Educational improvement: Insights from policy, research and practice in the new zealand context, and implications for teacher education

Educational reform and change relating to curriculum, pedagogy, standards, evaluation and professional learning have an important role to play in educational improvement initiatives. In this paper, I explore insights from policy, research and practice initiatives across key aspects of the New Zealand education landscape, relate those to improvement efforts internationally, and highlight implications and possibilities for teacher education. In particular, the focus is on curriculum reform, inquiry oriented practice, and collaborative inquiry-Key: Elements of those policy turns are outlined, and consideration given to the implications for initial teacher education

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Educational improvement: Insights from policy, research and practice in the new zealand context, and implications for teacher education

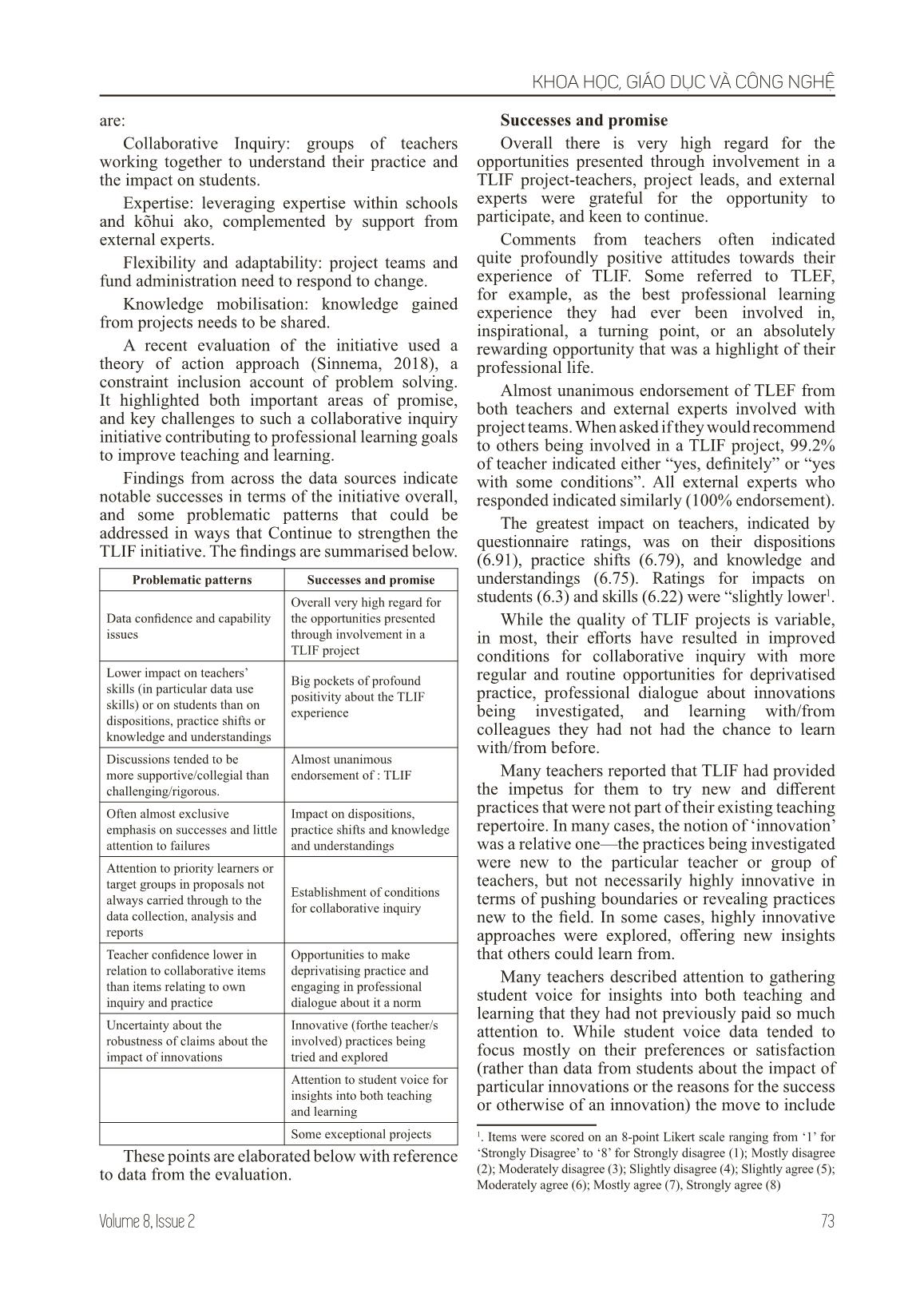

t innovations being investigated, and learning with/from colleagues they had not had the chance to learn with/from before. Many teachers reported that TLIF had provided the impetus for them to try new and different practices that were not part of their existing teaching repertoire. In many cases, the notion of ‘innovation’ was a relative one—the practices being investigated were new to the particular teacher or group of teachers, but not necessarily highly innovative in terms of pushing boundaries or revealing practices new to the field. In some cases, highly innovative approaches were explored, offering new insights that others could learn from. Many teachers described attention to gathering student voice for insights into both teaching and learning that they had not previously paid so much attention to. While student voice data tended to focus mostly on their preferences or satisfaction (rather than data from students about the impact of particular innovations or the reasons for the success or otherwise of an innovation) the move to include 1. Items were scored on an 8-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1’ for ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘8’ for Strongly disagree (1); Mostly disagree (2); Moderately disagree (3); Slightly disagree (4); Slightly agree (5); Moderately agree (6); Mostly agree (7), Strongly agree (8) KHOA HỌC, GIÁO DỤC VÀ CÔNG NGHỆ 74 JOURNAL OF ETHNIC MINORITIES RESEARCH data from students is commendable. The TLIF initiative has revealed some project teams with considerable expertise in leading and carrying out inquiries, learning about the impact of innovations, and mobilising knowledge from their inquiries in a way that is relevant to others. These exceptional projects provide a resource for others, and a basis for sharing not only innovative teaching/classroom practices likely to be effective, but productive processes for collaborative inquiry. Problematic patterns Data confidence and capability stands out as the biggest issue facing teachers, teams and those supporting them. Teachers themselves reported much lower confidence in. their own ability to analyse data in ways that give important insights (6.18), than other aspects of their inquiry work. Those issues were also evident project reports where the quality of the data collected was often questionable, with typically generic descriptions of analyses and generality in claims about impact and causality. For example, claims like this one-“Overall the inquiry... has resulted in the uplifting of student achievement, particularly for our target students, and the teaching and learning of our teachers” were often left without evidence to support them, and no indication that data had been collected or analysed in a way that supported the claim of success. As a consequence of the issues regarding data capability, there was often a lack of robustness in the claims able to be made about the impact of innovations on learners and uncertainty about what knowledge could be mobilised to others. Overall, teachers reported lower impact on their skills (in particular data use skills) (6.22) or on students (6.30) than on dispositions (6.91), practice shifts (6.79) or knowledge and understandings (6.75). Discussions tended to be more supportive (7.55) or collegial (7.50) than challenging (7.17) or rigorous (7.10). That finding is important since we found a robust positive relationship between the quality of project discussions (including rigour and challenge) and impact of TLIF. That is, the better teachers rated their project discussions, the stronger they perceived the impact of the project on their knowledge (r = 0.75**), dispositions (r = 0.64**), practice shifts (r = 0.67**), skills (r = 0.55**) and on students (r = 0.59**). The finding that there was often an almost exclusive emphasis on success and very much less attention to any failures is problematic given the likelihood of failures being associated with innovation, the importance of attention to failure and its causes to puzzles of practice, and the role of fallibility and open mindedness as disposition^ conducive to high quality inquiry. Attention to priority learners or target groups evident in proposals was nó| always carried through to the data, data analysis and reports. Teacher confidence lower in relation to items about ability to collaborate witlf (and influence) other than items relating to own inquiry and practice. Uncertainty about the robustness of claims about the impact of innovations! Most claims were quite general-they referred to increased achievement of student! without specifying which students were impacted, in what ways, or how much theif learning improved, and without sufficient supporting evidence. Some projects we| further, and specified details of which students improved, how and how much. But, v<n few provided robust explained claims where there was, in addition, clear, logical atg evidence-based explanations about how the innovation was related to improvements. Characteristics of Effective TLIF Projects Insights from the various data sources suggest that the following characteristics are associated with more effective TLIF projects. By effective, I refer to the TLIF purposes of a positive impact on outcomes for teachers (their knowledge and understanding, skills, dispositions and practice), for students (their learning experiences, relationships, and achievement), and the generation of new knowledge, understandings and learning that can be mobilised to others. These characteristics both increase the likelihood that innovations teams tty are successful and, equally important, the likelihood that teams will determine, in a timely manner, when and why they are not successful where that is the case. The characteristics are: Unrelenting commitment to and focus on improvement-improvement of both teaching and learning; Levels of risk-taking and innovation appropriate to the capacity of the teachers and contexts involved; High quality collaboration-well-established collaboration routines and norms, that are regular, involve deprivatised practice and occur over an extended duration; High quality data and data analysis relevant to the logic of the innovation; High quality discussion—supportive and collegial and simultaneously challenging and rigorous; High quality expertise from internal sources (teacher leadership) and external sources (relevant quality research, and external experts whose expertise aligns with team needs). Enablers and barriers The extent to which project teams were able to carry out high quality inquiries into their innovation was influenced by a range of barriers and enablers, KHOA HỌC, GIÁO DỤC VÀ CÔNG NGHỆ 75Volume 8, Issue 2 summarised below: Barriers Enablers Logistics and project administration (including time, release issues, personnel changes) Collaboration time Resistance Inquiry orientation Data capability Knowledge-building opportunities Reporting demands Contribution of external expertise Leadership support Summary of Key Messages With a focus on the purpose of the TLIF evaluation to inform continuous improvement of TLIF’s design, implementation and monitoring, the following figure presents a summary of key messages, the current ‘story’ of TLIF as it were. These messages, derived from the evaluation evidence are key because, if attended to, they hold much promise for next steps in improving the initiative overall. Some of these messages represent problems to be solved, but there are strong grounds and good conditions for solving them, given the widespread endorsement of and regard for TLIF, the establishment (or strengthening) of relational conditions conducive to inquiry and innovation, and the presence of some exceptional projects to learn from. Implications for initial teacher education Curriculum, inquiry and collaboration initiatives of the sort outlined above bring with them important considerations for initial teacher education Where such initiatives prompt new and different roles for teachers, they also prompt new and different emphases and approaches for initial teacher education. In the New Zealand context, this has led to calls for a quite new emphasis for the accreditation of initial teacher educator providers, one that makes more prominent attention to the quality of assessments of graduating teacher capability than to the inputs of teacher education programmes. The capabilities required of teachers working with curricula that promote responsive pedagogies, student agency, competencies and partnership require not only different knowledge, but different skills, attitudes and values of those who are being prepared to teach such curricula. Similarly, systems that promote teacher inquiry, and particularly those that promote collaborative inquiry need to pay attention not only to the vast potential of such approaches, but the quite particular demands such approaches have on the capabilities of teachers, including the capabilities to work in and strengthen social networks, and to interact effectively with others in ways that solve problems of practice and generate through rigorous inquiry, deep understandings about the priorities for learners, the approaches most likely to address those priorities and the impact of teaching on learning. Such demands have implications not only for the content of initial teacher education, but the processes involved in programme design, teaching, learning, practicum and assessment. References Aitken, G. & Sinnema, c. (2008). Effective pedagogy in social sciences/Tikanga à iwi: best evidence synthesis iteration. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Anthony, G. & Walshaw, M. (2007). Effective pedagogy in mathematics/p’angarau: best evidence synthesis iteration. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Berliner, D. (1987). Simple views of effective teaching and a simple theory of classroom instruction. In D. Berliner & B. Rosenshine (eds), Talks to teachers (pp. 93-110) New York: Random House. Berliner, D. (2004). Toiling in Pasteur’s quadrant: the contributions of N.L. Gage to educational psychology.Teaching and Teacher Education, 20, pp. 329-340. Carr, M., & Claxton, G. (2002), Tracking the development of learning dispositions. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 9(1), 9 - 37. Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). The new teacher education: For better or worse? Educational Researcher, 34(7), 3-17. Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, s. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. New York: Teachers College Press. Cowie, B., & Hipkins, R. (2009). Curriculum Implementation Exploratory Studies: Final Report.[on-line]available. educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ curriculum/57760/1. Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). ‘What is agency?’. American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962-1023. Hk Fowler, M. (2012). Leading inquiry at a teacher level: it’s all about mentorship. SET, 3, pp. 2-7. . Furman, c. (2018). “Descriptive inquiry: cultivating practical wisdom with teachers.” Teachers and Teaching: 1-12. KHOA HỌC, GIÁO DỤC VÀ CÔNG NGHỆ 76 JOURNAL OF ETHNIC MINORITIES RESEARCH Hart R. A. (1996). Children’s participation: from tokenism to citizenship. In H. Shier (Ed.), Giving children a voice: Camden Social Services. Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: a synthesis of over 800 meta- analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge. Marzano R., Pickering, D. & Pollock, J. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: research- based strategies for increasing student achievement. Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Ministry of Education (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media. Mourshed, M., Chijioke, c., & Barber, M. (2010). How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better. CA: McKinsey & Company Reid, A. (2006). Key competencies: A new way forward or more of the same? Curriculum Matters, 2, 43-62. Robinson, V., Hohepa, M., & Lloyd, c. (2008). School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why. Best evidence synthesis iteration Wellington: Ministry of Education. [on-line] available educationcounts.govt.nz/goto/BES Shier, H. (2001). Pathways to participation: Opening, opportunities and obligations. Children & Society 15(2), 107-117. Shier, H. (2010). Children as public actors: Navigating the tensions. Children & Society 24(1), 24-37. Shulman, L. s. (1987). The wisdom of practice: managing complexity in medicine and teaching. In D. Berliner & B. Rosenshine (eds), Talks to teachers (pp. 249-i 271). New York: Random House. Sinnema, c., Aitken, G., & Meyer, F. (2017). Capturing the Complex, Context- bound and Active Nature of Teaching through Inquiry- oriented Graduating Teachers Standards. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(1), 9-27. Sinnema, c. E., & Aitken, G. (2012). Effective pedagogy in social sciences. In; Sinnema, c. & Aitken, G.(2011). Teaching as inquiry in the New Zealan curriculum: origins and implementation. In J. Parr, H. Hedges & s. May (eds) Changing trajectories of teaching and learning (pp. 29-48). Wellington: NZCER. Sinnema, c. (2011). Monitoring and evaluating curriculum implementation. Final evaluation report on the implementation of the New Zealand curriculum 2008¬2009. Wellington: The Ministry of Education. CẢI CÁCH GIÁO DỤC: NHỮNG HIỂU BIẾT TỪ CHÍNH SÁCH, NGHIÊN CỨU ĐẾN THỰC HÀNH TRONG BỐI CẢNH GIÁO DỤC TẠI NEW ZEALAND VÀ ẢNH HƯỞNG ĐỐI VỚI VIỆC ĐÀO TẠO GIÁO VIÊN Claire Sinnema Đại học Auckland, New Zealand Email: c.sinnema@auckland.ac.nz Ngày nhận bài: 4/5/2019 Ngày phản biện: 8/5/2019 Ngày tác giả sửa: 25/5/2019 Ngày duyệt đăng: 12/6/2019 Ngày phát hành: 21/6/2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.25073/0866-773X/303 Tóm tắt: Cải cách giáo dục và những thay đổi liên quan đến chương trình giảng dạy, phương pháp sư phạm, tiêu chuẩn, đánh giá và giáo dục nghề nghiệp có vai trò quan trọng trong các sáng kiến cải tiến giáo dục. Trong bài viết này, tôi tìm hiểu từ các sáng kiến về chính sách, nghiên cứu và thực hành trên các khía cạnh chủ yếu của giáo dục New Zealand, cải thiện những nỗ lực quốc tế để nêu bật ý nghĩa và khả năng đào tạo giáo viên. Đặc biệt, trọng tâm là cải cách chương trình học, thực hành theo hướng điều tra hợp tác: Các thành tố của chính sách này đã được phác thảo và xem xét để đưa ra các hàm ý cho giáo dục ban đầu của giáo viên. Từ khóa: Cách mạng công nghiệp 4.0; Đào tạo giáo viên; New Zealand; Cải cách giáo dục.

File đính kèm:

educational_improvement_insights_from_policy_research_and_pr.pdf

educational_improvement_insights_from_policy_research_and_pr.pdf