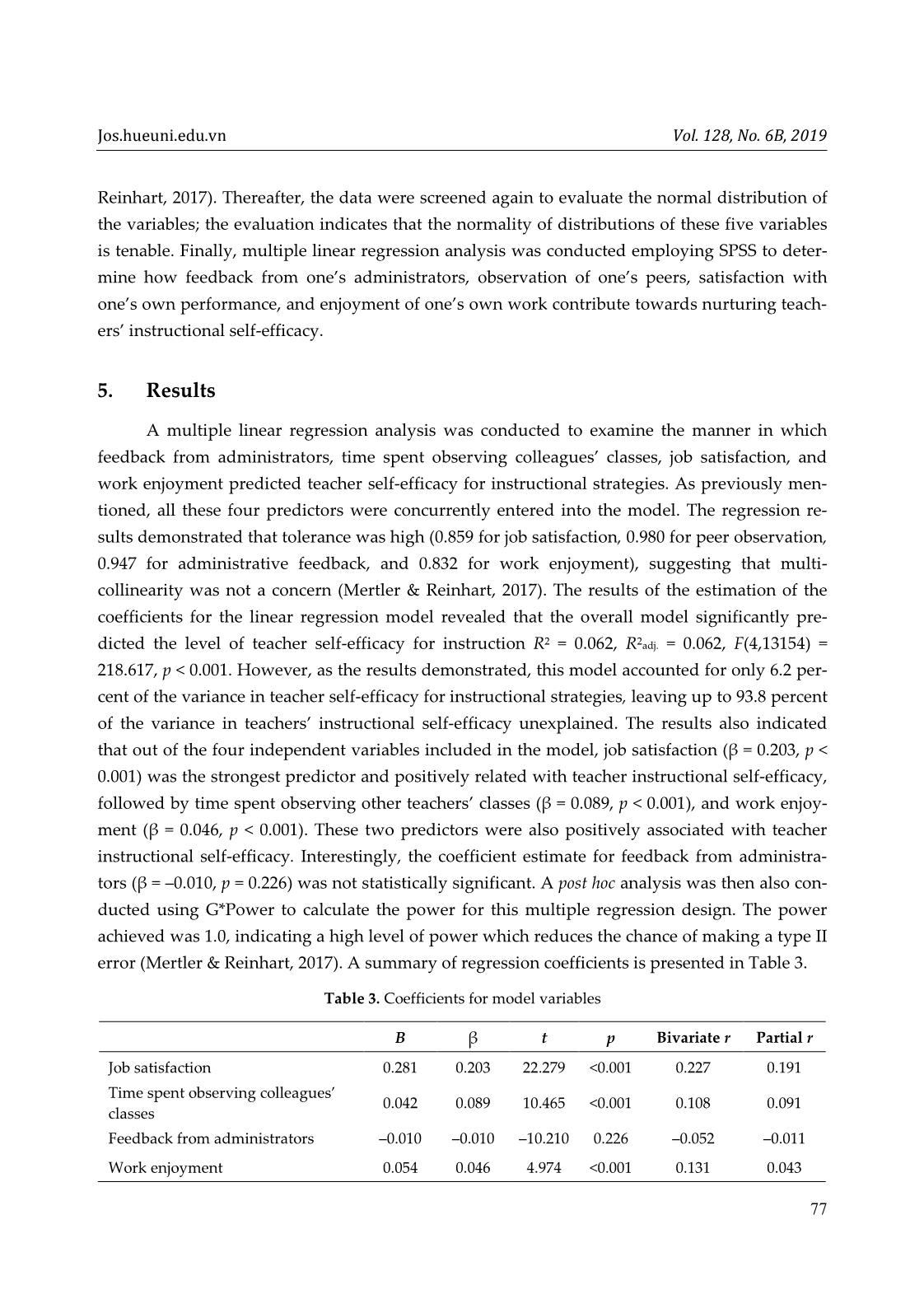

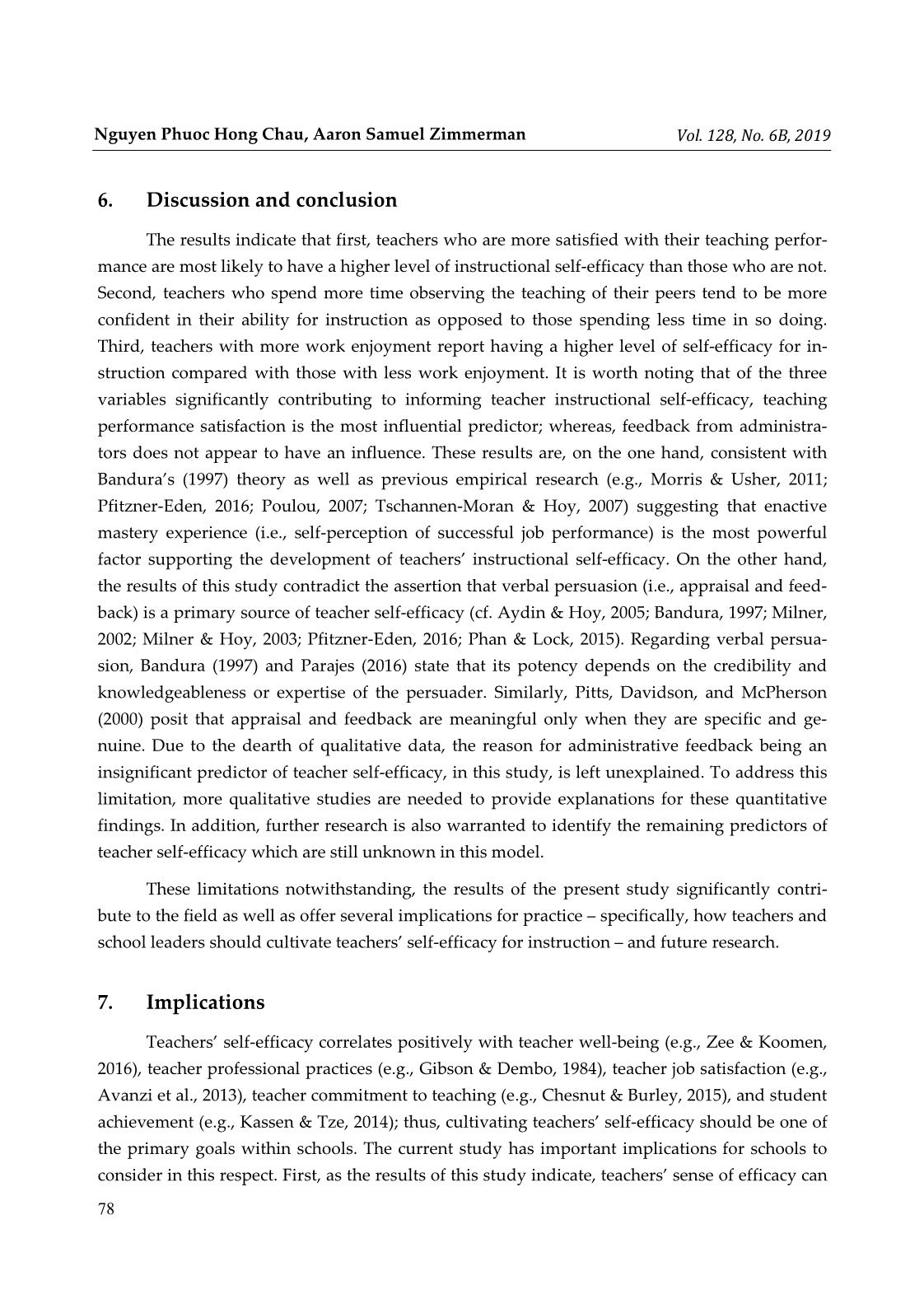

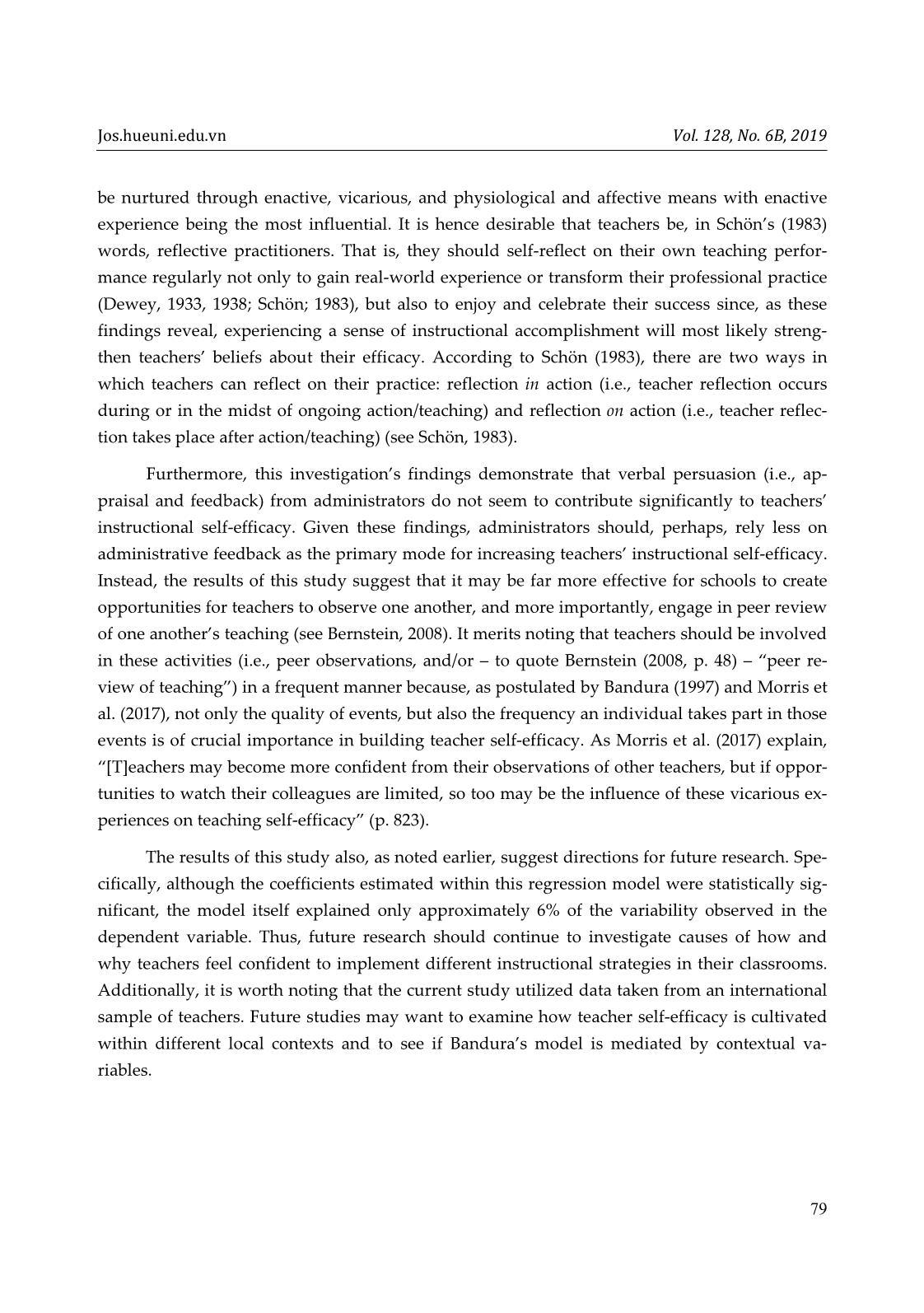

43 Nguyen Phuoc Hong Chau, Aaron Samuel Zimmerman Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 78 6. Discussion and conclusion The results indicate that first, teachers who are more satisfied with their teaching perfor‐ mance are most likely to have a higher level of instructional self‐efficacy than those who are not. Second, teachers who spend more time observing the teaching of their peers tend to be more confident in their ability for instruction as opposed to those spending less time in so doing. Third, teachers with more work enjoyment report having a higher level of self‐efficacy for in‐ struction compared with those with less work enjoyment. It is worth noting that of the three variables significantly contributing to informing teacher instructional self‐efficacy, teaching performance satisfaction is the most influential predictor; whereas, feedback from administra‐ tors does not appear to have an influence. These results are, on the one hand, consistent with Bandura’s (1997) theory as well as previous empirical research (e.g., Morris & Usher, 2011; Pfitzner‐Eden, 2016; Poulou, 2007; Tschannen‐Moran & Hoy, 2007) suggesting that enactive mastery experience (i.e., self‐perception of successful job performance) is the most powerful factor supporting the development of teachers’ instructional self‐efficacy. On the other hand, the results of this study contradict the assertion that verbal persuasion (i.e., appraisal and feed‐ back) is a primary source of teacher self‐efficacy (cf. Aydin & Hoy, 2005; Bandura, 1997; Milner, 2002; Milner & Hoy, 2003; Pfitzner‐Eden, 2016; Phan & Lock, 2015). Regarding verbal persua‐ sion, Bandura (1997) and Parajes (2016) state that its potency depends on the credibility and knowledgeableness or expertise of the persuader. Similarly, Pitts, Davidson, and McPherson (2000) posit that appraisal and feedback are meaningful only when they are specific and ge‐ nuine. Due to the dearth of qualitative data, the reason for administrative feedback being an insignificant predictor of teacher self‐efficacy, in this study, is left unexplained. To address this limitation, more qualitative studies are needed to provide explanations for these quantitative findings. In addition, further research is also warranted to identify the remaining predictors of teacher self‐efficacy which are still unknown in this model. These limitations notwithstanding, the results of the present study significantly contri‐ bute to the field as well as offer several implications for practice – specifically, how teachers and school leaders should cultivate teachers’ self‐efficacy for instruction – and future research. 7. Implications Teachers’ self‐efficacy correlates positively with teacher well‐being (e.g., Zee & Koomen, 2016), teacher professional practices (e.g., Gibson & Dembo, 1984), teacher job satisfaction (e.g., Avanzi et al., 2013), teacher commitment to teaching (e.g., Chesnut & Burley, 2015), and student achievement (e.g., Kassen & Tze, 2014); thus, cultivating teachers’ self‐efficacy should be one of the primary goals within schools. The current study has important implications for schools to consider in this respect. First, as the results of this study indicate, teachers’ sense of efficacy can Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 79 be nurtured through enactive, vicarious, and physiological and affective means with enactive experience being the most influential. It is hence desirable that teachers be, in Schön’s (1983) words, reflective practitioners. That is, they should self‐reflect on their own teaching perfor‐ mance regularly not only to gain real‐world experience or transform their professional practice (Dewey, 1933, 1938; Schön; 1983), but also to enjoy and celebrate their success since, as these findings reveal, experiencing a sense of instructional accomplishment will most likely streng‐ then teachers’ beliefs about their efficacy. According to Schön (1983), there are two ways in which teachers can reflect on their practice: reflection in action (i.e., teacher reflection occurs during or in the midst of ongoing action/teaching) and reflection on action (i.e., teacher reflec‐ tion takes place after action/teaching) (see Schön, 1983). Furthermore, this investigation’s findings demonstrate that verbal persuasion (i.e., ap‐ praisal and feedback) from administrators do not seem to contribute significantly to teachers’ instructional self‐efficacy. Given these findings, administrators should, perhaps, rely less on administrative feedback as the primary mode for increasing teachers’ instructional self‐efficacy. Instead, the results of this study suggest that it may be far more effective for schools to create opportunities for teachers to observe one another, and more importantly, engage in peer review of one another’s teaching (see Bernstein, 2008). It merits noting that teachers should be involved in these activities (i.e., peer observations, and/or – to quote Bernstein (2008, p. 48) – “peer re‐ view of teaching”) in a frequent manner because, as postulated by Bandura (1997) and Morris et al. (2017), not only the quality of events, but also the frequency an individual takes part in those events is of crucial importance in building teacher self‐efficacy. As Morris et al. (2017) explain, “[T]eachers may become more confident from their observations of other teachers, but if oppor‐ tunities to watch their colleagues are limited, so too may be the influence of these vicarious ex‐ periences on teaching self‐efficacy” (p. 823). The results of this study also, as noted earlier, suggest directions for future research. Spe‐ cifically, although the coefficients estimated within this regression model were statistically sig‐ nificant, the model itself explained only approximately 6% of the variability observed in the dependent variable. Thus, future research should continue to investigate causes of how and why teachers feel confident to implement different instructional strategies in their classrooms. Additionally, it is worth noting that the current study utilized data taken from an international sample of teachers. Future studies may want to examine how teacher self‐efficacy is cultivated within different local contexts and to see if Bandura’s model is mediated by contextual va‐ riables. Nguyen Phuoc Hong Chau, Aaron Samuel Zimmerman Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 80 References 1. Anderson, R. N., Greene, M. L., & Loewen, P. S. (1988). Relationships among teachers’ and students’ thinking skills, sense of efficacy, and student achievement. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 34(8), 148–165. 2. Avanzi, L., Miglioretti, M., Velasco, V., Balducci, C., Vecchio, L., Fraccaroli, F., & Skaal‐ vik, E. M. (2013). Cross‐validation of the Norwegian teacher's self‐efficacy scale (NTSES). Teaching and Teacher Education, 31(3), 69–78. 3. Aydin, Y. C., & Hoy, A. W. (2005). What predicts student teacher self‐efficacy? Academic Exchange Quarterly, 9(4), 123–127. 4. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. New Jersey, NJ: Prentice‐Hall, Inc. 5. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman. 6. Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self‐efficacy scales. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Ado- lescents, 5(1), 307–337. 7. Bernstein, D. J. (2008). Peer review and evaluation of the intellectual work of teach‐ ing. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 40(2), 48–51. 8. Betoret, F. D. (2006). Stressors, self‐efficacy, coping resources, and burnout among sec‐ ondary school teachers in Spain. Educational Psychology, 26(4), 519–539. 9. Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self‐efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(3), 239–25. 10. Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., & Steca, P. (2003). Efficacy beliefs as deter‐ minants of teachers' job satisfaction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 821–832. 11. Chesnut, S. R., & Burley, H. (2015). Self‐efficacy as a predictor of commitment to the teaching profession: A meta‐analysis. Educational Research Review, 15, 1–16. 12. Chwalisz, K., Altmaier, E. M., & Russell, D. W. (1992). Causal attributions, self‐efficacy cognitions, and coping with stress. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,11(9), 377–400. 13. Coladarci, T. (1992). Teachers' sense of efficacy and commitment to teaching. The Journal of Experimental Education, 60(4), 323–337. 14. Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. New Jersey, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 81 15. Dembo, M. H., & Gibson, S. (1985). Teachers’ sense of efficacy: An important factor in school improvement. The Elementary School Journal, 86(2), 173–184. 16. Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educa- tive process. Boston, MA: Heath. 17. Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY: Macmillan. 18. Evans, E. D., & Tribble, M. (1986). Perceived teaching problems, self‐efficacy, and com‐ mitment to teaching among preservice teachers. The Journal of Educational Research, 80(2), 81–85. 19. Evers, W. J., Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2002). Burnout and self‐efficacy: A study on teachers' beliefs when implementing an innovative educational system in the Nether‐ lands. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(2), 227–243. 20. Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. 21. Gibson, S., & Dembo, M. H. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(8), 669–682. 22. Hendricks, K. S. (2016). The sources of self‐efficacy: Educational research and implica‐ tions for music. National Association for Music Education, 35(1), 32–38. 23. Johnson, D. (2010). Learning to teach: The influence of a university‐school partnership project on pre‐service elementary teachers’ efficacy for literacy instruction. Reading Hori- zons, 50(1), 23–48. 24. Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers’ self‐efficacy, personality, and teaching ef‐ fectiveness: A meta‐analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76. 25. Klassen, R. M., & Usher, E. L. (2010). Self‐efficacy in educational settings: Recent research and emerging directions. In T. C. Urdan & S. A. Karabenick (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement: Vol. 16A. The decade ahead: Theoretical perspectives on motivation and achievement (pp. 1–33). Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Group. 26. Mertler, C. A., & Reinhart, R. V. (2017). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: Prac- tical application and interpretation. New York, NY: Routledge. 27. Mills, N. (2011). Teaching assistants’ self‐efficacy in teaching literature: Sources, personal assessments, and consequences. The Modern Language Journal, 95(1), 61–80. 28. Milner, H. R. (2002). A case study of an experienced English teacher’s self‐efficacy and persistence through “crisis” situations: Theoretical and practical considerations. The High School Journal, 86(1), 28–35. Nguyen Phuoc Hong Chau, Aaron Samuel Zimmerman Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 82 29. Milner, H. R., & Hoy, A. W. (2003). A case study of an African American teacher’s self‐ efficacy, stereotype threat, and persistence. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(2), 263–276. 30. Morris, D. B., & Usher, E. L. (2011). Developing teaching self‐efficacy in research institu‐ tions: A study of award‐winning professors. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(3), 232–245. 31. Morris, D. B., Usher, E. L., & Chen, J. A. (2017). Reconceptualizing the sources of teaching self‐efficacy: A critical review of emerging literature. Educational Psychology Review, 29(4), 795–833. 32. OECD. (2014). TALIS 2013 results: An international perspective on teaching and learning. Par‐ is: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/talis‐2013‐ results.htm 33. Pajares, F. (2006). Self‐efficacy during childhood and adolescence: Implications for teach‐ ers and parents. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 117– 137). Greenwich: Information Age Publishing. 34. Palmer, D. H. (2006). Sources of self‐efficacy in a science methods course for primary teacher education students. Research in Science Education, 36(4), 337–353. 35. Pfitzner‐Eden, F. (2016). Why do I feel more confident? Bandura’s sources predict preser‐ vice teachers’ latent changes in teacher self‐efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–16. 36. Phan, N. T. T., & Locke, T. (2015). Sources of self‐efficacy of Vietnamese EFL teachers: A qualitative study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 52, 73–82. 37. Pitts, S. E., Davidson, J. W., & McPherson, G. E. (2000). Models of success and failure in instrumental learning: Case studies of young players in the first 20 months of learn‐ ing. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 146, 51–69. 38. Poulou, M. (2007). Personal teaching efficacy and its sources: Student teachers’ percep‐ tions. Educational Psychology, 27(2), 191–218. 39. Ross, J. A. (1992). Teacher efficacy and the effects of coaching on student achievement. Canadian Journal of Education, 17(1), 51–65. 40. Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York, NY: Basic Books. 41. Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2009). Does school context matter? Relations with teacher burnout and job satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(9), 518–524. Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 83 42. Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self‐efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1059–1069. 43. Tschannen‐Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2007). The differential antecedents of self‐efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(6), 944–956. 44. Tschannen‐Moran, M., & Johnson, D. (2011). Exploring literacy teachers’ self‐efficacy be‐ liefs: Potential sources at play. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2), 751–761. 45. Tschannen‐Moran, M., & McMaster, P. (2009). Sources of self‐efficacy: Four professional development formats and their relationship to self‐efficacy and implementation of a new teaching strategy. The Elementary School Journal, 110(2), 228–245. 46. Urdan, T. C. (2017). Statistics in plain English. New York, NY: Routledge. 47. Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self‐efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well‐being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86, 981–1015.

File đính kèm:

modeling_teacher_self_efficacy_as_a_function_of_peer_observa.pdf

modeling_teacher_self_efficacy_as_a_function_of_peer_observa.pdf