A longitudinal study of audit quality differences among independent auditors

Abstract

Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to investigate the differences of audit quality of financial statements

among auditors, including Big 4 and non-Big 4 auditors.

Design/methodology/approach – By employing cross-sectional analysis of compliance (a proxy of audit

quality) of goodwill impairment testing of listed firms in the context of Hong Kong, the variation of audit

quality of financial statements of auditees has been shown.

Findings – Audit quality of Big 4 auditors is viewed to be higher than that of non-Big 4 audit firms and the

homogeneity of audit quality among Big 4 auditors is not long accepted, but variation.

Practical implications – Even though unqualified opinions have been given on the auditors’ reports, the

quality of financial statements audit is a skeptical issue because of the high level of non-compliance of

goodwill impairment testing under International Financial Reporting Standards.

Originality/value – This study does emphasize the higher audit quality of financial statements of Big

4 auditors than that of non-Big 4 auditors and stresses the variation of audit quality among Big 4 auditors.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: A longitudinal study of audit quality differences among independent auditors

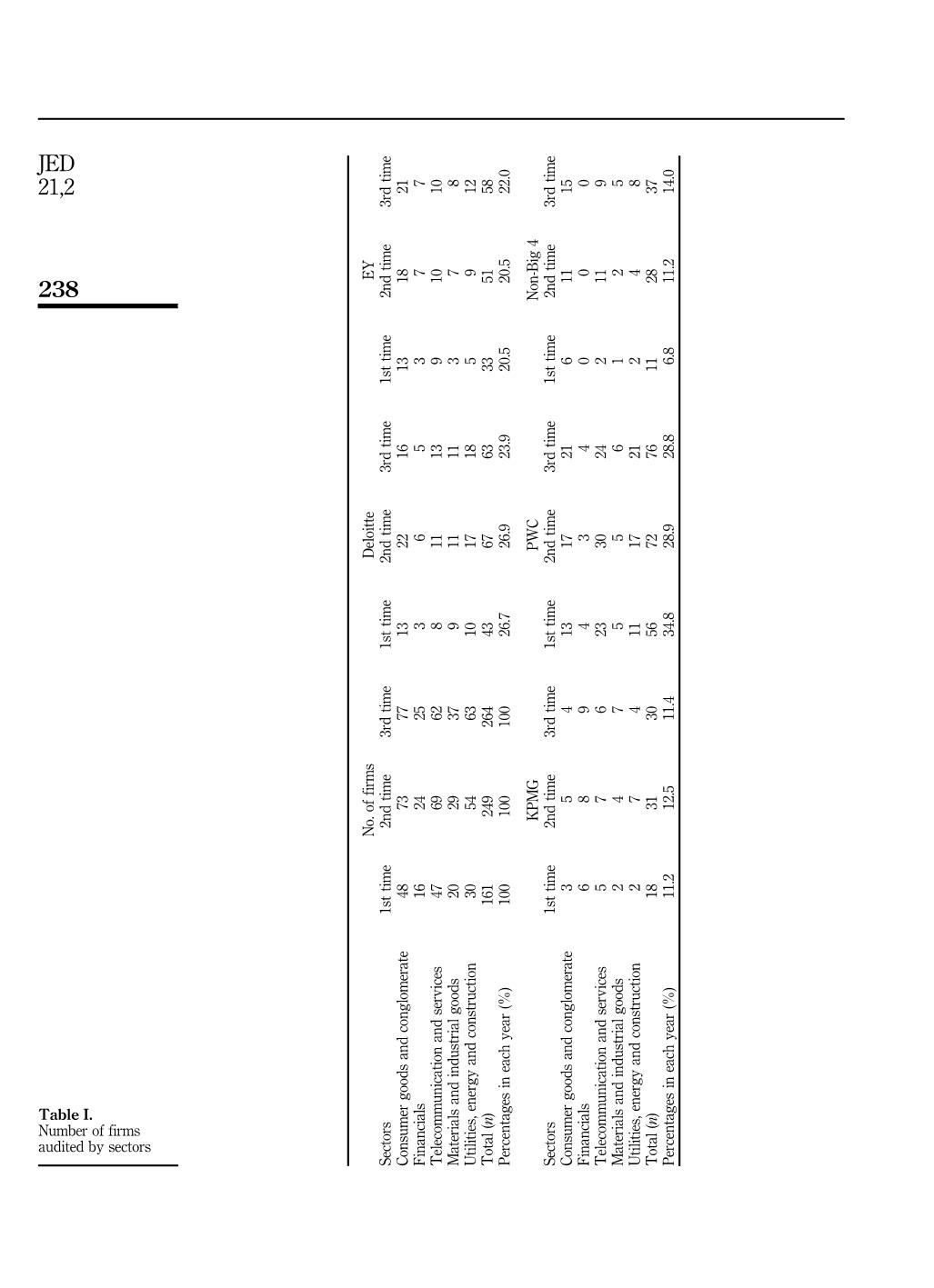

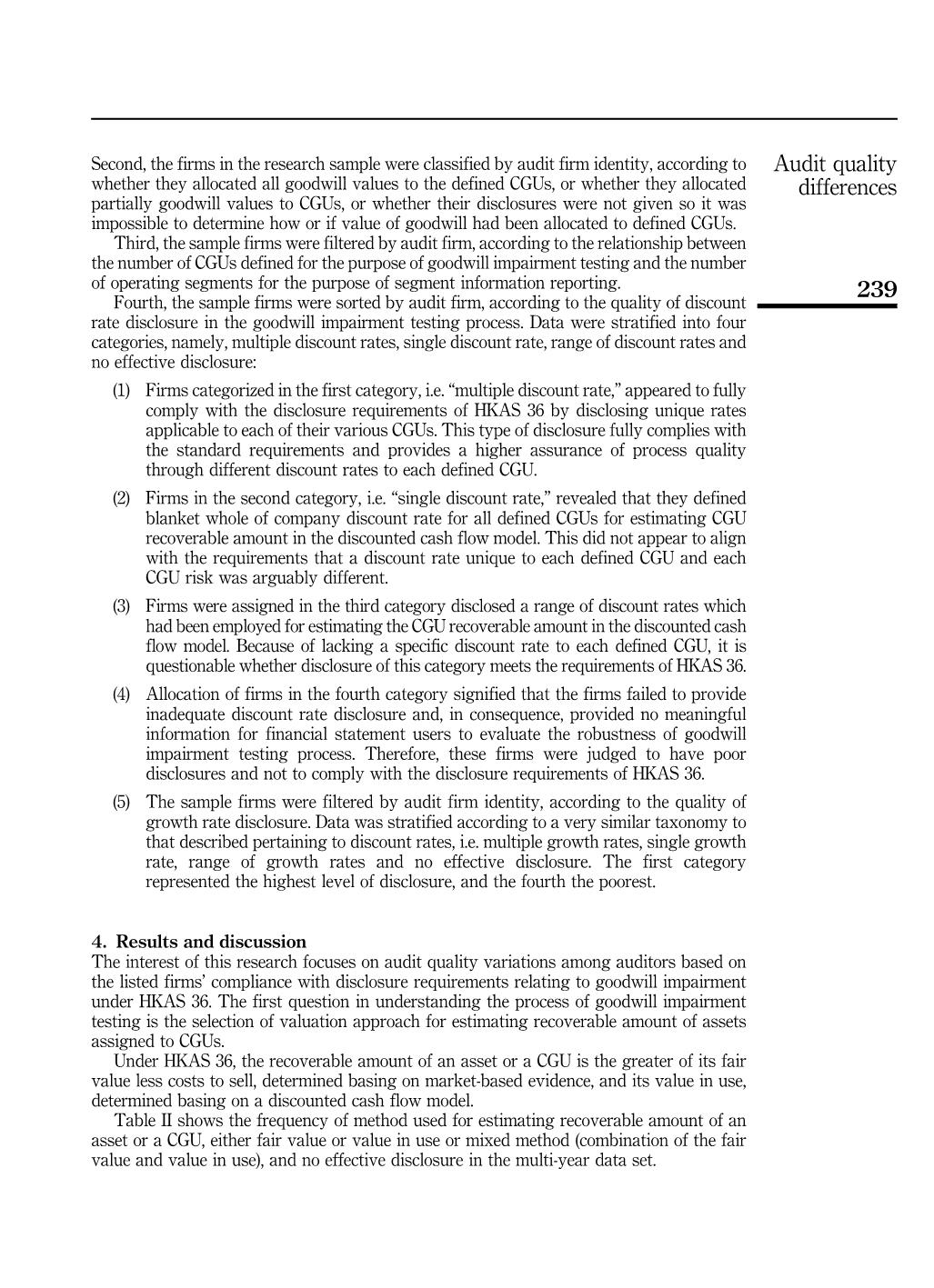

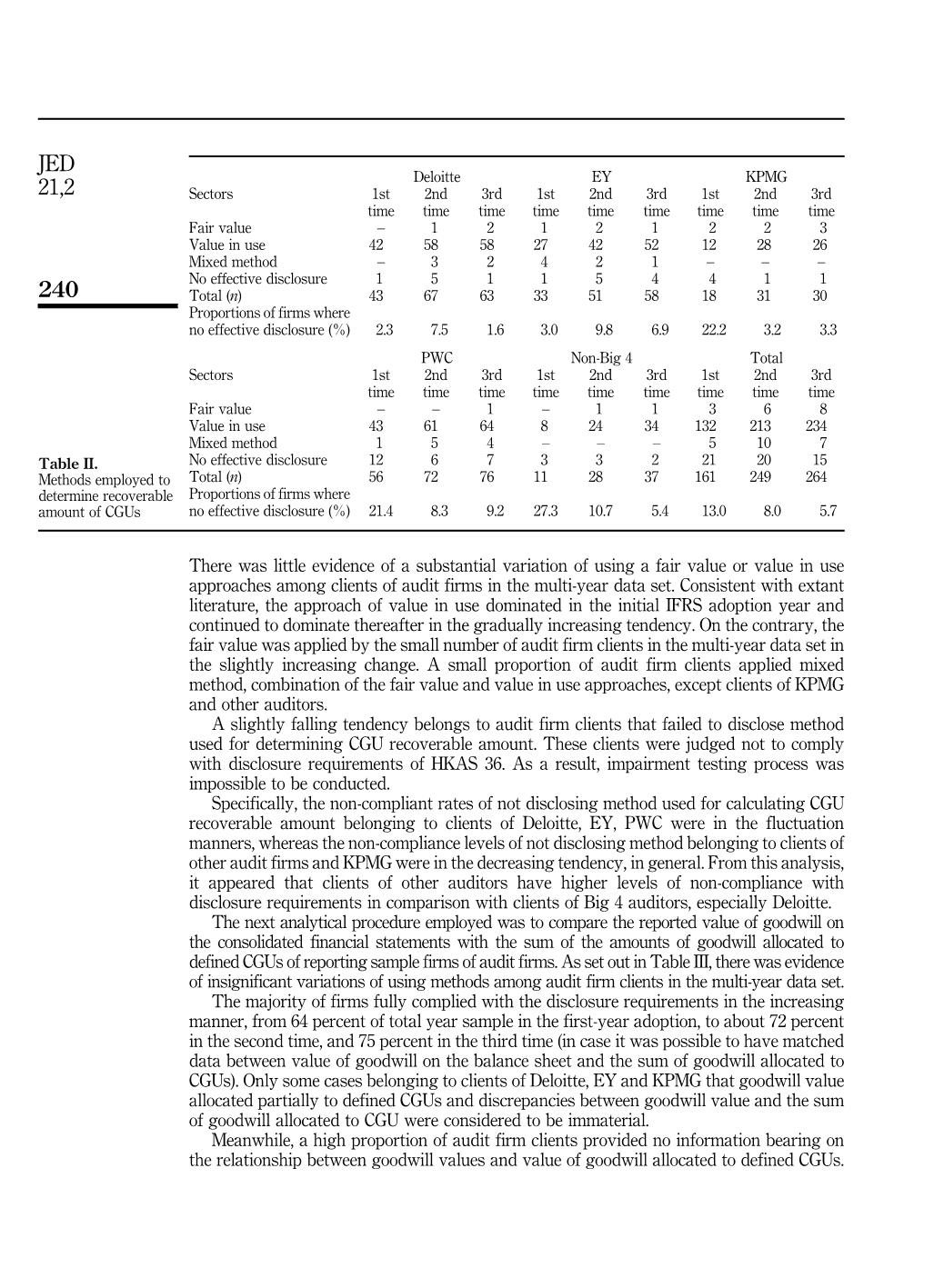

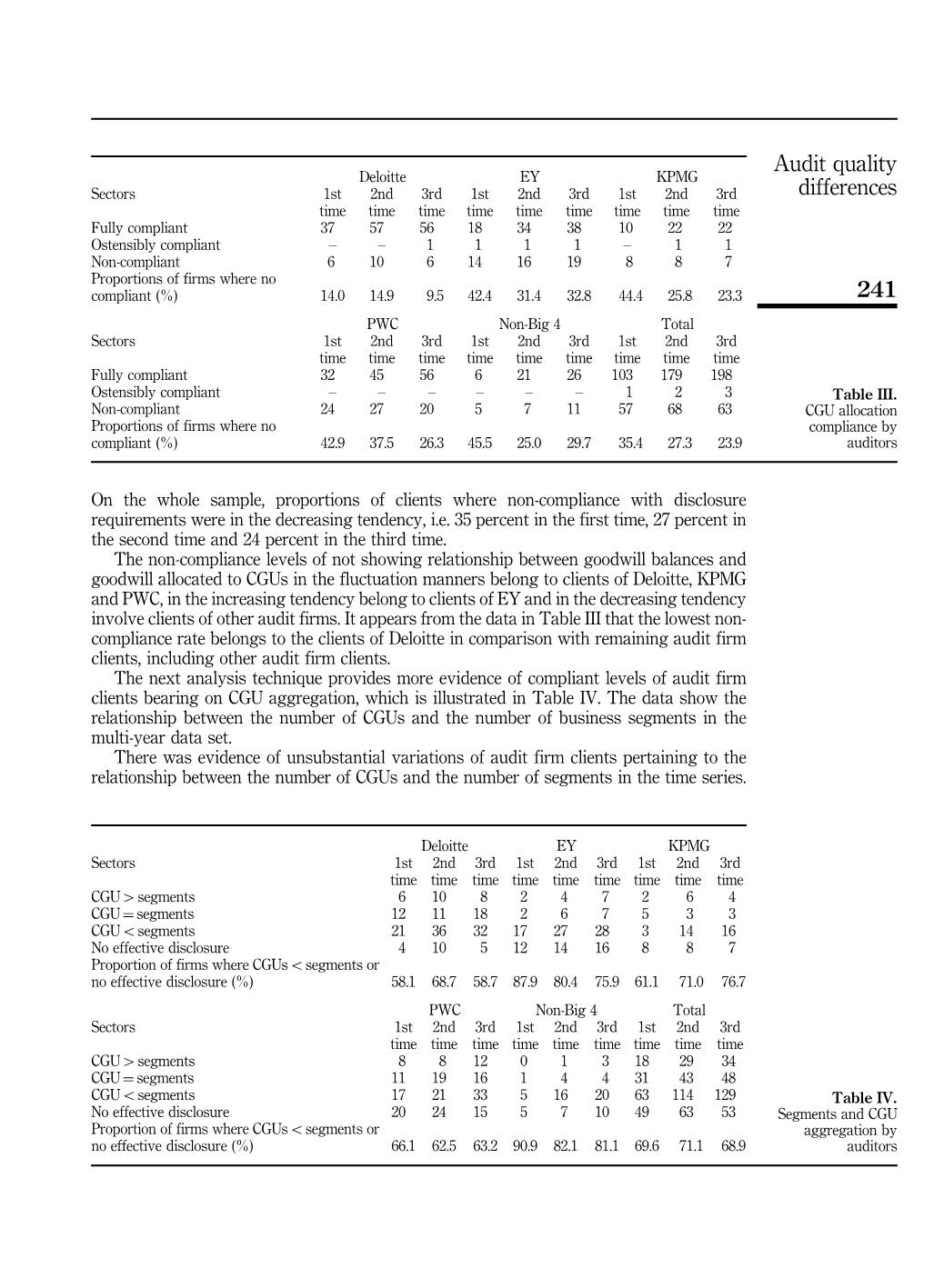

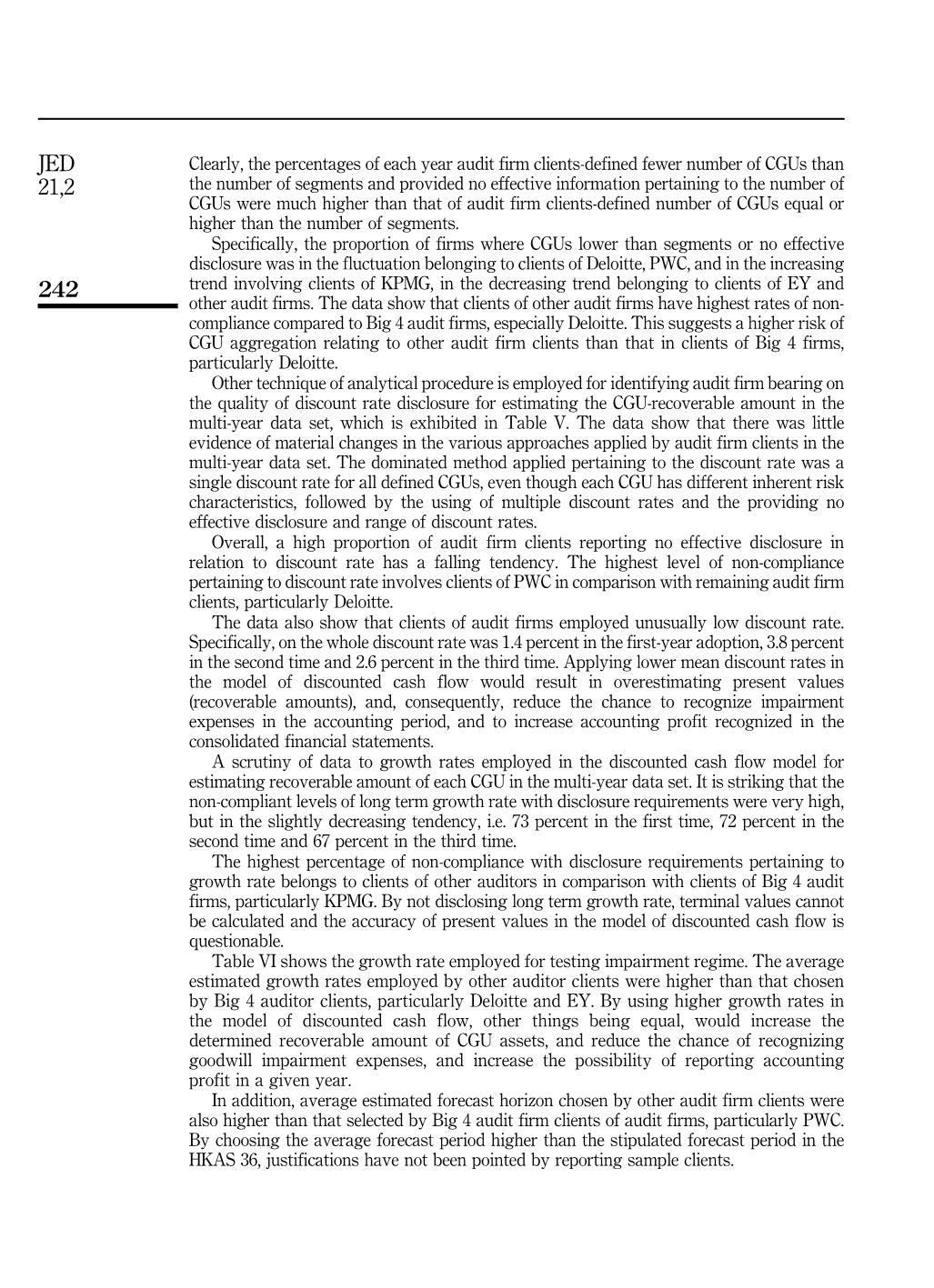

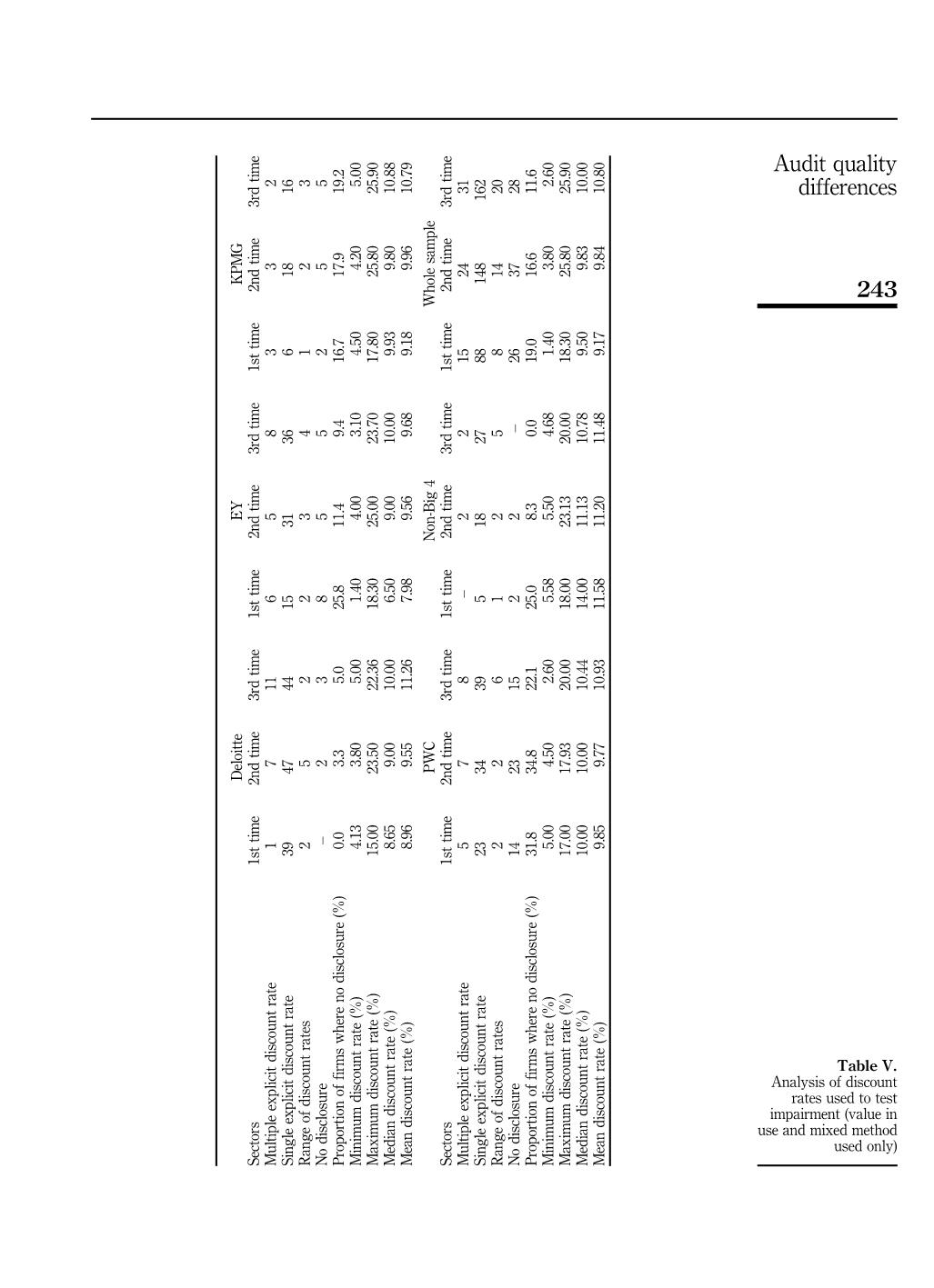

ts 8 8 12 0 1 3 18 29 34 CGU¼ segments 11 19 16 1 4 4 31 43 48 CGUosegments 17 21 33 5 16 20 63 114 129 No effective disclosure 20 24 15 5 7 10 49 63 53 Proportion of firms where CGUsosegments or no effective disclosure (%) 66.1 62.5 63.2 90.9 82.1 81.1 69.6 71.1 68.9 Table IV. Segments and CGU aggregation by auditors 241 Audit quality differences Clearly, the percentages of each year audit firm clients-defined fewer number of CGUs than the number of segments and provided no effective information pertaining to the number of CGUs were much higher than that of audit firm clients-defined number of CGUs equal or higher than the number of segments. Specifically, the proportion of firms where CGUs lower than segments or no effective disclosure was in the fluctuation belonging to clients of Deloitte, PWC, and in the increasing trend involving clients of KPMG, in the decreasing trend belonging to clients of EY and other audit firms. The data show that clients of other audit firms have highest rates of non- compliance compared to Big 4 audit firms, especially Deloitte. This suggests a higher risk of CGU aggregation relating to other audit firm clients than that in clients of Big 4 firms, particularly Deloitte. Other technique of analytical procedure is employed for identifying audit firm bearing on the quality of discount rate disclosure for estimating the CGU-recoverable amount in the multi-year data set, which is exhibited in Table V. The data show that there was little evidence of material changes in the various approaches applied by audit firm clients in the multi-year data set. The dominated method applied pertaining to the discount rate was a single discount rate for all defined CGUs, even though each CGU has different inherent risk characteristics, followed by the using of multiple discount rates and the providing no effective disclosure and range of discount rates. Overall, a high proportion of audit firm clients reporting no effective disclosure in relation to discount rate has a falling tendency. The highest level of non-compliance pertaining to discount rate involves clients of PWC in comparison with remaining audit firm clients, particularly Deloitte. The data also show that clients of audit firms employed unusually low discount rate. Specifically, on the whole discount rate was 1.4 percent in the first-year adoption, 3.8 percent in the second time and 2.6 percent in the third time. Applying lower mean discount rates in the model of discounted cash flow would result in overestimating present values (recoverable amounts), and, consequently, reduce the chance to recognize impairment expenses in the accounting period, and to increase accounting profit recognized in the consolidated financial statements. A scrutiny of data to growth rates employed in the discounted cash flow model for estimating recoverable amount of each CGU in the multi-year data set. It is striking that the non-compliant levels of long term growth rate with disclosure requirements were very high, but in the slightly decreasing tendency, i.e. 73 percent in the first time, 72 percent in the second time and 67 percent in the third time. The highest percentage of non-compliance with disclosure requirements pertaining to growth rate belongs to clients of other auditors in comparison with clients of Big 4 audit firms, particularly KPMG. By not disclosing long term growth rate, terminal values cannot be calculated and the accuracy of present values in the model of discounted cash flow is questionable. Table VI shows the growth rate employed for testing impairment regime. The average estimated growth rates employed by other auditor clients were higher than that chosen by Big 4 auditor clients, particularly Deloitte and EY. By using higher growth rates in the model of discounted cash flow, other things being equal, would increase the determined recoverable amount of CGU assets, and reduce the chance of recognizing goodwill impairment expenses, and increase the possibility of reporting accounting profit in a given year. In addition, average estimated forecast horizon chosen by other audit firm clients were also higher than that selected by Big 4 audit firm clients of audit firms, particularly PWC. By choosing the average forecast period higher than the stipulated forecast period in the HKAS 36, justifications have not been pointed by reporting sample clients. 242 JED 21,2 D el oi tt e E Y K PM G Se ct or s 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e M ul tip le ex pl ic it di sc ou nt ra te 1 7 11 6 5 8 3 3 2 Si ng le ex pl ic it di sc ou nt ra te 39 47 44 15 31 36 6 18 16 R an ge of di sc ou nt ra te s 2 5 2 2 3 4 1 2 3 N o di sc lo su re – 2 3 8 5 5 2 5 5 Pr op or tio n of fir m s w he re no di sc lo su re (% ) 0. 0 3. 3 5. 0 25 .8 11 .4 9. 4 16 .7 17 .9 19 .2 M in im um di sc ou nt ra te (% ) 4. 13 3. 80 5. 00 1. 40 4. 00 3. 10 4. 50 4. 20 5. 00 M ax im um di sc ou nt ra te (% ) 15 .0 0 23 .5 0 22 .3 6 18 .3 0 25 .0 0 23 .7 0 17 .8 0 25 .8 0 25 .9 0 M ed ia n di sc ou nt ra te (% ) 8. 65 9. 00 10 .0 0 6. 50 9. 00 10 .0 0 9. 93 9. 80 10 .8 8 M ea n di sc ou nt ra te (% ) 8. 96 9. 55 11 .2 6 7. 98 9. 56 9. 68 9. 18 9. 96 10 .7 9 PW C N on -B ig 4 W ho le sa m pl e Se ct or s 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e M ul tip le ex pl ic it di sc ou nt ra te 5 7 8 – 2 2 15 24 31 Si ng le ex pl ic it di sc ou nt ra te 23 34 39 5 18 27 88 14 8 16 2 R an ge of di sc ou nt ra te s 2 2 6 1 2 5 8 14 20 N o di sc lo su re 14 23 15 2 2 – 26 37 28 Pr op or tio n of fir m s w he re no di sc lo su re (% ) 31 .8 34 .8 22 .1 25 .0 8. 3 0. 0 19 .0 16 .6 11 .6 M in im um di sc ou nt ra te (% ) 5. 00 4. 50 2. 60 5. 58 5. 50 4. 68 1. 40 3. 80 2. 60 M ax im um di sc ou nt ra te (% ) 17 .0 0 17 .9 3 20 .0 0 18 .0 0 23 .1 3 20 .0 0 18 .3 0 25 .8 0 25 .9 0 M ed ia n di sc ou nt ra te (% ) 10 .0 0 10 .0 0 10 .4 4 14 .0 0 11 .1 3 10 .7 8 9. 50 9. 83 10 .0 0 M ea n di sc ou nt ra te (% ) 9. 85 9. 77 10 .9 3 11 .5 8 11 .2 0 11 .4 8 9. 17 9. 84 10 .8 0 Table V. Analysis of discount rates used to test impairment (value in use and mixed method used only) 243 Audit quality differences D el oi tt e E Y K PM G Se ct or s 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e M ul tip le ex pl ic it gr ow th ra te 1 1 5 3 3 4 2 3 2 Si ng le ex pl ic it gr ow th ra te 5 10 11 8 10 16 6 8 7 R an ge of gr ow th ra te s – 1 2 – 1 – – 1 – N o di sc lo su re 36 49 42 20 30 33 4 16 17 Pr op or tio n of fir m s w he re no di sc lo su re (% ) 85 .7 80 .3 70 .0 64 .5 68 .2 62 .3 33 .3 57 .1 65 .4 M in im um gr ow th ra te (% ) 0. 00 − 1. 00 0. 00 0. 00 0. 00 0. 00 0. 00 0. 00 0. 50 M ax im um gr ow th ra te (% ) 6. 90 9. 00 26 .7 6 10 .0 0 14 .0 0 12 .0 0 6. 54 6. 54 8. 00 M ed ia n gr ow th ra te (% ) 0. 00 1. 50 2. 75 0. 00 1. 25 3. 90 4. 65 3. 03 5. 00 M ea n gr ow th ra te (% ) 1. 88 2. 54 3. 40 1. 85 3. 11 3. 29 3. 52 3. 32 4. 94 PW C N on -B ig 4 W ho le sa m pl e Se ct or s 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e 1s t tim e 2n d tim e 3r d tim e M ul tip le ex pl ic it gr ow th ra te 3 6 3 – – 1 9 13 15 Si ng le ex pl ic it gr ow th ra te 8 9 14 – 5 8 27 42 56 R an ge of gr ow th ra te s 1 4 5 – 1 1 1 8 8 N o di sc lo su re 32 47 46 8 18 24 10 0 16 0 16 2 Pr op or tio n of fir m s w he re no di sc lo su re (% ) 72 .7 71 .2 67 .6 10 0. 0 75 .0 70 .6 73 .0 71 .7 67 .2 M in im um gr ow th ra te (% ) 0. 00 0. 00 0. 00 n/ d 2. 00 0. 00 0. 00 − 1. 00 0. 00 M ax im um gr ow th ra te (% ) 13 .0 0 20 .0 0 15 .6 0 n/ d 7. 00 21 .0 0 13 .0 0 20 .0 0 26 .7 6 M ed ia n gr ow th ra te (% ) 3. 70 2. 00 3. 40 n/ d 4. 00 3. 00 3. 00 2. 88 3. 40 M ea n gr ow th ra te (% ) 4. 61 3. 47 3. 99 n/ d 4. 30 6. 13 3. 11 3. 25 3. 99 Table VI. Analysis of growth rates used to test impairment (value in use and mixed method used only) 244 JED 21,2 5. Conclusion This research is conducted for finding evidence which might reveal variations in audit quality among auditors (Deloitte, EY, KPMG, PWC and other audit firms) in the multi-year data set. The methodology applied in this study focused on the nature and quality of disclosures in relation to the goodwill impairment testing process under HKAS 36. Basing on accumulated evidence obtained from the sample of listed firms in Hong Kong in three years after HKFRS adoption, including HKAS 36. By testing the basic disclosure requirements pertaining to goodwill impairment such as method used, CGU aggregation and specific disclosure requirements in relation to related assumptions such as variables of discount rates and growth rates in the discounted cash flow model, the research found that there was systematically non-compliant levels and poor disclosure quality pertaining to goodwill impairment among clients of auditors in the multi-year data set after HKFRS adoption. Taking an overview of the whole sample, variations of non-compliant rates with disclosure requirements pertaining to goodwill impairment was small and in the slightly decreasing tendency in the time series. Taking specific audit firm clients in each year sample, the highest rates of non-compliance with disclosure requirements pertaining to goodwill impairment stick to clients of other audit firms in comparison with clients of Big 4 auditors. Out of Big 4 auditors, clients of Deloitte were judged, on the whole, to be the best practice disclosure bearing on goodwill impairment testing process. There have been alternative positions of higher levels of non-compliance among clients of EY, KPMG and PWC. Apparently, the extent of compliant rates with HKFRS, including HKAS 36, is likely to be positively related to the probability of detecting and reporting material misstatements in the accounting system of a company. Variations in disclosure of goodwill impairment of audit firm clients are likely to be the result of audit quality variations in the multi-year data set. Based on the falling tendency of non-compliance levels with disclosure quality bearing on goodwill impairment, audit quality in the following years is judged to be higher than that in the previous years. Evidence obtained in this research may contribute to the literature by supporting the proposition that quality of Big 4 auditors is seen to be higher than that of non-Big 4 audit firms and audit quality among Big 4 auditors is subject to variation. References Balvers, R.J., Macdonald, B. and Miller, R.E. (1988), “Underpricing of new issues and the choice of auditor as a signal of investment banker reputation”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 63 No. 4, pp. 605-622. Becker, C.L., Defond, M.L., Jiambalvo, J. and Subramanyam, K.R. (1998), “The effect of audit quality on earnings management”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 1-24. Caneghem, T.V. (2004), “The impact of audit quality on earnings rounding-up behaviour: some U.K. evidence”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 771-786. Carlin, T.M., Finch, N. and Laili, N.H. (2009), “Investigating audit quality among Big 4 malaysian firms”, Asian Review of Accounting, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 96-114. Copley, P.A., Doucet, M.S. and Gaver, K.M. (1994), “A simultaneous equations analysis of quality control review outcomes and engagement fees for audit of recipients of federal financial assistance”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 69 No. 1, pp. 244-256. Dang, L. (2004), “Assessing actual audit quality”, PhD thesis, Drexel University, PA. Deangelo, L.E. (1981), “Audit size and audit quality”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 183-199. Defond, M.L. and Jiambalvo, J. (1991), “Incidence and circumstances of accounting errors”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 66 No. 3, pp. 643-655. 245 Audit quality differences Eisenberg, T. and Macey, J.R. (2003), “Was Arthur Andersen different? An empirical examination of major accounting firms’ audits of large clients”, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Vol. 1, pp. 263-300. Firth, M. and Smith, A. (1992), “Selection of auditor firms by companies in the new issue market”, Applied Economics, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 247-255. Fuerman, R.D. (2004), “Audit quality examined one large CPA firm at a time: mid-1990s empirical evidence of a precursor of Arthur Andersen’s collapse”, Corporate Ownership and Control, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 137-148. Hoogendoorn, M. (2006), “International accounting regulation and IFRS implementation in Europe and beyond – experiences with first-time adoption in Europe”, Accounting in Europe, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 23-26. Kit, F.Y. (2005), Evidence of Audit Quality Differences among Big Five Auditors: An Empirical Study, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon Tong. Krishnan, J. and Schauer, P.C. (2000), “The differentiation of quality among auditors: evidence from the not-for-profit sector”, Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 9-25. Moize, P. (1997), “Auditor reputation: the international empirical evidence”, International Journal of Auditing, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 61-74. Palmrose, Z.-V. (1988), “An analysis of auditor litigation and audit service quality”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 63 No. 1, pp. 55-73. Simunic, D.A. (2003), Audit Quality and Audit Firm Size: Revisited, The University of Bristish Columbia, Vancouver. Corresponding author Manh Dung Tran can be contacted at: manhdung@ktpt.edu.vn For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com 246 JED 21,2

File đính kèm:

a_longitudinal_study_of_audit_quality_differences_among_inde.pdf

a_longitudinal_study_of_audit_quality_differences_among_inde.pdf