Self-efficacy, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention among polish students in the context of industry 4.0: Assessing the effect of education level

This study aims to examine the effects of educational level on self-efficacy, perceived

behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention among Polish students in the context

of industry 4.0. By collecting data from 553 Polish students at universities and colleges

in Poland, author would employ the quantitative approach such as certain descriptive

statistics, explorative factor analysis, correlation coefficient analysis, ANOVA test and

multiple linear regressions to analyze the relationship between educational level, selfefficacy, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention. In addition, Chisquare and Cramer’s V tests are implemented to indicate the difference of educational

level in entrepreneurial intention. The research results show that there is a positive

relationship between educational level and entrepreneurial intention, while self-efficacy

and perceived behavioral control also have positive effects on entrepreneurial intention.

Moreover, Chi-Square and Cramer’s V test report that there is a strong evidence of

educational level in entrepreneurial intention but no differences in self-efficacy and

entrepreneurial intention.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Self-efficacy, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention among polish students in the context of industry 4.0: Assessing the effect of education level

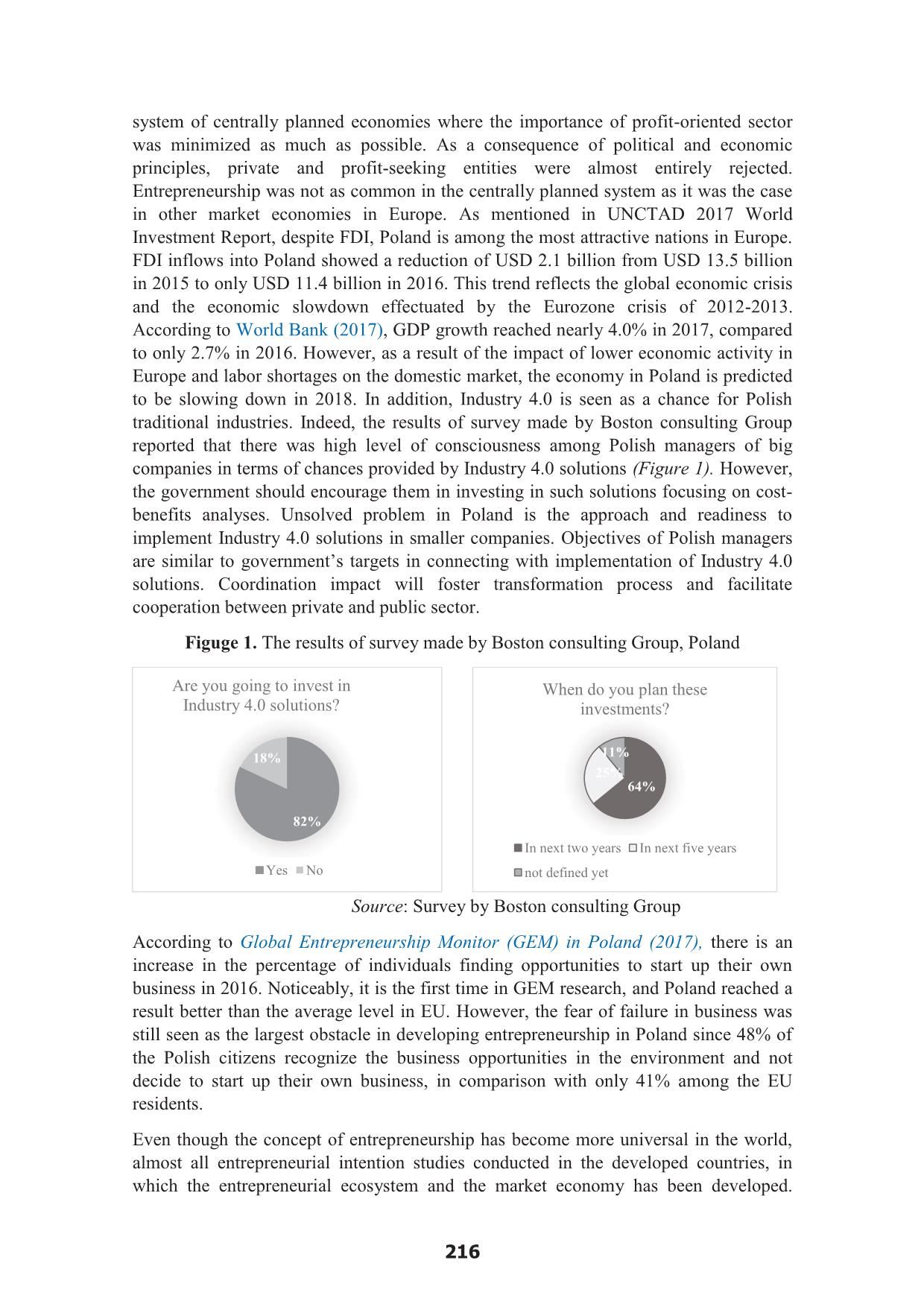

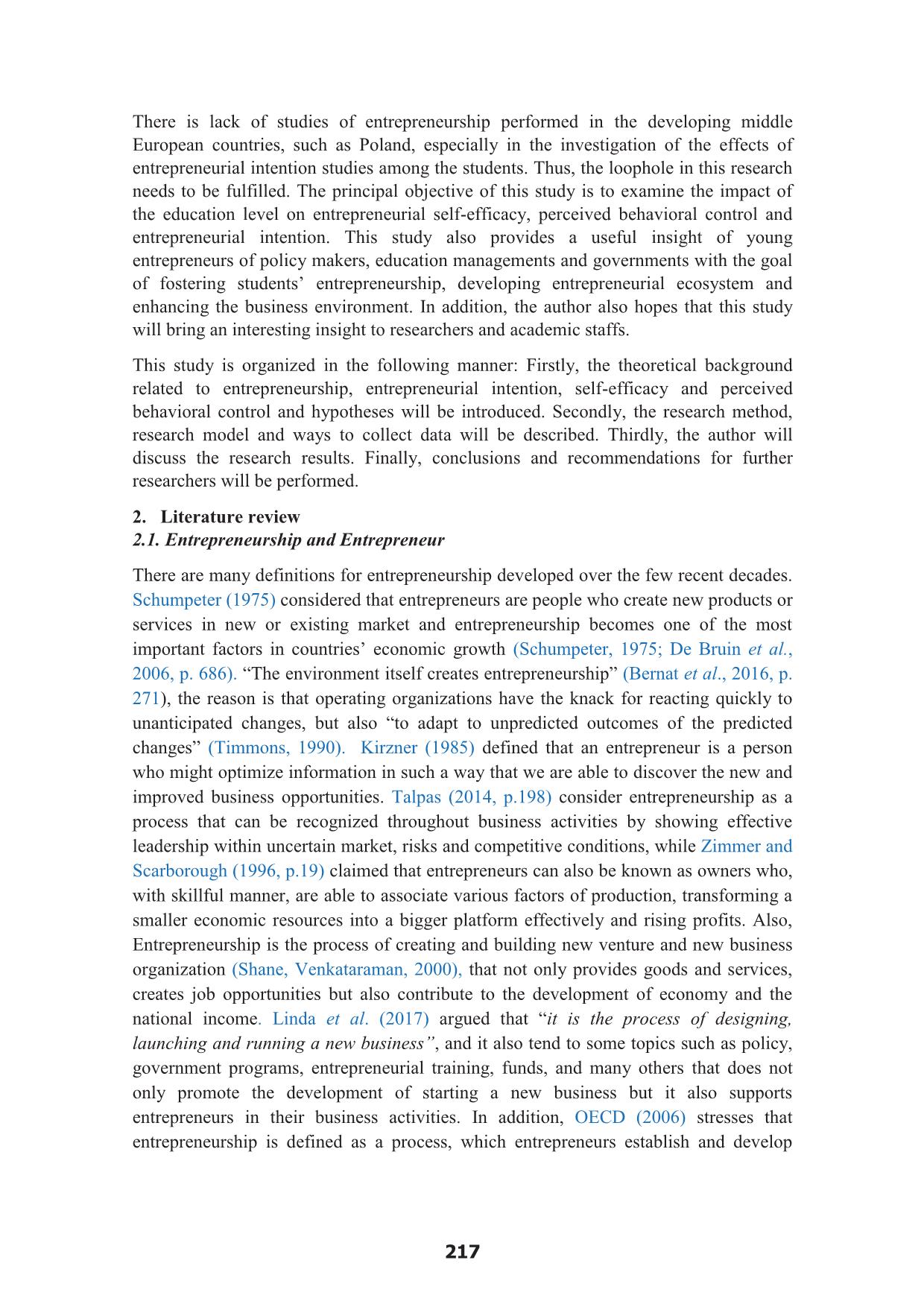

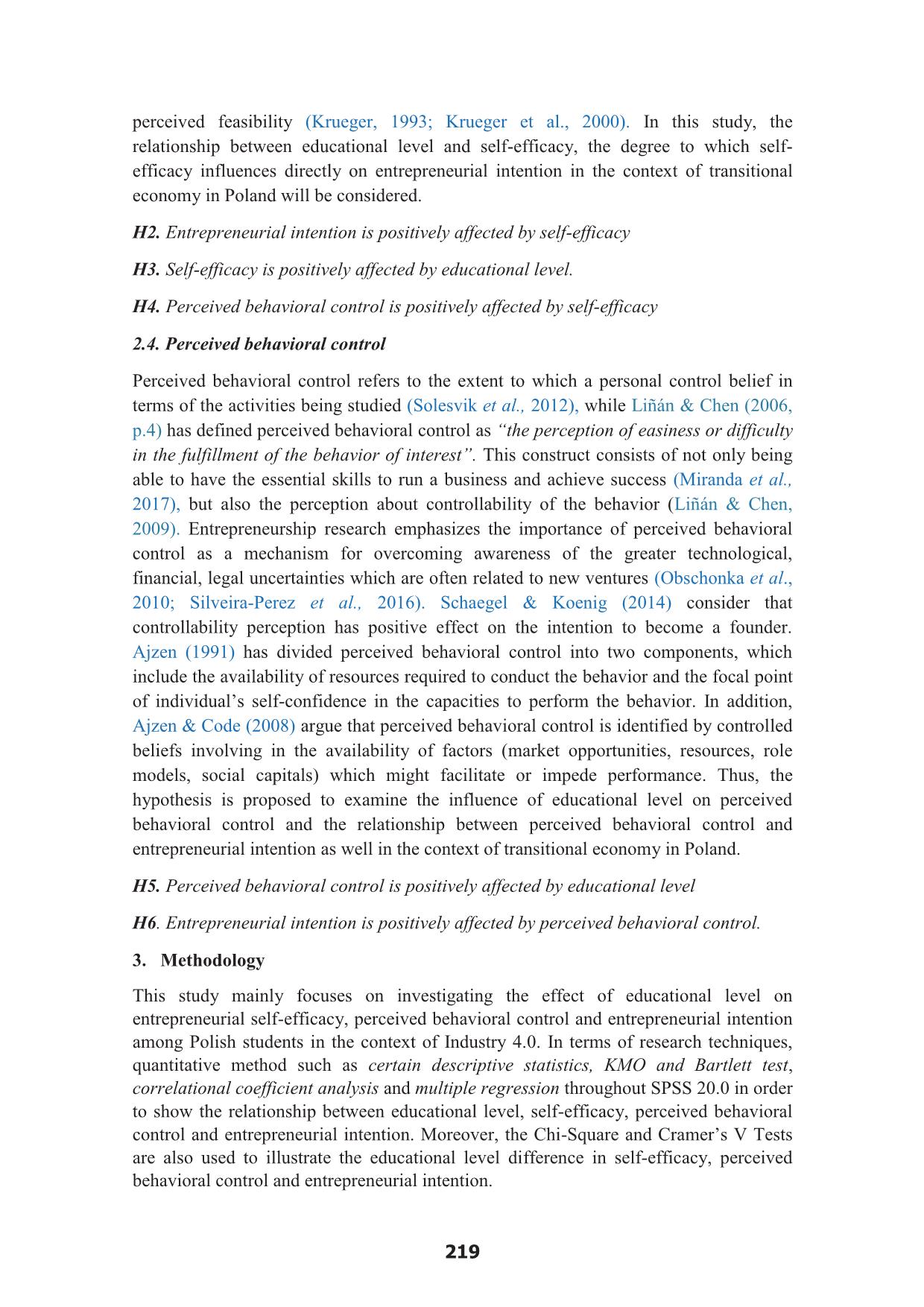

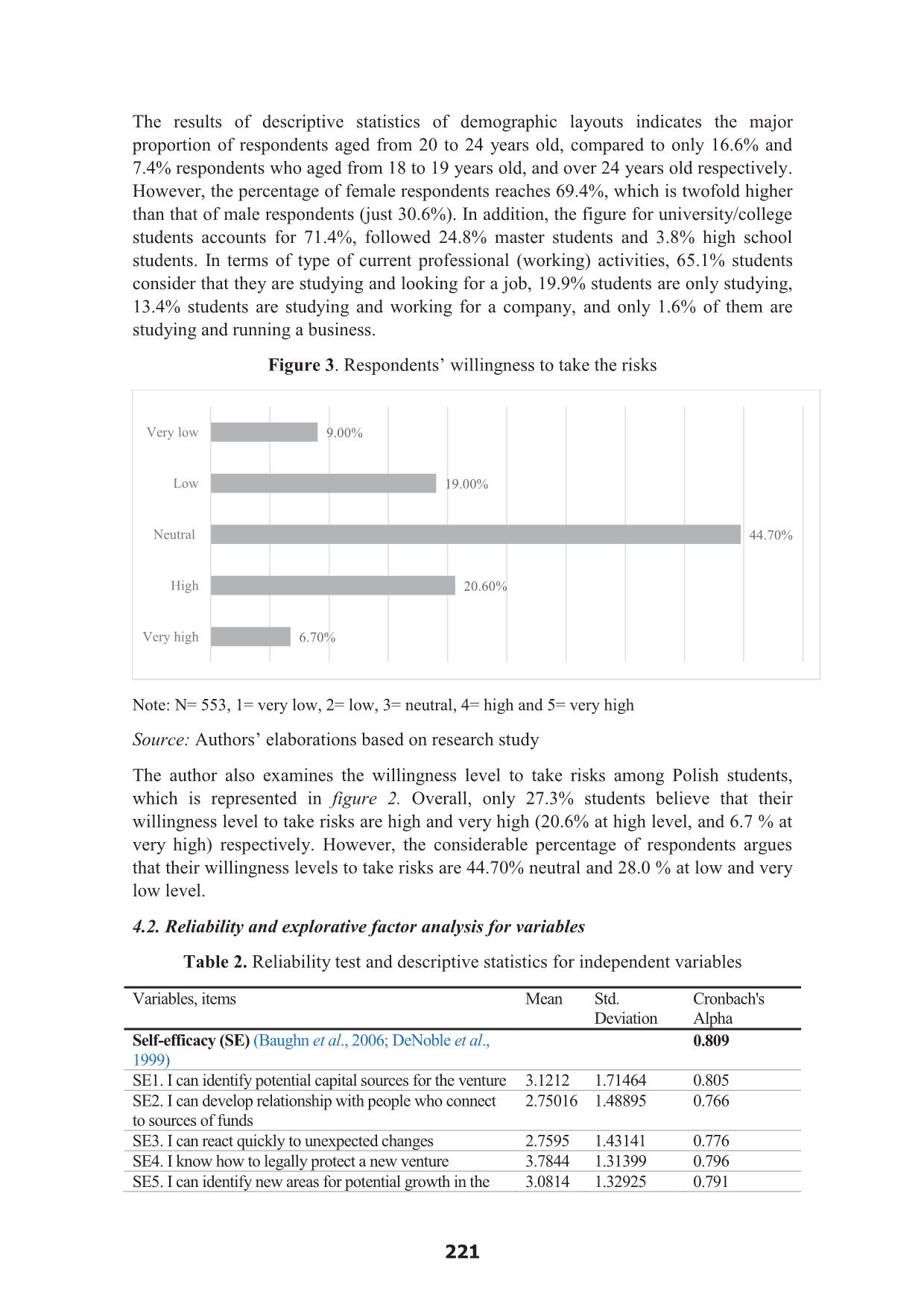

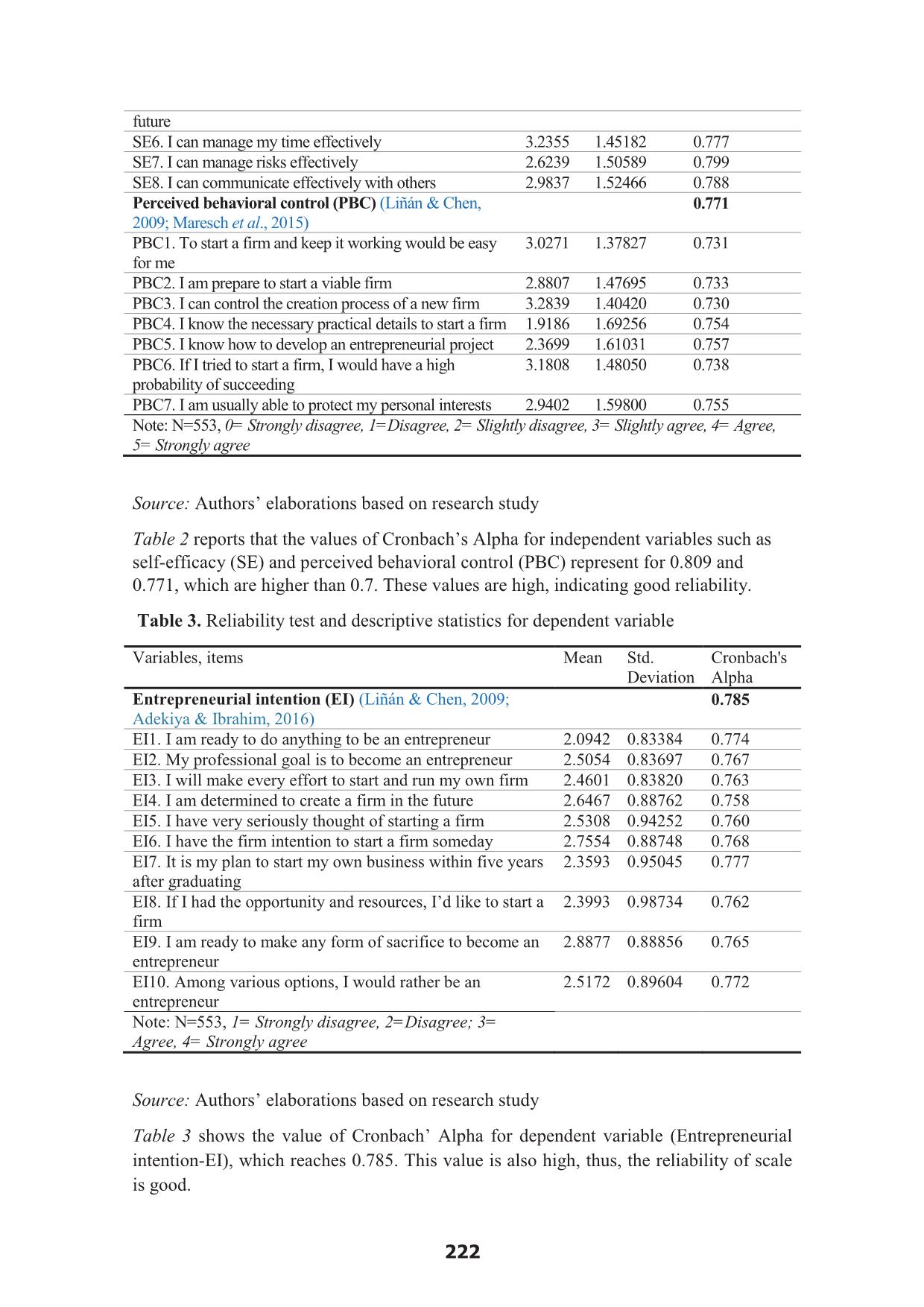

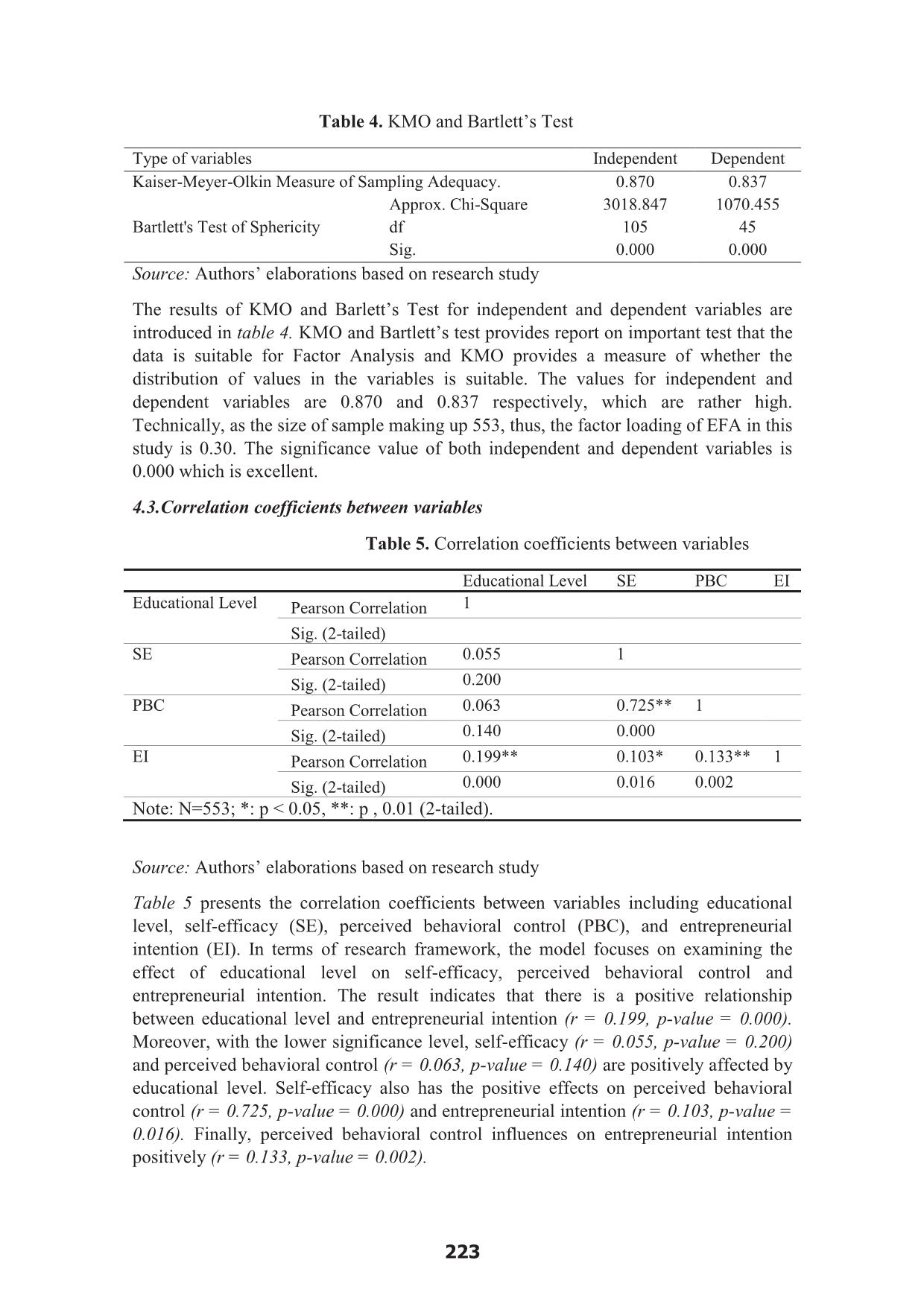

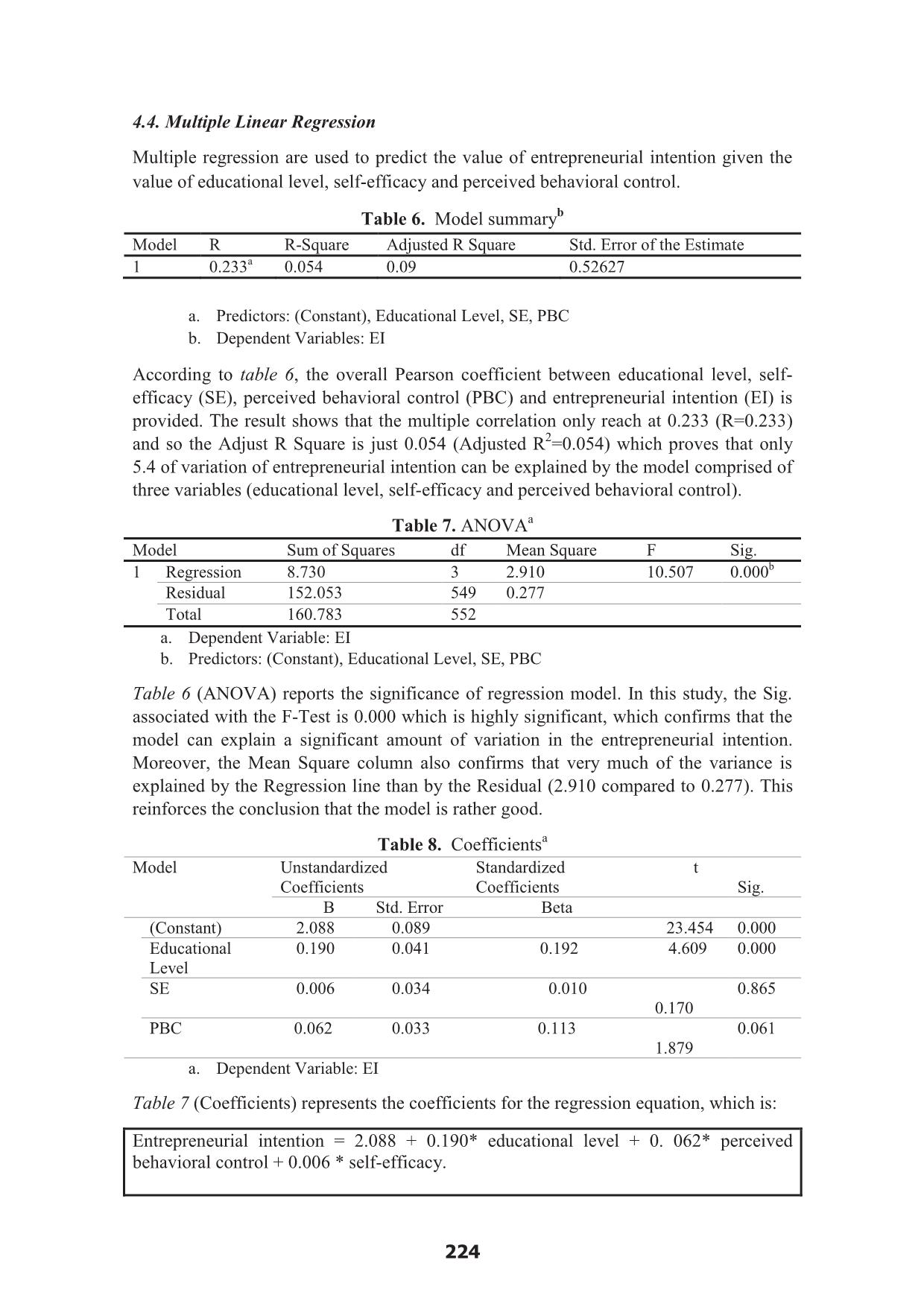

rol (PBC) and entrepreneurial intention (EI) is provided. The result shows that the multiple correlation only reach at 0.233 (R=0.233) and so the Adjust R Square is just 0.054 (Adjusted R2=0.054) which proves that only 5.4 of variation of entrepreneurial intention can be explained by the model comprised of three variables (educational level, self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control). Table 7. ANOVAa Model Sum of Squares df Mean Square F Sig. 1 Regression 8.730 3 2.910 10.507 0.000b Residual 152.053 549 0.277 Total 160.783 552 a. Dependent Variable: EI b. Predictors: (Constant), Educational Level, SE, PBC Table 6 (ANOVA) reports the significance of regression model. In this study, the Sig. associated with the F-Test is 0.000 which is highly significant, which confirms that the model can explain a significant amount of variation in the entrepreneurial intention. Moreover, the Mean Square column also confirms that very much of the variance is explained by the Regression line than by the Residual (2.910 compared to 0.277). This reinforces the conclusion that the model is rather good. Table 8. Coefficientsa Model Unstandardized Coefficients Standardized Coefficients t Sig. B Std. Error Beta (Constant) 2.088 0.089 23.454 0.000 Educational Level 0.190 0.041 0.192 4.609 0.000 SE 0.006 0.034 0.010 0.170 0.865 PBC 0.062 0.033 0.113 1.879 0.061 a. Dependent Variable: EI Table 7 (Coefficients) represents the coefficients for the regression equation, which is: Entrepreneurial intention = 2.088 + 0.190* educational level + 0. 062* perceived behavioral control + 0.006 * self-efficacy. 224 Particularly, the Standardized Coefficients Beta reports the contribution each variable makes to the model. In this study, educational level is the most important: a variation of 1 % in educational level would lead to a change of 19.0% in entrepreneurial intention (ߚଵ=0.190, p=0.000). Similarly, perceived behavioral control has the second strongest effect on entrepreneurial intention (ߚଶ=0.062, p=0.061> 0.005), followed by self- efficacy (ߚଷ=0.006, p=0.865> 0.005). 4.5. Chi-Square and Cramer’s V Tests Chi-Square and Cramer’s V Tests are employed to report the difference of educational level in self-efficacy, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention Chi-Square and Cramer’s V Tests for educational level difference in entrepreneurial self-efficacy Table 9. Chi-Square and Cramer’s V results for educational level difference in entrepreneurial self-efficacy Chi-Square Tests Symmetric Measures Value df Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) Value Approx. Sig. Pearson Chi-Square 98.912a 123 0.946 Phi 0.423 0.946 Likelihood Ratio 98.429 123 0.950 Cramer’s V 0.244 0.946 Linear-by-Linear Association 1.644 1 0.200 Note: N=553, a. 131 cells (78.0%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 0.02 Source: Authors’ elaborations based on research study The Chi-Square Tests in table 9 shows that the probability of differences this larger or larger occurring by chance is 0.946, which is higher than the normal 0.05 criterion level used (95% significance). Thus, there are no evidences of educational level difference in self-efficacy. Moreover, Cramer’s V change between 0 and 1, with 0 referring to no association and 1 showing the perfect association, the result in table 9 indicates that the value is 0.423, it means that the association between the educational level and entrepreneurial self-efficacy makes up the moderate level. Table 10. Chi-Square and Cramer’s V results for educational level difference in perceived behavioral control Chi-Square Tests Symmetric Measures Value df Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) Value Approx. Sig. Pearson Chi-Square 77.831a 105 0.978 Phi 0.375 0.978 Likelihood Ratio 89.636 105 0.858 Cramer’s V 0.217 0.978 Linear-by-Linear Association 2.176 1 0.140 Note: N=553, a. 109 cells (75.70%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 0.02 Source: Authors’ elaborations based on research study Analogously, table 10 presents that there is no difference between educational levels in perceived behavioral control and the association is moderate (Sig. = 0.978 > 0.05, φ =0.375). 225 Table 11. Chi-Square and Cramer’s V results for educational level difference in entrepreneurial intention Chi-Square Tests Symmetric Measures Value df Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) Value Approx. Sig. Pearson Chi-Square 112.473a 84 0.021 Phi 0.451 0.021 Likelihood Ratio 96.514 84 0.165 Cramer’s V 0.260 0.021 Linear-by-Linear Association 21.941 1 0.000 Note: N=553, a. 85 cells (73.3%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 0.02 Source: Authors’ elaborations based on research study Finally, the strong evidences in educational differences in entrepreneurial intention and the association is rather high (Sig. = 0.021 <0.05, φ =0.451). 5. Conclusion The objective of this study is to investigate the impacts of educational level, self- efficacy, and perceived behavioral control on entrepreneurial intention among Polish students in the context of Industry 4.0. The research results show that the educational level, self-efficacy, perceived behavioral control have positive effects on entrepreneurial intention at the high level (p-value <0.05). Thus, the hypotheses including H1, H2, H4, H6 are accepted. In addition, educational level is seen as the most influential factor in entrepreneurial intention, followed by perceived behavioral control, and self-efficacy. In addition, there are the strong evidence of educational level differences in entrepreneurial intention, but no education differences in self-efficacy and perceived behavior control. However, there are some restrictions. Firstly, the author only focuses on figuring out the direct effects of educational level, self-efficacy and perceived behavior control on entrepreneurial intention, the further researches should extend the research model by supplementing mediating variables, or using different variables. Secondly, the quantitative method through the availability sample can be seen as a restriction of this study, the further research should use the different approach to collect data in order to increase the significance level. References Adekiya, A. A. & Ibrahim, F. (2016). Entrepreneurship intention among students. The antecedent role of culture and entrepreneurship training and development. The International Journal of Management Education, 14, 116-132. Baughn, C.C, Cao, J.S.R, Le, L.T.M, Lim, V. A., & Neupert, K. E. (2006). Normative, Social and Cognitive predictors of entrepreneurial interest in China, Vietnam and The Philippines. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 57-77. Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. Ajzen, I. (1987). Attitudes, traits, and actions: dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology, In: Berkowitz, L. (Ed.). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 20. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA, 1–63. 226 Ajzen, I., Cote, N.G. (2008). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior. In: Crano, W.D., Prislin, R., editors. Attitudes and Attitude Change. New York: Psychology Press. 289- 311. Bandura, A (1986). The Social Foundations of Thought and Action, Englewood Cliffs. NJ: Prentice-Hall. Bandura, A. (1987). Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Bernat T., Maciejewska-Skrendo A. & Sawczuk M. (2016). Entrepreneurship-Risk- Genes, experimental study. Part 1- entrepreneurship and risk relation, Journal of International Studies, 9 (3), 207-278. Bird, B. and Jellinek, M. (1988). The Operation of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Winter, 21-29. Boston Consulting Group (2017), The results of survey, https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/07_2017.01.31- 02.01_jan_stanilko_industry_4.0.pdf (09.08.2018) Chen, G., Gully, M.S. and Eden, D. (2004). General self-efficacy and self-esteem: toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self-evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 75-95. Cole, A.H. (1965). An approach to the study of entrepreneurship, in Aitken, H.G. (ed.), Explorations in enterprise. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 30- 44. Crant, J.M. (1996). The proactive personality scale as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management. 34 (3), 42-49. De Bruin, A., Brush, C. G. & Welter, F. (2006). Advancing a framework for coherent research on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 16 (1), 7-25. De Noble, A.F., Jung D. & Ehrlich, S.B (1999). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. MA: Babson College, 73-87. Do, B. & Dadvari, A. (2017). The influence of the dark triad on the relationship between entrepreneurial attitude orientation and entrepreneurial intention: A study among students in Taiwan University. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22, 185-191. Douglas, E.J. and Shepherd, D.A. (1997), Why entrepreneurs create businesses: a utility maximizing response, Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. 17, 185-186. Esfandiar, K., Sharifi-Tehrani, M., Pratt, S. & Altinay, L. (2017). Understanding entrepreneurial intention: A developed integrated structural model approach, Journal of Business Research. (11.04.2018). 227 Fishbein, M.& Ajzen, I. (1975) Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Addison-Wesley, New York. Gartner, W.B, Bird, B.J. & Starr, J. (1992). Acting as if: Differentiating Entrepreneurial from organizational Behavior, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(3), 13-32. Guerrero, M., Rialp, J., & Urbano, D. (2008). The impact of desirability and feasibility on entrepreneurial intentions: A structural equation model. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(1), 35–50. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report- Poland (2017). Polska Agencja Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości, GEM. Warszawa. Kirzner, I. (1985). Discovery and the capitalist process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Iakovleva, T., Kolvereid, L., Gorgievski, M. & Sorhaug, O. (2014). Comparison of perceived barriers to entrepreneurship in Eastern and Western European countries. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management,18, 115–133. Kelley, D. J., Bosma, N., and Amorós, J. E. (2011). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2010 Global Report. Babson Park, MA: Babson College und Santiago, Chile: Universidad del Desarrollo. Kolvereid, L. (1996). Organizational employment versus self-employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 20 (3), 23-31. Krueger, N.F. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 18 (1), 5–21. Krueger, N. F., & Brazeal, D. V. (1994), Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs, Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, Vol. 18, No.1, pp. 91-105. Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing. 15 (5/6), 411–432. Krueger, N. (2008). Entrepreneurial Resilience: Real and Perceived Barriers to Implementing Entrepreneurial Intentions. Working Paper, SSRN, (11.04.2018). Lee, L., Wong, P. K., Foo, M. D. & Leung, A. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of organization and individual factors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26. 124-136. Liñán, F. & Chen. Y. (2009). Development and Cross-Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 539-617. 228 Liñán, Fr. and Chen, Y. (2006). Testing the Entrepreneurial Intention Model on a Two- Country Sample. Departament d'Economia de l'Empresa. Linda, L.L., Ana, V.P., & Cheng-Nam, C. (2017). Factors related to the intention of starting a new business in EL Salvador. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22, 212-222. Maresch, D., Harms. R, Kailer, N. & Wimmer-Wurm, B. (20015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 104, 172-179. Miranda, F.J., Chamorro-Mera, A. & Rubio, S. (2017). Academic entrepreneurship in Spanish universities: An analysis of determinants of entrepreneurial intention. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 23, 113-122. Moriano, J.A., Gorgievski, M.J., Laguna, M., Stephan, U. and Zarafshani, K. (2012). A cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Career Development. 39 (2), 162-185. Obschonka, M., Silbereisen, R. K., & Schmitt-Rodermund, E. (2010). Entrepreneurial intention as developmental outcome. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(1), 63–72. OECD. (2006). Entrepreneurship and local economic development. USA: OECD LEED Publishers. Schumpeter, J.A. (1975). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. 3rd edition, New York, Harper and Row. Schlaegel, C., & Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A metaanalytic test and integration of competing models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332. Shane, S. & Venkataraman. S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217-226. Silveira-Pérez, Y., Cabeza-Pullés, D., & Fernández-Pérez, V. (2016). Emprendimiento: perspectiva cubana en la creación de empresas familiares. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 22(2), 70–77. Solesvik, M., Westhead, P., Kolvereid, L. and Matlay, H. (2012). Student intentions to become self-employed: The Ukrainian context. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19 (3), 441–460. DOI: Talpas, P. (2014). Integration of Romani women on the labor market. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 10 (1), 198-203. Timmons J.A. (1990). New Venture Creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st Century, Irwin/McGraw-Hill, Boston. Weber, M (1978). Economy and Society. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. 229 WORLD BANK (2017). Poland’s GDP Growth to Reach 4% in 2017, Before Slowing Down in 2018, Says World Bank. release/2017/10/19/poland-gdp-growth-to-reach-4-2017-before-slowing-down-2018- says-world-bank (20.02.2018) Zimmerer, T. & Scarborough, N. M. (1996). Entrepreneurship and new venture formation. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. 230

File đính kèm:

self_efficacy_perceived_behavioral_control_and_entrepreneuri.pdf

self_efficacy_perceived_behavioral_control_and_entrepreneuri.pdf