Methods of spatial point pattern analysis applied in forest ecology

Spatial patterns of forest trees result from complex dynamic processes such as

establishment, dispersal, mortality, land use and climate (Franklin et al. 2010), especially in

tropical forests which are among the world‘s most species-rich terrestrial ecosystems. Spatial

correlation of trees may provide evidences of ecological interactions which are assumed to be

drivers of spatial pattern in plant communities. Spatial pattern analysis in ecology has received

increasing attention of ecologists and mathematicians over the last decades. Furthermore, it is

stimulated by the development of spatial point pattern methods and relevant computer

applications.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Bạn đang xem tài liệu "Methods of spatial point pattern analysis applied in forest ecology", để tải tài liệu gốc về máy hãy click vào nút Download ở trên

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Methods of spatial point pattern analysis applied in forest ecology

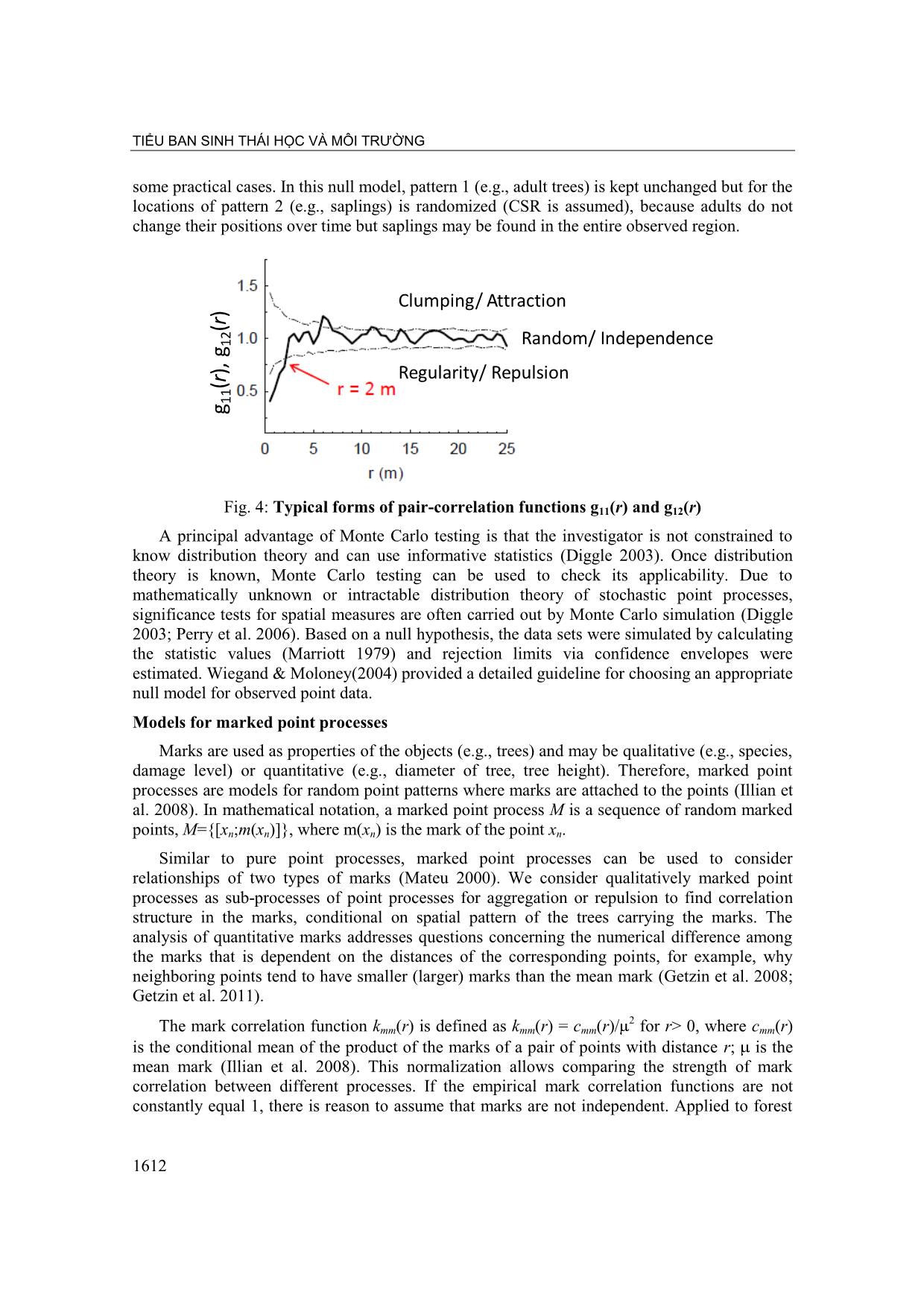

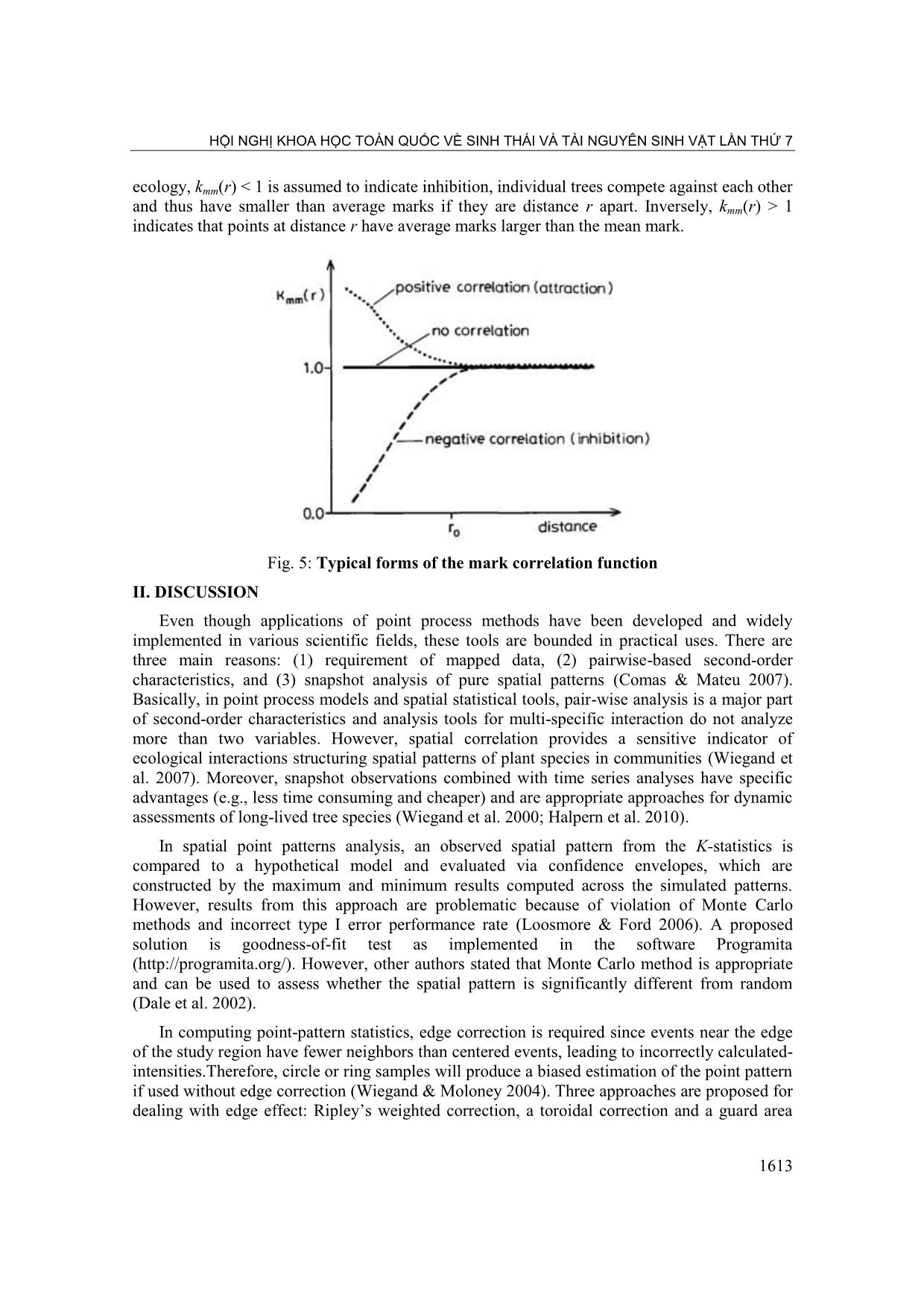

relation structure in the marks, conditional on spatial pattern of the trees carrying the marks. The analysis of quantitative marks addresses questions concerning the numerical difference among the marks that is dependent on the distances of the corresponding points, for example, why neighboring points tend to have smaller (larger) marks than the mean mark (Getzin et al. 2008; Getzin et al. 2011). 2 The mark correlation function kmm(r) is defined as kmm(r) = cmm(r)/ for r> 0, where cmm(r) is the conditional mean of the product of the marks of a pair of points with distance r; is the mean mark (Illian et al. 2008). This normalization allows comparing the strength of mark correlation between different processes. If the empirical mark correlation functions are not constantly equal 1, there is reason to assume that marks are not independent. Applied to forest 1612 . HỘI NGHỊ KHOA HỌC TOÀN QUỐC VỀ SINH THÁI VÀ TÀI NGUYÊN SINH VẬT LẦN THỨ 7 ecology, kmm(r) < 1 is assumed to indicate inhibition, individual trees compete against each other and thus have smaller than average marks if they are distance r apart. Inversely, kmm(r) > 1 indicates that points at distance r have average marks larger than the mean mark. Fig. 5: Typical forms of the mark correlation function II. DISCUSSION Even though applications of point process methods have been developed and widely implemented in various scientific fields, these tools are bounded in practical uses. There are three main reasons: (1) requirement of mapped data, (2) pairwise-based second-order characteristics, and (3) snapshot analysis of pure spatial patterns (Comas & Mateu 2007). Basically, in point process models and spatial statistical tools, pair-wise analysis is a major part of second-order characteristics and analysis tools for multi-specific interaction do not analyze more than two variables. However, spatial correlation provides a sensitive indicator of ecological interactions structuring spatial patterns of plant species in communities (Wiegand et al. 2007). Moreover, snapshot observations combined with time series analyses have specific advantages (e.g., less time consuming and cheaper) and are appropriate approaches for dynamic assessments of long-lived tree species (Wiegand et al. 2000; Halpern et al. 2010). In spatial point patterns analysis, an observed spatial pattern from the K-statistics is compared to a hypothetical model and evaluated via confidence envelopes, which are constructed by the maximum and minimum results computed across the simulated patterns. However, results from this approach are problematic because of violation of Monte Carlo methods and incorrect type I error performance rate (Loosmore & Ford 2006). A proposed solution is goodness-of-fit test as implemented in the software Programita ( However, other authors stated that Monte Carlo method is appropriate and can be used to assess whether the spatial pattern is significantly different from random (Dale et al. 2002). In computing point-pattern statistics, edge correction is required since events near the edge of the study region have fewer neighbors than centered events, leading to incorrectly calculated- intensities.Therefore, circle or ring samples will produce a biased estimation of the point pattern if used without edge correction (Wiegand & Moloney 2004). Three approaches are proposed for dealing with edge effect: Ripley‘s weighted correction, a toroidal correction and a guard area 1613 . TIỂU BAN SINH THÁI HỌC VÀ MÔI TRƯỜNG correction (Haase 1995; Yamada & Rogerson 2003). The major finding of Yamada & Rogerson(2003) is that the K-function method adjusted by either the Ripley or toroidal edge is more powerful than the guard area method. Among two alternatives to estimate the bivariate K- function (numeric and analytical methods), numeric approaches are integrated and use an underlying grid of cells. Therefore, analyses using Programita software do not require edge correction (Wiegand & Moloney 2004). Generally, plant community dynamics are driven by spatially dependent birth, death and growth processes and closely embedded in a heterogeneous landscape (Law et al. 2009). From multispecies spatial patterns analyzed, ecologists may use spatio-temporal information to tackle basic questions. Moreover, plants are obviously not points, marks characterized for individual plants (e.g., species, biomass, height, so on) and environmental data need to be considered as they are highly relevant (Illian & Burslem 2007). Therefore, theoretical and empirical issues are closely connected with their estimations and infer to the real dynamic processes generating patterns of plant communities. Spatial point pattern analysis is stimulated by large and technical literature in mathematics and plant ecology, moreover by strongly developed applications in computer science (Law et al. 2009). III. CONCLUSION Analysis of spatial point pattern has a long history in plant ecology and there are a number of tests available to characterise and explore such data. However, these tests do not all perform equally and all have their weaknesses and strengths. As a result, it is suggested that a suite of statistics is used to characterise spatial point patterns, otherwise there is a risk that the description of the pattern will be partially determined by the test chosen. We have to note that point-pattern analysis is a descriptive analysis. Even if a particular null model describes our pattern well, it is not appropriate to conclude that the mechanism behind the null model is the mechanism responsible for our pattern. Other mechanisms may lead to exactly the same pattern. However, point-pattern analysis helps to characterize our pattern and to put forward hypotheses on the underlying mechanisms that should be tested in subsequent steps in the field. REFERENCE 1. Bruno, J. F., Stachowicz, J. J. & Bertness, M. D., 2003. Inclusion of facilitation into ecological theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 18(3): 119-125. 2. Callaway, R. M. & Walker, L. R., 1997. Competition and facilitation: A synthetic approach to interactions in plant communities. Ecology 78(7): 1958-1965. 3. Chave, J., 2004. Neutral theory and community ecology. Ecology Letters 7(3): 241-253. 4. Comas, C. & Mateu, J., 2007. Modelling forest dynamics: A perspective from point process methods. Biometrical Journal 49(2): 176-196. 5. Condit, R., Ashton, P. S., Baker, P., Bunyavejchewin, S., Gunatilleke, S., Gunatilleke, N., Hubbell, S. P., Foster, R. B., Itoh, A., LaFrankie, J. V., Lee, H. S., Losos, E., Manokaran, N., Sukumar, R. & Yamakura, T., 2000. Spatial patterns in the distribution of tropical tree species. Science 288(5470): 1414-1418. 6. Condit, R., Hubbell, S. P. & Foster, R. B.,1994. Density-dependence in 2 understorey tree species in a Neotropical forest. Ecology 75(3): 671-680. 1614 . HỘI NGHỊ KHOA HỌC TOÀN QUỐC VỀ SINH THÁI VÀ TÀI NGUYÊN SINH VẬT LẦN THỨ 7 7. Connell, J. H., 1971. On the role of natural enemies in preventing competitive exclusion in some marine animals and in rain forest trees. Dynamics of Populations Pudoc, Wageningen, P. J. den Boer & G. Gradwell: 298-312. 8. Connell, J. H., 1978: Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs-High diversity of trees and corals is maintained only in a non-equilibrium state. Science 199(4335): 1302- 1310. 9. Dale, M. R. T., Dixon, P., Fortin, M. J., Legendre, P., Myers, D. E. & Rosenberg, M. S., 2002. Conceptual and mathematical relationships among methods for spatial analysis. Ecography 25(5): 558-577. 10. Dickie, I. A., Schnitzer, S. A., Reich, P. B. & Hobbie, S. E., 2007. Is oak establishment in old-fields and savanna openings context dependent? Journal of Ecology 95(2): 309-320. 11. Diggle, P. J. ,2003. Statistical analysis of spatial point patterns. London, Arnold (Hodder Headline Group). 12. Franklin, J., Anselin, L. & Rey, S. J., 2010. Spatial Point Pattern Analysis of Plants Perspectives on Spatial Data Analysis, Springer Berlin Heidelberg: 113-123. 13. Getzin, S., Wiegand, K., Schumacher, J. & Gougeon, F. A., 2008. Scale-dependent competition at the stand level assessed from crown areas. Forest Ecology And Management 255(7): 2478-2485. 14. Getzin, S., Worbes, M., Wiegand, T. & Wiegand, K., 2011. Size dominance regulates tree spacing more than competition within height classes in tropical Cameroon. Journal of Tropical Ecology 27: 93-102. 15. Goreaud, F. & Pelissier, R. 2003: Avoiding misinterpretation of biotic interactions with the intertype K-12-function: population independence vs. random labelling hypotheses. Journal of Vegetation Science 14(5): 681-692. 16. Haase, P., 1995. Spatial pattern-analysis in ecology based on Ripley's K-function: Introduction and methods of edge correction. Journal of Vegetation Science 6(4): 575-582. 17. Halpern, C. B., Antos, J. A., Rice, J. M., Haugo, R. D. & Lang, N. L., 2010. Tree invasion of a montane meadow complex: temporal trends, spatial patterns, and biotic interactions. Journal of Vegetation Science 21(4): 717-732. 18. Harms, K. E., Condit, R., Hubbell, S. P. & Foster, R. B., 2001. Habitat associations of trees and shrubs in a 50-ha neotropical forest plot. Journal Of Ecology 89(6): 947-959. 19. Hubbell, S. P., 2001. The unified neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography. Princeton, Princeton University Press. 20. Illian, J. & Burslem, D., 2007. Contributions of spatial point process modelling to biodiversity theory. Journal de la société française de statistique 148(1): 9-29. 21. Illian, J., Stoyan, D., Stoyan, H. & Penttinen, A., 2008. Statistical Analysis and Modelling of Spatial Point Patterns. Sussex, Wiley. 22. Janzen, D. H., 1970. Herbivores and the number of tree species in tropical forests. American Naturalist 104(940): 501. 1615 . TIỂU BAN SINH THÁI HỌC VÀ MÔI TRƯỜNG 23. Lan, G., Getzin, S., Wiegand, T., Hu, Y., Xie, G., Zhu, H. & Cao, M., 2012. Spatial Distribution and Interspecific Associations of Tree Species in a Tropical Seasonal Rain Forest of China. Plos One 7(9). 24. Lan, G., Zhu, H., Cao, M., Hu, Y., Wang, H., Deng, X., Zhou, S., Cui, J., Huang, J., He, Y., Liu, L., Xu, H. & Song, J., 2009. Spatial dispersion patterns of trees in a tropical rainforest in Xishuangbanna, southwest China. Ecological Research 24(5): 1117-1124. 25. Law, R., Illian, J., Burslem, D. F. R. P., Gratzer, G., Gunatilleke, C. V. S. & Gunatilleke, I. A. U. N., 2009. Ecological information from spatial patterns of plants: insights from point process theory. Journal Of Ecology 97(4): 616-628. 26. Loosmore, N. B. & Ford, E. D., 2006. Statistical inference using the G or K point pattern spatial statistics. Ecology 87(8): 1925-1931. 27. Marriott, F. H. C., 1979. Barnard's Monte Carlo Tests: How Many Simulations? Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics) 28(1): 75-77. 28. Mateu, J., 2000. Second-order characteristics of spatial marked processes with applications. Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications 1(1): 145-162. 29. Murrell, D. J., 2009. On the emergent spatial structure of size-structured populations: when does self-thinning lead to a reduction in clustering? Journal Of Ecology 97(2): 256- 266. 30. Nathan, R. & Muller-Landau, H. C., 2000. Spatial patterns of seed dispersal, their determinants and consequences for recruitment. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 15(7): 278- 285. 31. Perry, G. L. W., Miller, B. P. & Enright, N. J., 2006. A comparison of methods for the statistical analysis of spatial point patterns in plant ecology. Plant Ecology 187(1): 59-82. 32. Peters, H. A., 2003. Neighbour-regulated mortality: the influence of positive and negative density dependence on tree populations in species-rich tropical forests. Ecology Letters 6(8): 757-765. 33. Ripley, B. D., 1976. The Second-Order Analysis of Stationary Point Processes Journal of Applied Probability 13(2): 255-266 34. Sterner, R. W., Ribic, C. A. & Schatz, G. E., 1986. Testing for life historical changes in spatial patterns of four tropical tree species. Journal Of Ecology 74(3): 621-633. 35. Stoyan, D. & Penttinen, A., 2000. Recent applications of point process methods in forestry statistics. Statistical Science 15(1): 61-78. 36. Stoyan, D. & Stoyan, H., 1994. Fractals, random shapes, and point fields: Methods of geometrical statistics. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons. 37. Tilman, D., 1994. Competition and biodiversity in spatially structure habitats. Ecology 75(1): 2-16. 38. Wiegand, K., Jeltsch, F. & Ward, D., 2000. Do spatial effects play a role in the spatial distribution of desert-dwelling Acacia raddiana? Journal of Vegetation Science 11(4): 473- 484. 1616 . HỘI NGHỊ KHOA HỌC TOÀN QUỐC VỀ SINH THÁI VÀ TÀI NGUYÊN SINH VẬT LẦN THỨ 7 39. Wiegand, T., Gunatilleke, C. V. S., Gunatilleke, I. A. U. N. & Huth, A., 2007. How individual species structure diversity in tropical forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104(48): 19029-19033. 40. Wiegand, T., Gunatilleke, S. & Gunatilleke, N., 2007. Species associations in a heterogeneous Sri lankan dipterocarp forest. American Naturalist 170(4): E77-E95. 41. Wiegand, T. & Moloney, K. A., 2004. Rings, circles, and null-models for point pattern analysis in ecology. Oikos 104(2): 209-229. 42. Yamada, I. & Rogerson, P. A., 2003. An empirical comparison of edge effect correction methods applied to K-function analysis. Geographical Analysis 35(2): 97-109. CÁC PHƢƠNG PHÁP PHÂN TÍCH MÔ HÌNH ĐIỂM KHÔNG GIAN ỨNG DỤNG TRONG SINH THÁI RỪNG Nguyễn Hồng Hải Đại học Lâm nghiệp Việt Nam TÓM TẮT Rất nhiều các phương pháp phân tích về mô hình điểm đã được phát triển trong nhiều lĩnh vực khoa học. Thống kê bậc nhất mô tả sự biến động của mật độ các điểm trên phạm vi lớn của vùng nghiên cứu, trong khi tính chất của bậc hai là tổng hợp thống kê của khoảng cách giữa các điểm và cung cấp khả năng nhận dạng các loại mô hình ở các phạm vi khác nhau. Thống kê bậc hai dựa vào hàm Ripley‘s K được sử dụng rộng rãi trong sinh thái để mô tả mô hình không gian và để phát triển giả thuyết về quá trình đang diễn ra. Mục tiêu của bài báo này là thống kê lại các phương pháp phân tích mô hình điểm không gian có thể ứng dụng trong sinh thái rừng. Chúng tôi đã tổng hợp các vấn đề liên quan trong phần thảo luận và kết luận. Chúng tôi cũng giới thiệu phần mềm Programita để ứng dụng tất cả các phương pháp được trình bày trong bài báo. 1617

File đính kèm:

methods_of_spatial_point_pattern_analysis_applied_in_forest.pdf

methods_of_spatial_point_pattern_analysis_applied_in_forest.pdf