First language (L1) as a mediational tool in peer interaction in English speaking tasks by EFL college students in Vietnam

The sociocultural theory providesnew perspectives towards learning, shedding new lights on the

potential role of the first language (L1) in language learning conducive to linguistic development and

higher mental achievements.Drawing on the sociocultural theory, the authorinvestigates the use of L1 in

speaking tasks by EFL college students in Vietnam.The study provides insights into the use of L1 in the

EFL learning in English speaking tasks. Data collection was carried out by videotaping five pairs of students on completing two speaking tasks. The findings reveal the mediational functions of L1 in peer interaction with two prominent features of attention to vocabulary and meaning, and task elaboration. The L1

use in the two speaking tasks is reported in close relation tolearners’ proficiency and task types. The results also claim the use of L1 in promoting the target language learning, which provides the pedagogical

implications for using the mother tongue in teaching and learning English in the peer context

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: First language (L1) as a mediational tool in peer interaction in English speaking tasks by EFL college students in Vietnam

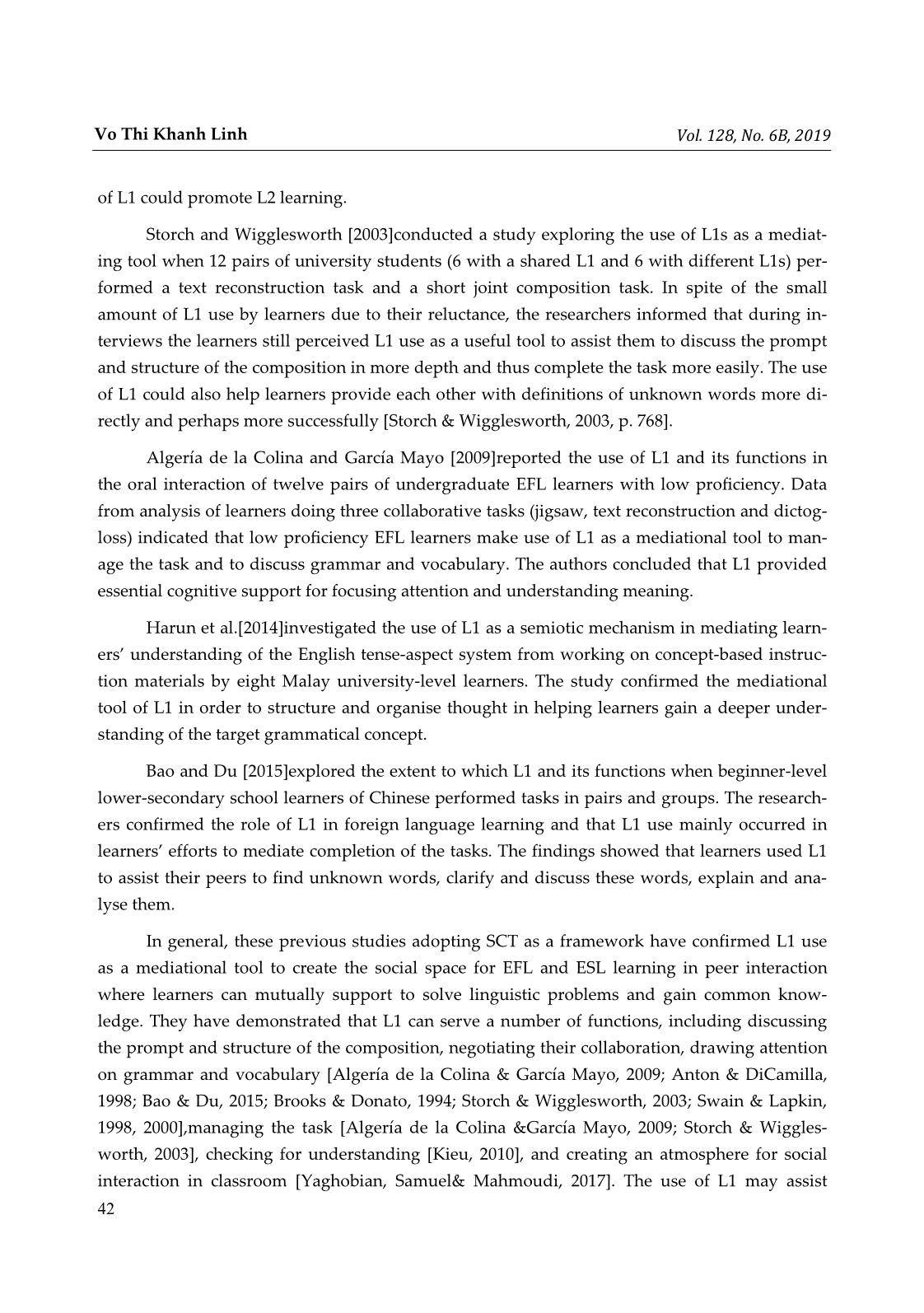

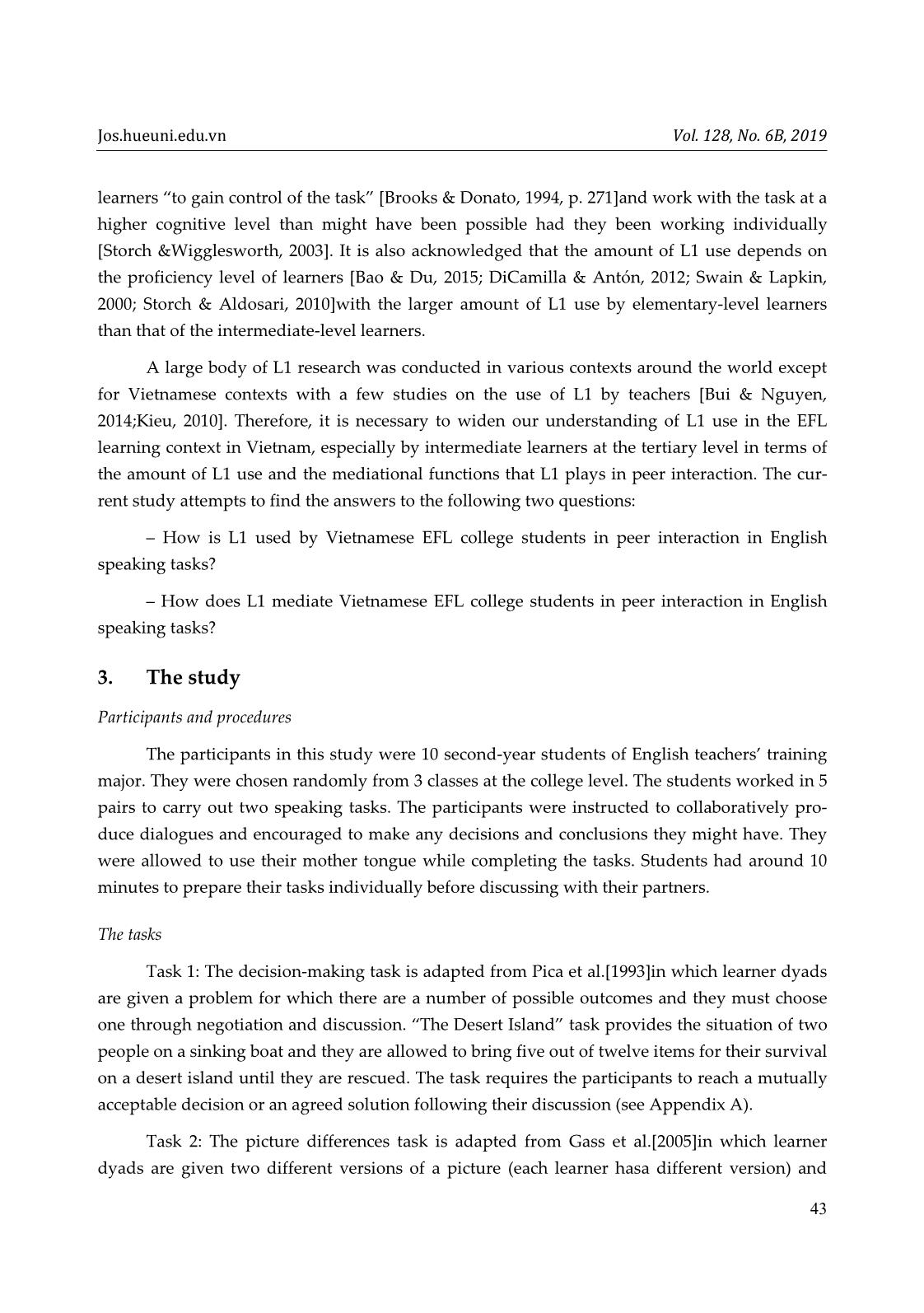

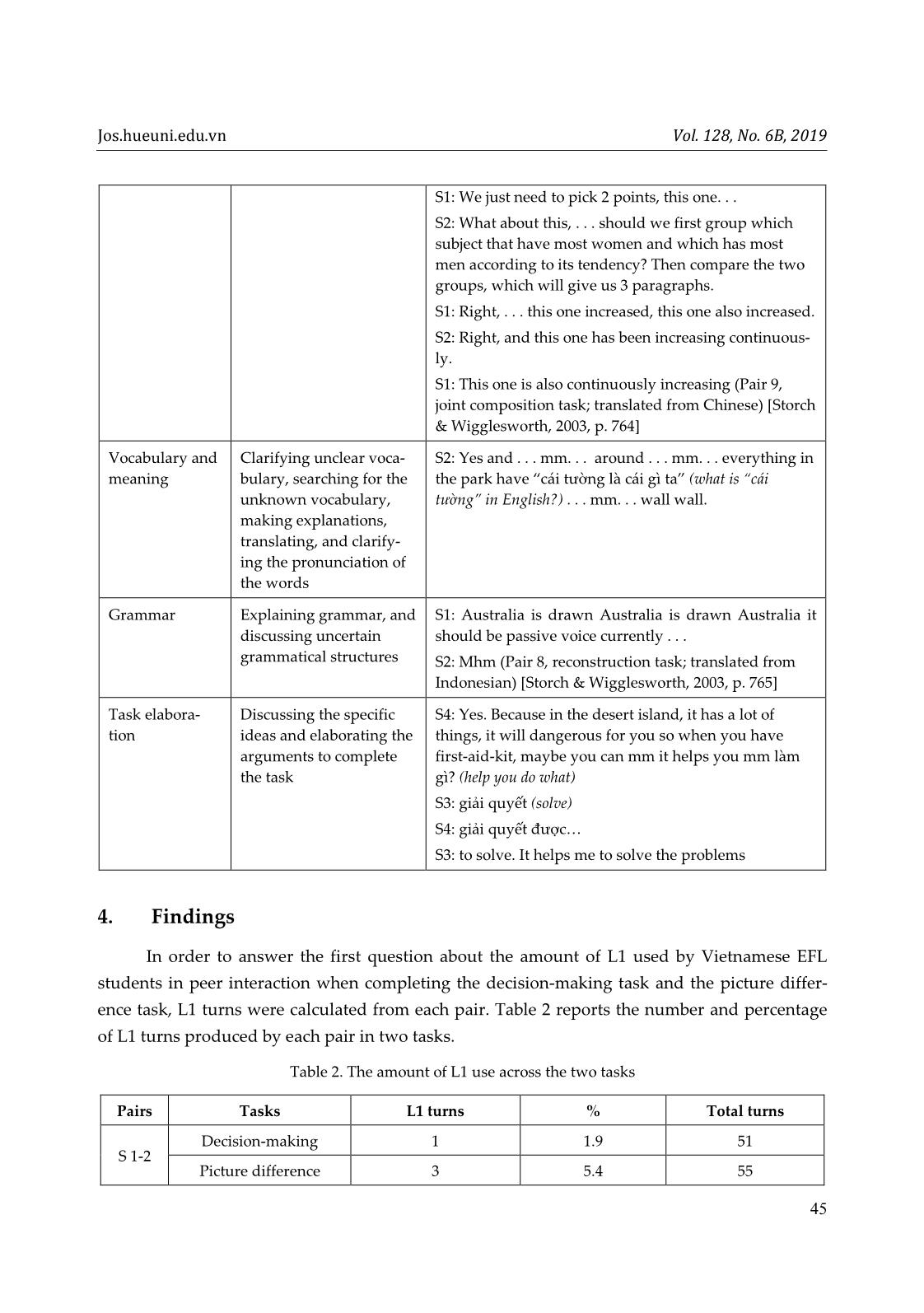

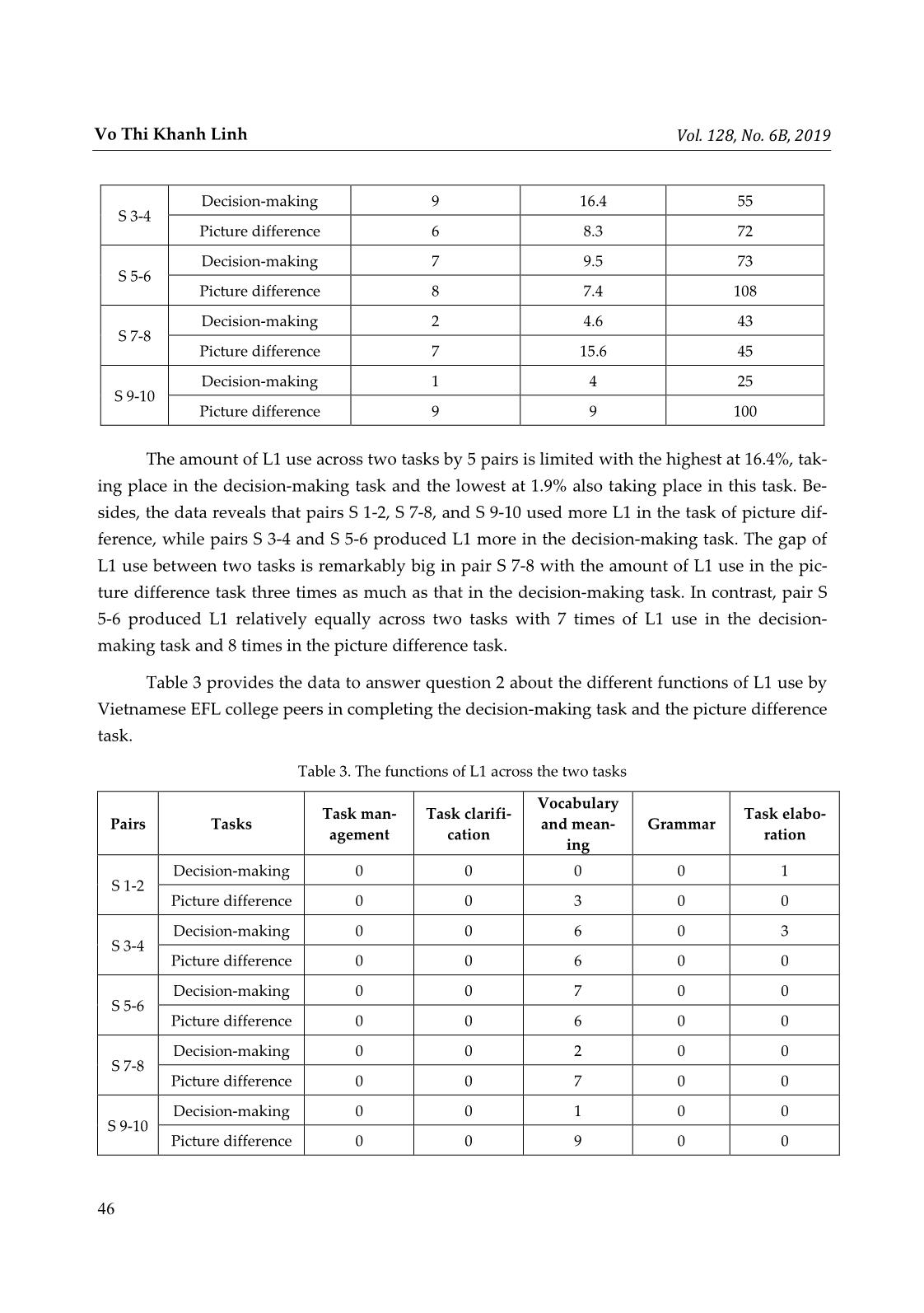

d the correct name of the game; as a result, S7 is able to use the right word although it is in Vietnamese. Thus, it can be argued that a peer (S8) is able to provide his/her peer with an opportunity for learning [Watanabe, 2008; Storch, 2002]by using L1. 5. Discussion and implications First, the data revealed a small amount of L1 use during the two task completions with a higher percentage of 16.4% in the decision-making task. Thismoderate use of L1is in line with that of Storch and Wigglesworth [2003]although this figure is much smaller. The fact that the students’ high proficiency level can result in the small amount of L1 use is reportedin various studies on the association of learners’ proficiency with the amount of L1 use [Bao & Du, 2015; DiCamilla & Antón, 2012; Swain & Lapkin, 2000;Storch & Aldosari, 2010]. Unlike Bao and Du’s (2015) participants of beginner-level lower-secondary school learners, the participants in the current study are college students at the intermediate level in a highly demanding academic context similar to that of Storch and Wigglesworth [2003]. This similarity favours the facts of the shared findings of two studies in which students used a smaller amount of L1 during task com- pletion. Moreover, the ten-minute preparation can also provide students enough time for recal- ling the words they forgot and checking the unknown words in dictionaries, which significantly reduces the amount of L1. It is to say that language teachers should be aware of the necessity and benefits of L1 in the L2 learning process and accept their learners’ using L1 in classroom Vo Thi Khanh Linh Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 50 contexts and during peer interaction. Teachers in language classrooms might need to think of providing enough time for preparation for linguistic achievements and learning success. Second, participants use L1 mainly to assist their partners in finding the words they do not know or remember, clarifying unclear vocabulary, searching for unknown vocabulary, mak- ing explanations, and translating. The high-proficient learners in this study used L2 instead of L1 for the task management or task clarification, whilst the use of L1 was mainly for discussing vocabulary searches. The results are in line with the findingsin DiCamilla and Antón’s[2012]study. In fact, the meaning-focused nature of the tasks might result in the predo- minant function of L1 for vocabulary and meaning. Moreover, participants used L1 to elaborate on the ideas for their peers’ arguments. The mediational functions of L1 have been restricted in two categories of vocabulary and meaning and task elaboration. The range of L1 functions used by intermediate level learners are smaller than that used by elementary level learners because thehigher language abilities of the former result in lower needs of L1 in producing the grammar and explaining the task or finding the unknown words. Obviously, students with higher lan- guage proficiency seem highly reluctant to use their L1 even when allowed to do so [Storch & Wigglesworth, 2003]. The findings provide pedagogical implications for language teaching and learning in term of teachers’ concerns about their intermediate-level students’ using L1 in pair work or group work when teachers arenot always involved in their task completion. Moreover, language teachers should pay attention to the way of pairing students with different proficiency to maximise the scaffolding chances and mediational role of L1. Third, L1 promotes language learning in peer interaction. With the use of L1, learners can make use of their available linguistic resources, relate their understanding of existing know- ledge and identify the gaps between their current language and the target language, all of which are the prerequisite conditions for development. A large amount of evidence across two tasks by 5 pairs illustrates the mediational role of L1 use in language learning. The interactive conversations on decision-making and knowledge-building meanings between two participants can last longerwith the use of L1 to mediate the understanding in peer interaction. It is to say that L1 use smoothens the language learners’ path and then promotes EFL learning. These re- sults are consistent with those reported by Algería de la Colina and García Mayo [2009], Bao and Du [2015]and Bhooth, Azman and Ismail [2014]. The findings show that the amount of L1 use is different from pair to pair and from task to task. In essence,task types provide greater impact on the amount of L1 use [Alegría de la Co- lina & García Mayo, 2009; Azkarai & García Mayo, 2015; Storch & Aldosari, 2010; Storch & Wigglesworth, 2003]and have a closerelationship with L1 functions [Alegría de la Colina & Gar- cía Mayo, 2009; Storch & Wigglesworth, 2003]. Similarly, the results are in line with the pre- vious findings, which revealthat participants made more use of their shared L1 in the picture Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 51 difference task (31 turns) than in the decision-making task(20 turns).Specifically, the surpassing amount of L1 use for vocabulary and meaning in the picture difference task with all 31 turns significantly indicates the influence of task types on the L1 use in peer interaction. The tasks per se, then, also serve as mediators of L2 learning, which provide the context for collaborative di- alogues with the meaning of decision-making and knowledge-building dialogue with support evidence from Swain [1997, cited in Swain, 2000]and Swain and Lapkin [1998, cited in Swain, 2000]. However, further studies on the association of task types and L1 functions in EFL and peer interaction pattern in relation to L1 use may widen more understanding about the poten- tially valuable role of L1 in language learning. 6. Conclusion The current study shows that, in this case, the Vietnamese language could be used as a mediational tool in language learning in terms of vocabulary and meaning, and task elabora- tion. The amount of L1 use is strictly related to the language learners’ proficiency. The L1 use is inversely proportional to the learners’ proficiency, i.e., the student's proficiency in the target language increases, the dependence on L1 decreases. Last but not least, L1 serves as a media- tional tool to promote the target language learning in peer interaction. However, some limita- tions are also noted due to the smallscale with arestricted number of participants. The fact that L1 use and its functions during speaking-task completion in the Vietnamese context of tertiary level are the main focus leaves some unansweredquestions on the association of L1 and certain task types. Therefore, more research should be conducted to clarify the influence of task natures and task types, namely the decision-making task and picture difference task, on L1 use and its functions. Moreover, the new L1 function of task elaboration leaves a gap for more research to bridge. References 1. Alegría de la Colina, A., & García Mayo, M. (2009), Oral interaction in task-based EFL learning: The use of the L1 as a cognitive tool. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 47(1), 325–345. 2. Anton, M. & DiCamilla, F. (1998), Socio-cognitive functions of L1 collaborative interaction in the L2 classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 54, 314–42. 3. Atkinson, D. 1987. The mother tongue in the classroom: A neglected source? ELT Journal, 41(4), 241–247. 4. Azkarai, A., & García Mayo, M. D. P. (2015), Task-modality and L1 use in EFL oral interaction. Language Teaching Research, 19(5), 550–571. doi:10.1177/1362168814541717 Vo Thi Khanh Linh Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 52 5. Bao, R. and Du, X. (2015), Learners’ L1 use in a task-based classroom: Learning Chinese as aforeign language from a sociocultural perspective. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 6(1), pp. 12–20. Retrieved on Jan 16, 2017,from 6. Bhooth, A., Azman, H., Ismail, K. (2014), The role of the L1 as a scaffolding tool in the EFL reading classroom. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 118 (2014) 76 – 84. Retrieved on November 2, 2017, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042814015419 7. Brooks, Frank B., and Richard Donato (1994), Vygotskyan approaches to understanding foreign language learner discourse during communicative tasks. Hispania,77, 262–274. 8. BuiPhu Hung and NguyenThi Tuyet Anh (2014), The use of Vietnamese in English language classes-benefits and drawbacks. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL), 2(12), December 2014, PP 24–26. Retrieved on April 8, 2017,fromhttps://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijsell/v2-i12/4.pdf 9. Cook, V. (2001), Using the first language in the classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review/La Re- vue Canadienne des langues vivantes,57(3), 402–423. 10. Daniels, H. (2015), Mediation: An expansion of the socio-cultural gaze. History of the Human Sciences, 28(2), 34–50. 11. DiCamilla, F.J., & Antón, M. (2012), Functions of L1 in the collaborative interaction of beginning and advanced second language learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 22, 160–188. 12. Donato, R. (1994), Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J. P. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian Approach to Second Language Research (pp. 33–56). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation. 13. Ellis, R. (2003),Task-based Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 14. Gass, S. M., Mackey, A. & Ross-Feldman, L. (2005), Task-based interactions in classroom and la- boratory settings. Language Learning,55(4),pp. 575–611. 15. Harun, H., Massari, N., Behak, F.P. (2014), Use of L1 as a mediational tool for understanding tense/aspect marking in English: An application of Concept-Based Instruction. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 134, 134–139. Retrieved on April 7, 2018 fromhttps://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042814031413 16. Kieu Hang Kim Anh (2010), Use of Vietnamese in English language teaching in Vietnam: Attitudes of Vietnamese university teachers. English Language Teaching, 3(2). Retrieved on April 8, 2018, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1081650.pdf 17. Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2006),Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 18. Le Pham Hoai Huong (2003), The mediational role of language teachers in sociocultural theory. English Teaching Forum, 1(41),31–35. Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 53 19. Pica, T., Kanagy, R. and Falodun, J. (1993), Choosing and using communication tasks for second language instruction and research. In G. Crookes and S. Gass (Eds.), Tasks and language learning: In- tegrating theory and practice (pp. 9–34). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. 20. Storch, N. (2002), Patterns of interaction in ESL pair work. Language Learning, 52, 119–158. 21. Storch, N. & Aldosari, A. (2010), Learners’ use of first language (Arabic) in pair work in an EFL class. Language Teaching Research, 14(4), 355–375. 22. Storch, N. & Wigglesworth, G. (2003), Is there a role for the use of the L1 in an L2 setting? TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 760–769. Retrieved on April 10, 2018, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228007278 23. Swain, M. & Lapkin, S. (2000), Task-based second language learning: The uses of the first language. Language Teaching Research 4(3), 251–274. 24. Swain, M. (2000), The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. J. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning(pp. 97–113). Oxford University Press. 25. Swain, M. (2006), Languaging, agency and collaboration in advanced language proficiency. In H. Byrnes (Eds.), Advanced language learning: The contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp.95–108). Lon- don: Continuum. 26. Swain, M. & Lapkin, S. (1998), Interaction and second language learning: Two adolescent French immersion students working together. Modern Language Journal, 82, 320–337. 27. Swain, M., Lapkin, D., Knouzi, I., Suzuki, W. & Brooks, L. (2009), Languaging: University students learn the grammatical concept of voice in French. The Modern Language Journal, 93(1), 5–29. 28. Tang, J. (2002), Using L1 in the English classroom. English Teaching Forum, 40(1). Retrieved on April 9, 2018, from https://americanenglish.state.gov/files/ae/resource_files/02-40-1-h.pdf 29. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978),Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 30. Watanabe, Y. (2008),Peer-peer interaction between L2 learners of different proficiency levels: Their interactions and reflections.Canadian modern language review, 64(4), 605–635. 31. Wells, G. (1999), Using L1 to master L2: Aresponse to Anton and DiCamilla's socio-cognitive func- tions of L1 collaborative interaction in the L2 classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 83(2), 248– 254. 32. Wertsch, J. (1991),Voices of the mind: A sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, MA: Har- vard University Press. 33. Yaghobian, F., Samuel, M., Mahmoudi, M. (2017), Learner’s use of first language in EFL collabora- tive learning: Asociocultural view. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 5(4), 35–55. Vo Thi Khanh Linh Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 54 Appendix A Instruction: Look at the park below. Working with a partner, you must describe your picture and find out eight differences. You have 10 minutes to plan what and how to say. However, you are only al- lowed to talk without your notes. Spot the differences park scene. Communicative Tasks (1995). National Languages and Literacy Institute of Australia, Language Acquisition Research Centre, University of Sydney. © National Languages and Literacy Institute of Australia (NLLIA). Appendix B THE DESERT ISLAND You are on a sinking ship. There is only one lifeboat left for your rescue. The boat can only hold a limited amount of supplies and people. You can see a small desert island in the distance. If your boat makes it there safely, you will need things to help you survive until you are rescued. Instruction: Look at the following list of items that you have. Choose only five items that you will bring with you. Working with a partner, you must decide and agree mutually on which five items to take. Jos.hueuni.edu.vn Vol. 128, No. 6B, 2019 55 You have 10 minutes to plan what and how to say. However, you are only allowed to talk without your notes. Items Tick (√) to indicate your choice 1. Torchlight 2. Pillows 3. Canned food 4. Clothes 5. Fresh water 6. Knives 7. Map 8. Family documents 9. Handphone 10. First-aid kit 11. Matches 12. Gun

File đính kèm:

first_language_l1_as_a_mediational_tool_in_peer_interaction.pdf

first_language_l1_as_a_mediational_tool_in_peer_interaction.pdf