Design for aesthetics: Interactions of design variables and aesthetic properties

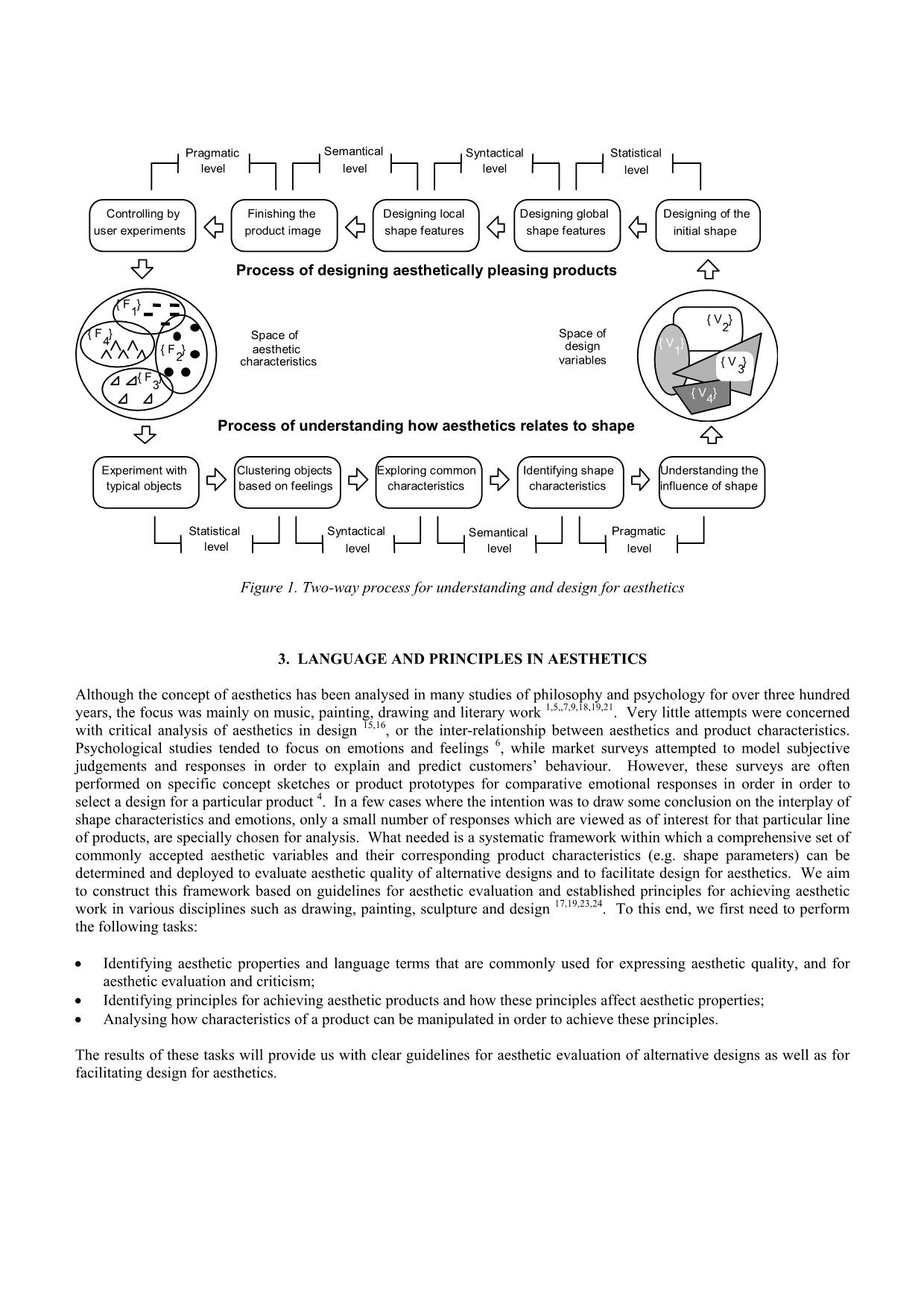

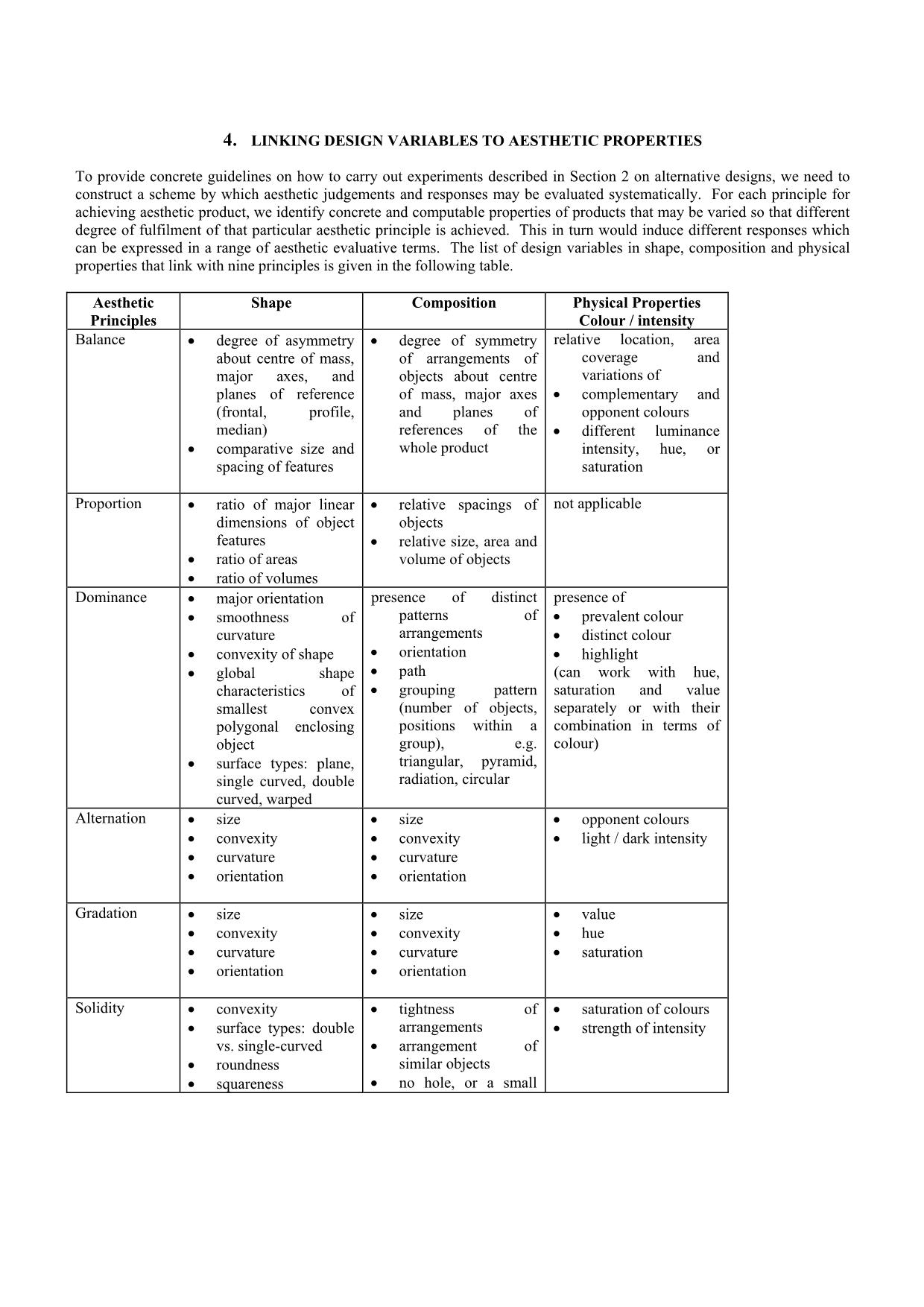

ABSTRACT This paper proposed a systematic approach for exploring the interactions of aesthetic properties and design variables, by integrating knowledge from other fields such as philosophy, psychology and arts. Commonly-Accepted aesthetic properties and language terms used for evaluation and criticism are first discussed and a common set of nine principles for achieving aesthetic products in a number of creative disciplines is identified. We then analyse the way these principles influence product characteristics and extract concrete and computable properties of products that may be varied to induce different aesthetic judgements and responses

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Bạn đang xem tài liệu "Design for aesthetics: Interactions of design variables and aesthetic properties", để tải tài liệu gốc về máy hãy click vào nút Download ở trên

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Design for aesthetics: Interactions of design variables and aesthetic properties

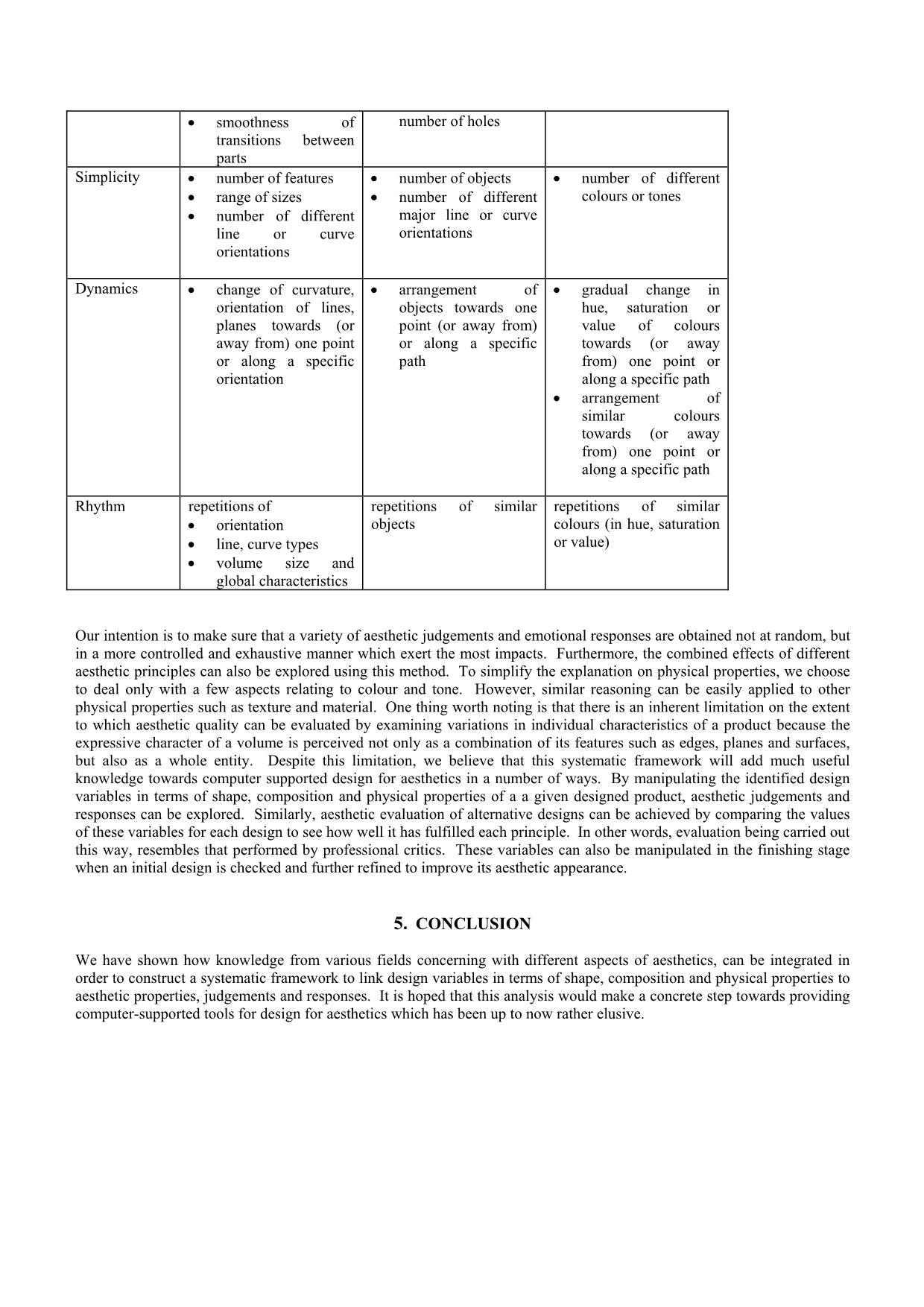

for automation was by Stiny & Gips 20 who provided a general framework for constructing computer algorithms for aesthetic criticism and design. These algorithms did not attempt to give a complete specification for evaluating or creating a specific art work, but offered a common structure to investigate important issues in aesthetics in a unified and coherent manner. However, apart from some simple examples which involved shape grammar and coloring rules for two-dimensional pictures, these algorithms still only gave very high- level details and are not suitable for our purposes. 3.2. Basic Principles for Producing Aesthetic Products A survey of literature in various disciplines such as drawing, painting, sculpture, industrial design and graphic design has revealed that there is much overlap in individual sets of basic principles for producing aesthetic products. Minor differences in meaning of a certain principle or omission of certain principles tend to be due only to the nature of media or material from which products are constructed. Furthermore, these principles when applied to products, provoke a diverse range of emotion responses which may be expressed in evaluative aesthetic terms mentioned in the previous Section. By judicious examination of such principles from these fields, we have come up with a list of nine principles that we believe, is sufficiently comprehensive to be used as a base for analysing the interactions between aesthetic characteristics and product characteristics. We now discuss the implication of each principle and how it relates to shape, composition and physical properties. Balance This principle is concerned with the effect of visual equilibrium. A design is monotonous and unexciting if evenness is strongly perceived in every characteristics, hence symmetric is generally avoided. On the other hand, asymmetry in shape features, colour, tone, size or arrangements of parts can give a design a more distinct characteristics. A balanced composition which, according to Ruskin, “puts several things together so as to make one thing of them”, hence also creates unity. A closely related principle to balance is that of harmony where pleasant effects are created by grouping objects with characteristics which are in accordance with each other, e.g. complementary shapes and colours. Proportion Although the principle of proportion is closely related to that of balance, it tends to be dealt with separately to refer specifically to spatial balance. There are three types of proportions: linear, areal and volumetric. Linear proportion refers to the relation between the dimensions (e.g. length, width) of a single object (or feature), or between a linear dimension of one object (or feature) and that of another. A number of standard good proportion exist (e.g. the golden section). Areal and volumetric refers to similar relations in the areas and volumes of objects (or features). Within this context, distinct objects (or features) may be viewed as being separated by shape, colour, texture or material. Dominance / Principality This principle expresses that the unity of a design can be achieved by allowing one feature to dominate the rest. The dominant feature may be a distinct shape, colour, material or a distinct arrangement that mark it out from other features. It also creates a focal point which induces the effect of leading the eye towards it. Alternation / Interchange / Contrast The combination of things of significantly different characteristics create more impact, for example, light against dark, positive against negative shapes, smooth against sharp curvature, vertical against horizontal directions. However, great contrast in tone may prevent full appreciation of colour, by given an illusion of a different hue. For example, a colour would appear darker if surrounded by a much lighter colour. Gradation / Continuity Changes in a gradual or orderly fashion can add interest yet calm feeling, e.g. subtle variation in colours, shapes or the way features or object components are arranged. On the other hand, abruptness or discontinuity produces striking effects and unsettling feeling. Solidity / Structural Coherence The sensation of solidity can be created by fullness or robust characteristics such as round objects of heavy material and solid colours. Double curved surfaces generally give an impression of more fullness than a single curved surface. Abrupt transitions between parts tend to give a feel of being breakable or fragile. Visual power which suggests stability and strength, can also be increased by combining several elements of similar characteristics into one whole mass, e.g. a tight arrangement of sharp objects along a parallel direction. Simplicity Over-crowded features or over-precisely arrangement of objects may lose spontaneity and dilute focus. Dynamics Boldness in terms of energy and tension may be suggested by certain characteristics such as radial directions, gravitational pulling forces and outwardly thrusting forces. A sense of movement may also be induced by a definite orientation or path, e.g. a spiral composition around an axis. Rhythm The eye recognises a repeated form, colour, intensity or tone very quickly, hence repetitions can provoke interesting effects. However, some variations are needed to prevent monotony. A sensation of rhythm or visual kinetics can be created by the repetition of objects of similar characteristics, e.g. a group of cylinders of different sizes along a slanted and parallel direction induces a sensation of undulating rhythm. 4. LINKING DESIGN VARIABLES TO AESTHETIC PROPERTIES To provide concrete guidelines on how to carry out experiments described in Section 2 on alternative designs, we need to construct a scheme by which aesthetic judgements and responses may be evaluated systematically. For each principle for achieving aesthetic product, we identify concrete and computable properties of products that may be varied so that different degree of fulfilment of that particular aesthetic principle is achieved. This in turn would induce different responses which can be expressed in a range of aesthetic evaluative terms. The list of design variables in shape, composition and physical properties that link with nine principles is given in the following table. Aesthetic Principles Shape Composition Physical Properties Colour / intensity Balance • degree of asymmetry about centre of mass, major axes, and planes of reference (frontal, profile, median) • comparative size and spacing of features • degree of symmetry of arrangements of objects about centre of mass, major axes and planes of references of the whole product relative location, area coverage and variations of • complementary and opponent colours • different luminance intensity, hue, or saturation Proportion • ratio of major linear dimensions of object features • ratio of areas • ratio of volumes • relative spacings of objects • relative size, area and volume of objects not applicable Dominance • major orientation • smoothness of curvature • convexity of shape • global shape characteristics of smallest convex polygonal enclosing object • surface types: plane, single curved, double curved, warped presence of distinct patterns of arrangements • orientation • path • grouping pattern (number of objects, positions within a group), e.g. triangular, pyramid, radiation, circular presence of • prevalent colour • distinct colour • highlight (can work with hue, saturation and value separately or with their combination in terms of colour) Alternation • size • convexity • curvature • orientation • size • convexity • curvature • orientation • opponent colours • light / dark intensity Gradation • size • convexity • curvature • orientation • size • convexity • curvature • orientation • value • hue • saturation Solidity • convexity • surface types: double vs. single-curved • roundness • squareness • tightness of arrangements • arrangement of similar objects • no hole, or a small • saturation of colours • strength of intensity • smoothness of transitions between parts number of holes Simplicity • number of features • range of sizes • number of different line or curve orientations • number of objects • number of different major line or curve orientations • number of different colours or tones Dynamics • change of curvature, orientation of lines, planes towards (or away from) one point or along a specific orientation • arrangement of objects towards one point (or away from) or along a specific path • gradual change in hue, saturation or value of colours towards (or away from) one point or along a specific path • arrangement of similar colours towards (or away from) one point or along a specific path Rhythm repetitions of • orientation • line, curve types • volume size and global characteristics repetitions of similar objects repetitions of similar colours (in hue, saturation or value) Our intention is to make sure that a variety of aesthetic judgements and emotional responses are obtained not at random, but in a more controlled and exhaustive manner which exert the most impacts. Furthermore, the combined effects of different aesthetic principles can also be explored using this method. To simplify the explanation on physical properties, we choose to deal only with a few aspects relating to colour and tone. However, similar reasoning can be easily applied to other physical properties such as texture and material. One thing worth noting is that there is an inherent limitation on the extent to which aesthetic quality can be evaluated by examining variations in individual characteristics of a product because the expressive character of a volume is perceived not only as a combination of its features such as edges, planes and surfaces, but also as a whole entity. Despite this limitation, we believe that this systematic framework will add much useful knowledge towards computer supported design for aesthetics in a number of ways. By manipulating the identified design variables in terms of shape, composition and physical properties of a a given designed product, aesthetic judgements and responses can be explored. Similarly, aesthetic evaluation of alternative designs can be achieved by comparing the values of these variables for each design to see how well it has fulfilled each principle. In other words, evaluation being carried out this way, resembles that performed by professional critics. These variables can also be manipulated in the finishing stage when an initial design is checked and further refined to improve its aesthetic appearance. 5. CONCLUSION We have shown how knowledge from various fields concerning with different aspects of aesthetics, can be integrated in order to construct a systematic framework to link design variables in terms of shape, composition and physical properties to aesthetic properties, judgements and responses. It is hoped that this analysis would make a concrete step towards providing computer-supported tools for design for aesthetics which has been up to now rather elusive. ACKNOWLEGEMENT The author would like to thank the Integrated Concept Advancement (ICA) group of the Sub-Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, FDEP, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands, for many inspiring discussions during her visit. REFERENCES 1. Beardsley M.C, “Aesthetics”, Hartcourt, Brace & World, New York, 1958. 2. Breemen E.J.J. van, Knoop W.G., Horváth I., Vergeest, J.S.M. and Pham B. (1998), “Developing a methodology for design for aesthetics based on analogy of communication”, Proceedings of 1998 ASME DTM Conference, September 1998, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. 3. Chen, K., Owen, C.L, “Form Language and Style Description”, Design Studies, vol.18, nr.3, pp.249-274, 1997. 4. Desmet, P.M.A., Tax, S.J.E.T., “Designing a Mobile Telecommunication Device with an Emotional Surplus Value: a Case Study”, to appear in Design Studies, 1998 5. Dickie G., “Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis”, Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London, 1974. 6. Frijda, N.H., “The Emotions, Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction”, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1986. 7. Gatta K., Lange G. and Lyons M., “Foundations of Graphic Design”, Davis Publications, Worcester, Massachusetts, 1991. 8. Goldman “Aesthetic Value”, Westview Press, Colorado, 1995. 9. Hine T., “The Total Pakage: The Evolution and Secret Meanings of Boxes, Bottles, Cans, and Tubes”, Little , Brown and Company, NY, 1995. 10. Kant I., Critique of Judgement (Kritik der Urteilskraft), 1790. 11. Knoop W.G., Breemen E.J.J. van, Horváth I., Vergeest, J.S.M. and Pham B., “Towards Computer Supported Design for Aesthetics”, 31st ASATA - International Symposium on Automotive Technology and Automation, Dusseldorf, Germany, 2-5 June 1998. 12. Meadow, C. T., Yuan, W., "Measuring the Impact of Information: Defining the Concepts", Information Processing and Management, Vol. 33, No. 6, pp. 697-714, 1997. 13. Palmer, J., Dodson, M., (1996), "Design and Aesthetics: A Reader", Routledge Publisher, London. 14. Pham, B., “Integration of aesthetic intents to CAD systems” in: Proceedings of the 1996 ASME Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers in Engineering Comference, August 18-22, Irvine , California, USA, Published on CD-ROM, Papernr. 96-DETC/CIE-1333, 1996. 15. Pye D., “The Nature and Aesthetics of Design”, The Herbert Press, UK, 1995. 16. Reich, Y., “A Model of Aesthetic Judgment in Design”, Artificial Intelligence in Engineering, vol.8, no.2, pp.141- 153, 1993. 17. Rogers L.R., “Sculpture - The Appreciation of the Arts”, Oxford University Press, London, 1969. 18. Ruskin, J., “The Elements of Drawing”, Rover Publications, New York, 1971 (first published 1857). 19. de Sausmarez M., “Basic Design: The Dynamics of Visual Form”, Herbert Pres. Ltd London, 1987. 20. Stiny G.N. and Gips, “Algorithmic Aesthetics: Computer Models for Criticism and Design in the Arts”, University of California Press, Berkley, LA, 1978. 21. Tolstoy L., “What is Art?”, Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, 1896, reprinted 1960. 22. Tovey, M., “Styling and design: intuition and analysis in industrial design” in Design Studies vol.18, nr.1, pp. 5-32, Elsevier, London, 1997. 23. Van Hasselt T. and Wagner J., “Building Better Paintings”, Australian Artist Magazine, N164, pp49-53, 1997. 24. Willcox D., “Wood Design”, Watson-Guptill Publications, N.Y, 1972.

File đính kèm:

design_for_aesthetics_interactions_of_design_variables_and_a.pdf

design_for_aesthetics_interactions_of_design_variables_and_a.pdf