Should Vietnamese EFL learners have English names?

In this paper, I investigate the practice of selecting English names for Vietnamese EFL learners at a language centre. Although this naming practice is required at the institution for communicative convenience, there is negotiation and exceptions where learners refuse to use English names. Naming is believed to reflect one’s identity, and those learners explicitly indicate numerous reasons for their acceptance or refusal of having English names. Observations and interviews with 15 participants in an EFL class were undertaken to explore the attitudes and reasons for their naming practices and their identity reflection through that practice. The findings reveal that most learners see English names to be more convenient for their native English-Speaking teachers and make them feel more westernised, which is, in their belief, necessary in an EFL setting. On the contrary, some learners would show respect to their Vietnamese names, which they believe to be meaningful and should be maintained. Whether using an English name as an act of showing respect or not in EFL settings is also discussed. Also, regardless of genders, the paper reveals the age issue that strongly impacts the naming decision. The paper concludes with suggestions for the proper naming practice among EFL learners so as not to make learners feel discontent in their learning processes

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Should Vietnamese EFL learners have English names?

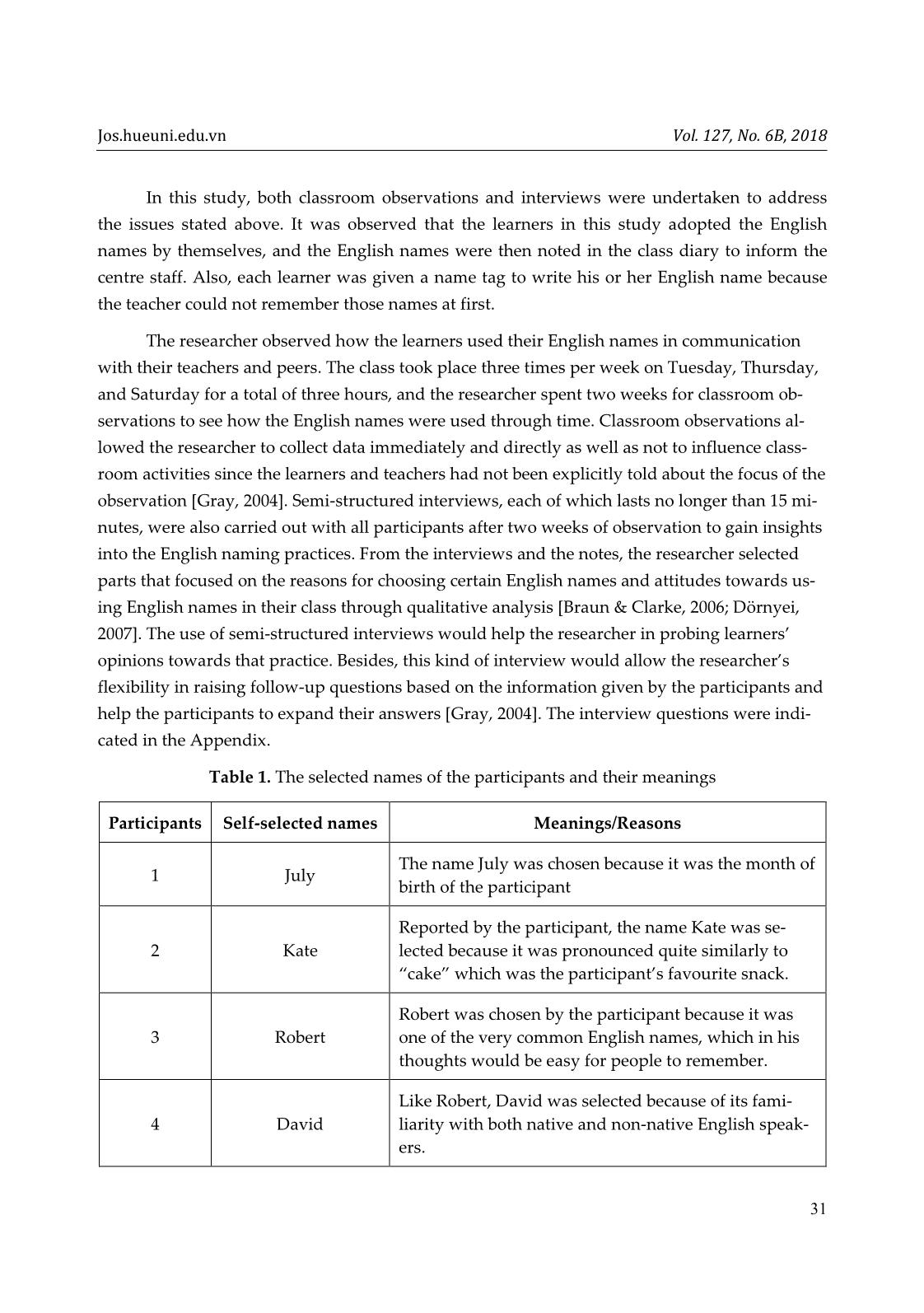

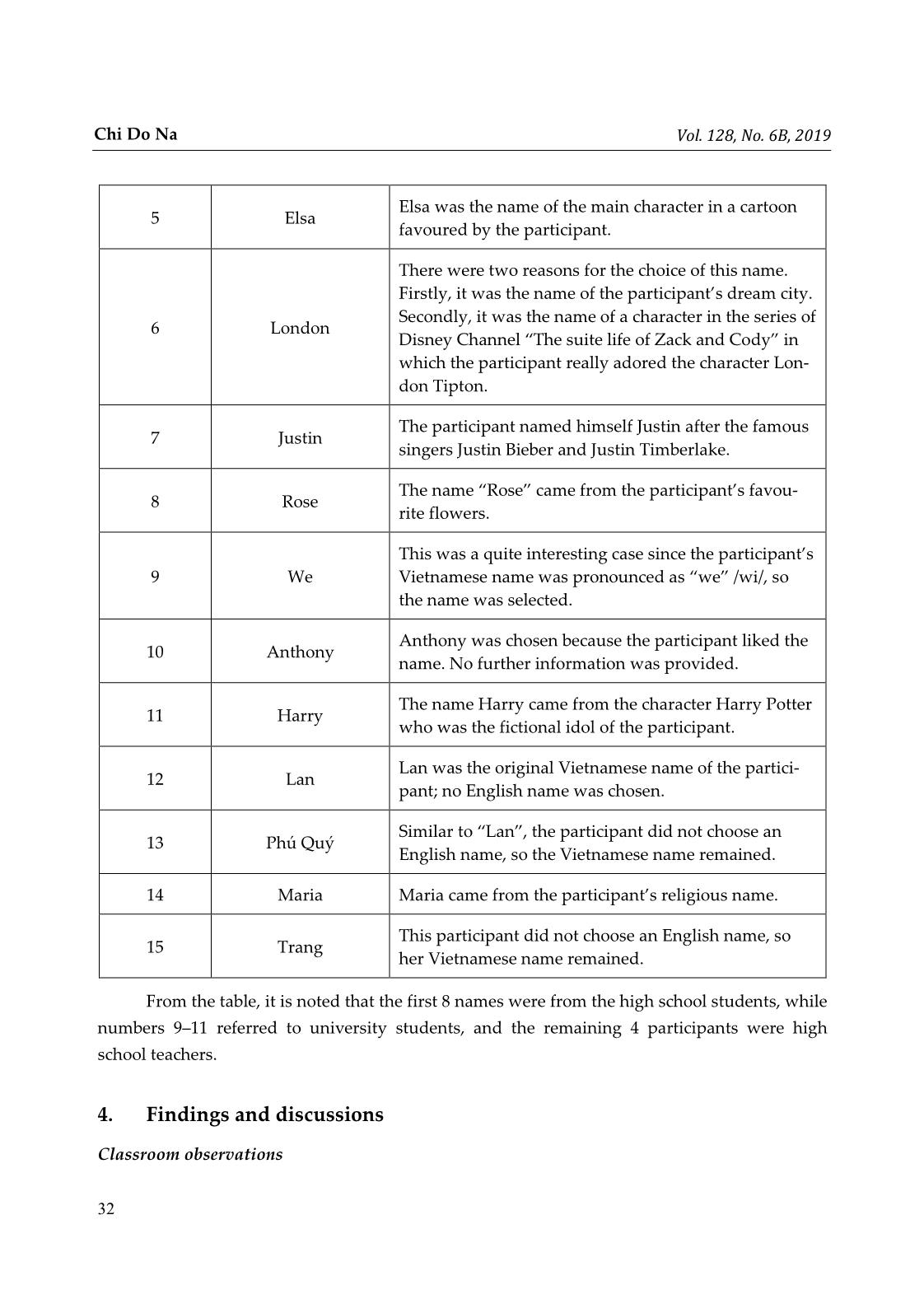

r classroom ob- servations to see how the English names were used through time. Classroom observations al- lowed the researcher to collect data immediately and directly as well as not to influence class- room activities since the learners and teachers had not been explicitly told about the focus of the observation [Gray, 2004]. Semi-structured interviews, each of which lasts no longer than 15 mi- nutes, were also carried out with all participants after two weeks of observation to gain insights into the English naming practices. From the interviews and the notes, the researcher selected parts that focused on the reasons for choosing certain English names and attitudes towards us- ing English names in their class through qualitative analysis [Braun & Clarke, 2006; Dörnyei, 2007]. The use of semi-structured interviews would help the researcher in probing learners’ opinions towards that practice. Besides, this kind of interview would allow the researcher’s flexibility in raising follow-up questions based on the information given by the participants and help the participants to expand their answers [Gray, 2004]. The interview questions were indi- cated in the Appendix. Table 1. The selected names of the participants and their meanings Participants Self-selected names Meanings/Reasons 1 July The name July was chosen because it was the month of birth of the participant 2 Kate Reported by the participant, the name Kate was se- lected because it was pronounced quite similarly to “cake” which was the participant’s favourite snack. 3 Robert Robert was chosen by the participant because it was one of the very common English names, which in his thoughts would be easy for people to remember. 4 David Like Robert, David was selected because of its fami- liarity with both native and non-native English speak- ers. Chi Do Na Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 32 From the table, it is noted that the first 8 names were from the high school students, while numbers 9–11 referred to university students, and the remaining 4 participants were high school teachers. 4. Findings and discussions Classroom observations 5 Elsa Elsa was the name of the main character in a cartoon favoured by the participant. 6 London There were two reasons for the choice of this name. Firstly, it was the name of the participant’s dream city. Secondly, it was the name of a character in the series of Disney Channel “The suite life of Zack and Cody” in which the participant really adored the character Lon- don Tipton. 7 Justin The participant named himself Justin after the famous singers Justin Bieber and Justin Timberlake. 8 Rose The name “Rose” came from the participant’s favou- rite flowers. 9 We This was a quite interesting case since the participant’s Vietnamese name was pronounced as “we” /wi/, so the name was selected. 10 Anthony Anthony was chosen because the participant liked the name. No further information was provided. 11 Harry The name Harry came from the character Harry Potter who was the fictional idol of the participant. 12 Lan Lan was the original Vietnamese name of the partici- pant; no English name was chosen. 13 Phú Quý Similar to “Lan”, the participant did not choose an English name, so the Vietnamese name remained. 14 Maria Maria came from the participant’s religious name. 15 Trang This participant did not choose an English name, so her Vietnamese name remained. Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 127, No. 6B, 2018 33 All participants in the study and their teachers used the selected names mentioned in Ta- ble 1 in their communication. Even for the staff, they also used these names when they ad- dressed the participants. They understood that the names they had selected would be their rep- resentatives throughout the program at the centre. Even, some of them stated that they enjoyed being called by these names outside their classroom settings. Interviews Theme 1: Learners’ names and representations In alignment with Cheang [2008], Fischer [2015], and Watzlawik et al. [2016], most partic- ipants were happy with having English names as a convenience in communication with English speakers. Some of them, despite having no specific reasons for their choices, tended to choose common names so that their peers and teachers can call and remember easily. Notably, a con- sensus was found between the participants’ choices of names and the ideas of self- representation proposed by Cheang [2008], Watzlawik et al. [2016], and Starks et al. [2012]. In detail, the selected names reflected the participants’ identities through their personal prefe- rences such as their idols, characters, food, birthday, places, and flowers (Participants 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11) and religious belief like Participant 14. The interviews with these participants also indi- cated that the selection of names was mostly based on two issues, namely their self- representations and the familiarity of the names. I choose July because I am [was] born in July. So, people can remember my name and my birthday. I think the name July is very easy to say and to remember. (Participant 1) I am Christian, so I was given, I think the holy name, as Maria. I think this is a very beautiful and meaningful name. It is popular, too. So, I choose this name. (Participant 14) Most participants admitted that they had never used English names before; hence, to make it easy for themselves and the people they talked to, choosing names that could mark their features can make people remember them better, and familiar names would also ensure accuracy in name calling and memorising. I actually do not know what name in English to choose, but I usually see the name David in many English books. So, I choose it. I think it is a popular and simple name. (Par- ticipant 4) Although much research has been performed into naming practices, little has been known about cases where some adaptations or negotiations in naming are made. For example, Participant 2 named herself on the basis of her favourite food (cake) with a slight change to make her name become more usual to the interlocutors. When being interviewed, she comfort- Chi Do Na Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 34 ably expressed that the meaning of her English name would be so memorable to her teachers and peers. I love cake, but I cannot use it for my name because it is so funny, so I change to Kate. I think when we say it, it is similar to “cake”. Participant 9 also got his name based on the Southern Vietnamese pronunciation of his name, i.e., “Quy” with its homophone in English. Explained by him, “We” was a perfect choice because both Vietnamese and English speakers could say the name easily, and it seemed that he did not change his name in terms of the pronunciation of Southern Vietnam accent. He believed that his Vietnamese identity remained with this name. I like my English name because it is special. I have never thought of anyone named We. I did not choose this name, but I just remember there is a word in English with the same sound. When people call me in my English and Vietnamese names, they are similar. So, it is interesting. However, unlike what previous research concludes on being content with having English names [Cheang, 2008; Watzlawik et al., 2016], there were still some participants who were not interested in this English naming. I think my name is easy to say already, and I do not know what English name to choose. I think we do not need to have an English name. Vietnamese name is okay, too, be- cause we need names to know that people are calling us. I am not comfortable when I use an English name with Vietnamese people, why not a Vietnamese name? (Participant 12) Interviewed about not choosing an English name, Participants 12, 13, and 15 commented that they thought English names would be more appropriate for teenagers, not for adults. This idea is similar to what Starks et al. [2012] mentioned about adolescents’ great concern about having nicknames representing their identities. I think young people can have English names. I think it is popular now. I see that many young people have English names on Facebook and they call their friends in [by] English names. But, I think it is not good for old people because I think people will laugh [at] us if we have an English name. They think that we are trying to be young. We are old now. (Participant 12) In fact, EFL adult learners’ naming practices have not been deeply investigated, and the matter of age in naming practices needs further exploration. In this study, they reminded that there was no need to have English names since trying to say other people’s names in their mother tongue was an indication of respect. Therefore, those participants would like to be called with their Vietnamese names by both the teachers and peers. In addition, Participant 13 Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 127, No. 6B, 2018 35 believed that his name meant “Prosperity”, which was so meaningful that it should not be changed. My name is very meaningful, and I love it. So, I don’t think I should change my name. I think we just use Vietnamese names, it is enough. All three participants further declared that their Vietnamese names were not too difficult to say. Hence, maintaining their Vietnamese names would be much preferred. Theme 2: EFL learners’ perceptions of English names When being asked about whether having English names is a good practice in EFL set- tings, a consensus was found among the participants. All of them agreed that English names should be optional or only personal preferences in EFL settings. I like to have an English name, but I am okay if people call me by English or Vietnam- ese names because I will know they are talking to me. Some people in class do not have Eng- lish names, maybe they don’t like them. But no problem because we can call by their Viet- namese name (Participant 3) The primary point was that people should be able to use the names that they are com- fortable with, and respect should be paid to whatever names they have. In communication, it is the responsibility to correctly remember and speak out the names of the interlocutors, which is much better and preferred than suggesting changes in names for better communication. I think we already introduced our Vietnamese name and I see that my English teacher can say our Vietnamese names. We do not need to change it because I do not think we ask people [to] change a name just because we cannot say it. In my class at school, there are some ethnic students, their names are hard to say but I need to learn, too. I cannot ask them to change names. (Participant 15) 5. Conclusion and suggestions Having English names is popular and preferable for most learners to make communica- tion more convenient for both the teacher and the learners. In addition, the refusals of having English names of some participants highlight the influences of ages and the respect for Viet- namese names, which previous research has not widely investigated. In terms of the reasons for English name choice, this study indicates a relationship between names, identities, and cultur- al. Because the names, both original and adopted ones, are so meaningful to learners that they think naming practices and name addressing is an indication of the respect in communication. Chi Do Na Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 36 On the other hand, previous research emphasises on identity reflection in choosing names; the study points out the choice of names thanks to the names’ familiarity and popularity with no references to identity, which is an addition to the diversity in naming practices. The study demonstrates Vietnamese EFL learners’ naming practices in an EFL setting and the reasons. Although not all participants agreed to pick English names for themselves, it is obvious that names, in many languages and to some extent, are meaningful to them and represent their identities. Since the requirement on having English names is not completely sa- tisfied at the centre, the suggestions to make are the respect to learners’ selection of their names and the need to address their preferred names properly regardless of their languages. This is a way of showing respect to the learners and their identities and to provide them with comfort in their study and communication. The current study also raises the issue of age in naming prac- tices and the negotiation between the meaning and familiarity of the names to the interlocutors. Further research may focus on these issues for a more complete view of naming practices. References 1. Agyekum, K. (2006), The sociolinguistic of Akan personal names. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 15(2), 206–235. 2. Ainiala, T. (2012), Place names and identities: The uses of names in Helsinki. In B. Hellel- and, C. Ore & S. Wikstrøm (eds.), Names and Identities. University of Olso. 3. Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006), Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101 4. Cheang, J. (2008), Choice of foreign name as a strategy for identity management. Intercul- tural Communication Studies, 17(2), 197– 202 5. Dörnyei, Z. (2007), Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 6. Erikson, E. (1968), Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. 7. Fischer, R. (2015), English personal names in international contexts. Journal of Theoretical Linguistics, 12(3), 238–256. 8. Gray, D. (2004), Doing research in the real world. SAGE Publications. 9. Guma, M. (2001), The cultural meaning of names among Basotho of Southern Africa: A historical and linguistic analysis. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 10(3), 265–279. 10. Kaplan, D. M. & Fisher, J. E. (2009), A rose by any other name: Identity and impression management in resumes. Employ Respons Rights, 21, 319–332. Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 127, No. 6B, 2018 37 11. Lawson, E.D. (1987), Personal names and naming: An annotated bibliography. New York: Greenwood. 12. Starks, D., Taylor-Leech, K., & Willoughby, L. (2012), Nicknames in Australian secondary schools: Insights into nicknames and adolescent views of self. Names, 60(3), 135–149. 13. Watzlawik, M., Guimaraes, D. S., Han, M. & Jung, A. E. (2016), First names as signs of personal identity: An intercultural comparison. Psychology and Society, 8(1), 1–21. Appendix. Interview questions 1. How long have you learned English? 2. Do you have an English name? - If Yes, please explain why you chose that name. - If No, please explain why you do not have one. 3. Do you think we should use English names in our English classes? Why (not)?

File đính kèm:

should_vietnamese_efl_learners_have_english_names.pdf

should_vietnamese_efl_learners_have_english_names.pdf