Giảng dạy môn Phiên dịch 1 tại khoa Ngoại ngữ: Đánh giá tổng quan và đề xuất hoạt động

Các khóa học phiên dịch đóng vai trò quan trọng trong nhiều chương trình đào tạo ở các trường đại

học Việt Nam; tuy nhiên, có rất ít các tài liệu và nghiên cứu về lĩnh vực này. Tác giả đã thực hiện

một nghiên cứu định tính nhằm tìm hiểu khóa học phiên dịch được thiết kế và giảng dạy tại Khoa

Ngoại ngữ như thế nào. Tác giả so sánh và phân tích đề cương của khóa học với bài kiểm tra

chuẩn quốc tế NAATI, sử dụng bảng câu hỏi và dự giờ giáo viên để thu thập dữ liệu. Các kết quả

nghiên cứu cho thấy sự không tương thích giữa tầm quan trọng của khóa học với các chuẩn của

NAATI và phương pháp lên lớp của giảng viên. Các giảng viên chưa trang bị cho sinh viên các kỹ

năng cần thiết của môn học. Tác giả đồng thời đề xuất một số hoạt động áp dụng trong lớp học khi

giảng dạy môn học này.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Giảng dạy môn Phiên dịch 1 tại khoa Ngoại ngữ: Đánh giá tổng quan và đề xuất hoạt động

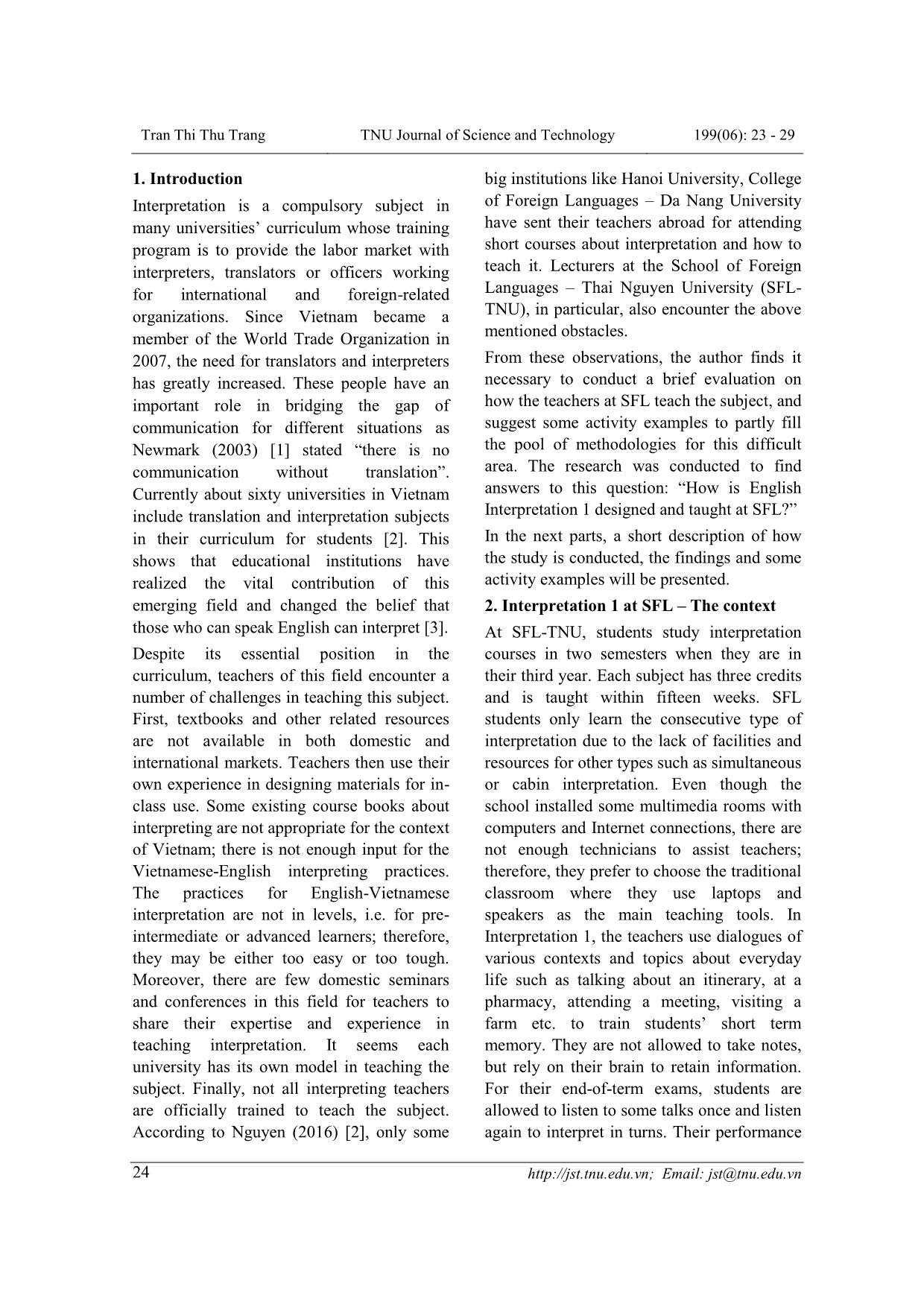

rate was 86.7%, which is an acceptable result for analysing and generalizing the research findings. 4. Results 4.1. A comparison between NAATI test formats and the course contents According to NAATI Information Booklet 2016 [5], the test for para-professional interpreters has three sections. Section 1 is about social and cultural awareness (5 marks). This section has questions to assess applicants’ understanding of how socio- cultural factors affect situations where an interpreter would be used. Section 2 (5 marks) tests the ethics of the profession to see if applicants understand the code of ethics and the professional conduct. The third section (90 marks) assesses applicant’s ability to be a bridge of communication for two people speaking different languages. There are two dialogues of 300 words with relatively simple information exchanged. Applicants interpret each segment of about 35 words with reasonable accuracy, style and register. The test for professional interpreters is more complicated. Applicants perform in two sections. In section 1, they have to interpret two dialogues (600 words in length, 60 words per segment); they then answer questions related to social and cultural awareness, which is followed by two questions related to the dialogues. After that, they see two texts of about 200 words each and translate them into a target language. In section 2, applicants do consecutive interpreting. They listen to some passages and interpret almost immediately. Sharing some commonalities with NAATI test format, the key contents of Interpretation 1 describe the code of ethics for interpreters, and emphasize concentration/memory. The latter one, however, is not practical as it is Tran Thi Thu Trang TNU Journal of Science and Technology 199(06): 23 - 29 Email: jst@tnu.edu.vn 26 merely about the major characteristics of short term memory; its role and its implications in interpreting process. There are no activities or strategies for improving short- term memory for students. For the progress tests and end-of-term exam, students come to the testing room, listen to two dialogues in both English and Vietnamese and interpret. From this analysis, it can be seen that despite the shared features of the course and what is considered standards by NAATI, Interpretation 1 should have included other important factors which NAATI looks into such as social and cultural awareness and the code of ethic. These should be explicitly presented in the tests or exams for students. 4.2. Students’ perceptions on the position of the subject One hundred per cent of the students agreed that Interpretation 1 (Oral translation 1) is a compulsory subject as it prepares them with necessary skills for their future jobs. Unlike other subjects which only centre around developing students’ language proficiency, this course trains them to have knowledge on a variety of topics, to master in skills related to their reactions, their short term memory beside improving their English listening and speaking abilities. 47 students (90.3%) indicated that three credits for this subject are enough and that three hours for in-class contact per week is appropriate. This maybe because they had to study about five to six other subjects, so this design for Interpretation will spare them some time to fulfil other courses. All of the students chose “disagree” when they were asked if they wanted to replace this subject by Translation courses where they study the written form of a text and write their translation output. Another noticeable finding is all of them were not introduced to NAATI during their study of the course. From these answers, we can see that the students were fully aware of the important role of this course and they supported SFL in allocating the course in its curriculum. This attitude may then affect their motivation and strategies in learning the subject. 4.3. Teachers’ teaching methodologies Table 1 shows the students’ responses to statements related to the teachers’ methodologies in teaching Interpretation 1. Table 1. Students’ evaluation on teachers’ methodologies Statements 1 2 3 1. The teacher introduced the course syllabus in details. 100% 2. The teacher gave clear instructions on how to use course book or reference materials for self-study. 58% 42% 3. The teacher provided materials for students to prepare for the next class. 100% 4. The teacher provided vocabulary according to topics/ categories. 96.1% 3.9% 5. The teacher used a variety of activities in teaching. 76.9% 23.1% 6. The teacher focused on training students’ short term memory. 88.5% 11.5 % 7. The teacher focused on training students’ reaction ability. 67.3% 7.8% 24.9% 8. The teacher divided segments for interpretation equally. 86.5% 13.5% 9. The teacher used a variety of topics for interpreting practices. 5.8% 94.2% 10. The teacher encouraged pair and group work in interpretation. 80.7% 19.3% The figures shown in this table indicate significant information about how students judged their teachers’ teaching methods. Firstly, the areas that were highly appreciated with almost 100% of the students were the detailed introduction of the course syllabus and the use of various topics for Tran Thi Thu Trang TNU Journal of Science and Technology 199(06): 23 - 29 Email: jst@tnu.edu.vn 27 students to practise. As a requirement from the board of managers, teachers at the beginning of a semester must provide a course syllabus so that students know what they are doing during the course. The topics as stated in the syllabus are all different for each week; therefore, when the teacher strictly followed the plan, students would be exposed to a number of familiar talks/dialogues. Apart from these two good aspects, the students had negative opinions towards several points. The first, and the most noticeable one was the materials provided for preparation prior to coming to the next class. 100% of the students claimed that the teachers should significantly increase this act. The fact is if they did not know what they would study next, they would be passive in looking for appropriate contents, knowledge related to culture and society for their interpretation. This may result in their unreadiness to participate in the lesson. Moreover, the teachers did not provide vocabulary according to themes/topics/ categories with 96.1% choosing number 1. The fact is if the students could have their own little glossary book, their revision of useful words/expressions would be more efficient. Regarding the key skills that the students were supposed to master, which are short-term memory and reaction ability, most of them pointed out that their teachers did not invest the right amount of time to instruct. It seems the students were not trained with techniques to retain information in their memory for a short span of time. Likewise, more than half (67.3%) of the participants stated that they needed more practices to improve their reaction. Real experience from interpreters around the world has proved that being able to deal with the existing situations while interpreting contributes greatly to their success or failures [6]. In terms of in-class activities, three fourths (80.7%) of the respondents claimed that their teachers mostly requested for individual work rather than pairs or groups. A similar number of students (76.9%) said that the class activities are monotonous. If the teachers only used “listen and repeat”, “listen and memorize”, “listen and interpret”, their teaching procedure would be repetitive and probably be demotivating to their learners. The investigation into the students’ evaluation on teachers’ methodologies has pointed out a number of problems in teaching the subject. Despite the significance of the subject, there is a mismatch between what is expected and what really happened. 4.4. Students’ attitudes towards the exam Screening the students’ summary of their attitudes towards the exam, some predicaments stood out. First, they did not know what topics they would interpret, so there was a high level of anxiety for the test takers. Furthermore, the topics of the tests were not the same as the ones they had studied before. Hence, when the audio was played, they were put in a shocking status even though difficult vocabulary was provided to them before listening. Another problem was the students had never seen their teachers analyse and mark their interpretation using a rubric of assessment; therefore, they didn’t know what to do. Overall, this subject was considered as a pressure for them. 4.5. Class observation The researcher’s notes revealed the same results found in the students’ questionnaire. In both of the observations, the teachers started their lesson by checking homework, then taught new vocabulary for the new interpretation. There were no lead-in or warm-up activities. They also followed a sequence in teaching: students listened for the first time – teachers paused the audio – students interpreted – teachers gave feedback. The class atmostphere was quiet and boring; few students volunteered to answer. Tran Thi Thu Trang TNU Journal of Science and Technology 199(06): 23 - 29 Email: jst@tnu.edu.vn 28 These observations have shown a correlation between what the students expressed in their questionnaire and what happened in class. 5. Class activity examples To address the issues of monotony, the lack of group work and to better instruct students to work on their own, the following activities can be applied by teachers of Interpretation 1. 5.1. News sharing News is a rich source for both in-class and after-class practices. Teachers can exploit this channel to set up a good habit for students. * Aims: this activity helps learners to - practise listening skills every week - update their understanding about social and cultural knowledge - expand their vocabulary in different fields - practise interpreting ability * Procedure: on week 1 of the course, teachers introduce some useful news websites for students such as: https://www.news inlevels.com/;https://breakingnewsenglish.co m/; https://tuoitrenews.vn/; https://edition. cnn.com/cnn10;https://www.sciencenewsforst udents.org/ etc. Students then choose a partner to work with and decide on one piece of news to read or listen to. After that, they both construct a summary of the news and interpret it into the target language. In class, teachers pick one pair of students to perform their preparation; one student reports the contents of what they read or listened to, the other interprets after two sentences by the first student. Teachers should remind their students that they may start with their topics of interests first, but after that they need to cover other topics to have a wider pool of useful vocabulary. 5.2. Running interpretation The American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found positive associations between classroom-based physical activity and indicators of cognitive skills and attitudes, academic behavior, and academic achievement (McCaughey, K. 2018) [7]. This is to say that teachers should involve physical movement for their students while learning. * Aims: this activity helps learners to: - move and learn at the same time - interpret in a fun and competitive way - collaborate as a group. * Procedure: After preparing ideas and necessary knowledge for the output, students stand in groups on one side of the class. Teachers write the word “Finish” on the board. Teachers then play the audio and pause after each segment of two to three sentences. Groups discuss their interpretation and put up their hand to win the turn to translate. Each correct translation will give the group a chance to send one member to the Finish area. The group with all members at the Finish position will win. 5.3. Interpreting with a phone Most students nowadays use smartphones, and teachers can take advantage of this device to teach. * Aims: this activity helps students to - collaborate in groups - practise their interpreting skills * Procedure: students are divided into groups of three or four. Teachers play the audio and pause after each segment, groups discuss their interpretation. They then take turn recording their translation on their mobile phones. Teachers may play their recordings through a speaker when they finish. 6. Conclusion The research findings have exposed some uncorrelations between the essential position of the course and the reality of teaching this subject. Despite the fact that Interpretation courses are the core of SFL training programs, the teachers responsible for this Tran Thi Thu Trang TNU Journal of Science and Technology 199(06): 23 - 29 Email: jst@tnu.edu.vn 29 subject encountered a lot of challenges. First, they had no coursebook to officially use in class. Second, maybe because no one of them was trained to be interpreters or had real experience of working in this field, their teaching methods did not meet the need of their students. SFL should really look into these problems and have policies/plans for its teachers to improve their knowledge and methods of teaching this subject. REFERENCES [1]. Newmark, P., “No Global Communication without Translation” in Anderman, Gunilla & Rogers, Margaret (eds.), Translation Today: Trends and Perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd, 55-67, 2003. [2]. Nguyễn Thị Như Ngọc, “Khảo sát thực trạng hoạt động đào tạo biên phiên dịch tiếng Anh tại một số trường đại học tại Việt Nam hiện nay”, Kỷ yếu hội thảo giảng dạy biên phiên dịch, Đại học KHXH&NV thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, tr.3-20, 2016. [3]. Nguyễn Quang Nhật, “Giảng dạy môn phiên dịch trong bối cảnh hội nhập – dạy học theo phương pháp tiếp cận năng lực”, Kỷ yếu hội thảo giảng dạy biên phiên dịch, Đại học KHXH&NV thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, tr.94 – 100, 2016. [4]. Gravestock, P. & Gregor-Greenleaf, E., “Student Course Evaluations: Research, Models and Trends”, Toronto: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, 2008. [5]. Accreditation by testing – Information booklet, NAATI, 10-2015. Retrieved from https://www.naati.com.au/media/1451/accredi tation_by_testing_information_booklet.pdf on March 10, 2019. [6]. Camellia, P., The interpreter’s role”,. Translation Journal, V6, No. 2, 95-110, 2014. [7]. McCaughey, K., “Skim, scan, and run.” English Teaching Forum v56 No.1, 45-52, 2018.

File đính kèm:

giang_day_mon_phien_dich_1_tai_khoa_ngoai_ngu_danh_gia_tong.pdf

giang_day_mon_phien_dich_1_tai_khoa_ngoai_ngu_danh_gia_tong.pdf