A longitudinal study of self-selection, learning-by-exporting and core-competence: The case of smalland medium-sized enterprises in Vietnam

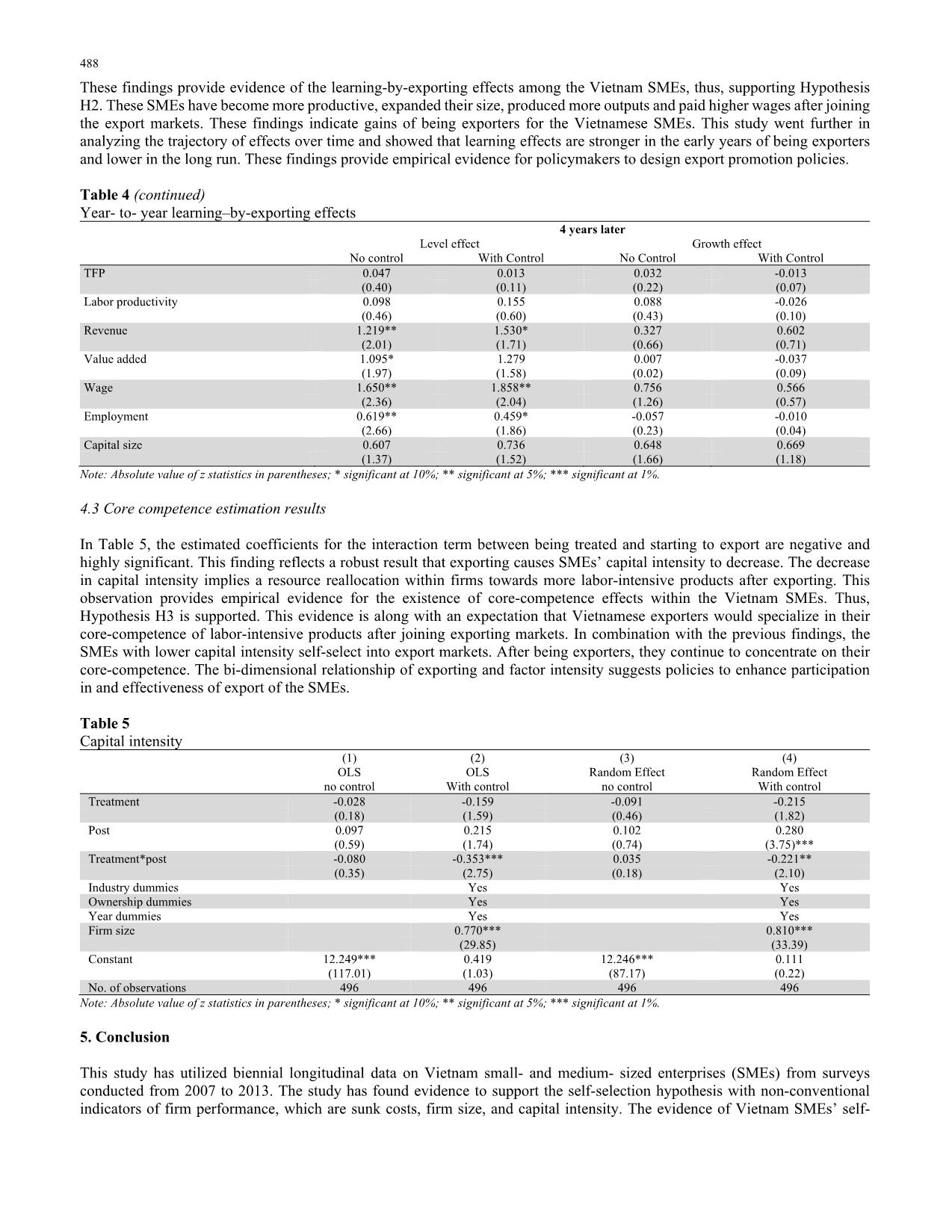

Based on longitudinal data from biennial surveys of small- and medium- sized enterprises (SMEs) in

Vietnam conducted from 2007 to 2013, we find supports to the self-selection and learning-by-exporting

hypotheses. We find that the SMEs having higher sunk costs and capital size are more likely to become

exporters. Applying the propensity score matching method in combination with the Difference-inDifference estimation, the study finds that export has raised SMEs’ productivity measured by either

TFP or labor productivity, sales revenue, and value added of the SMEs. Furthermore, the gains from

learning-by-exporting and specializing in core-competence products were stronger in the early years

of entry into the export markets. These findings suggest policies to promote export of SMEs in an

appropriate timing

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

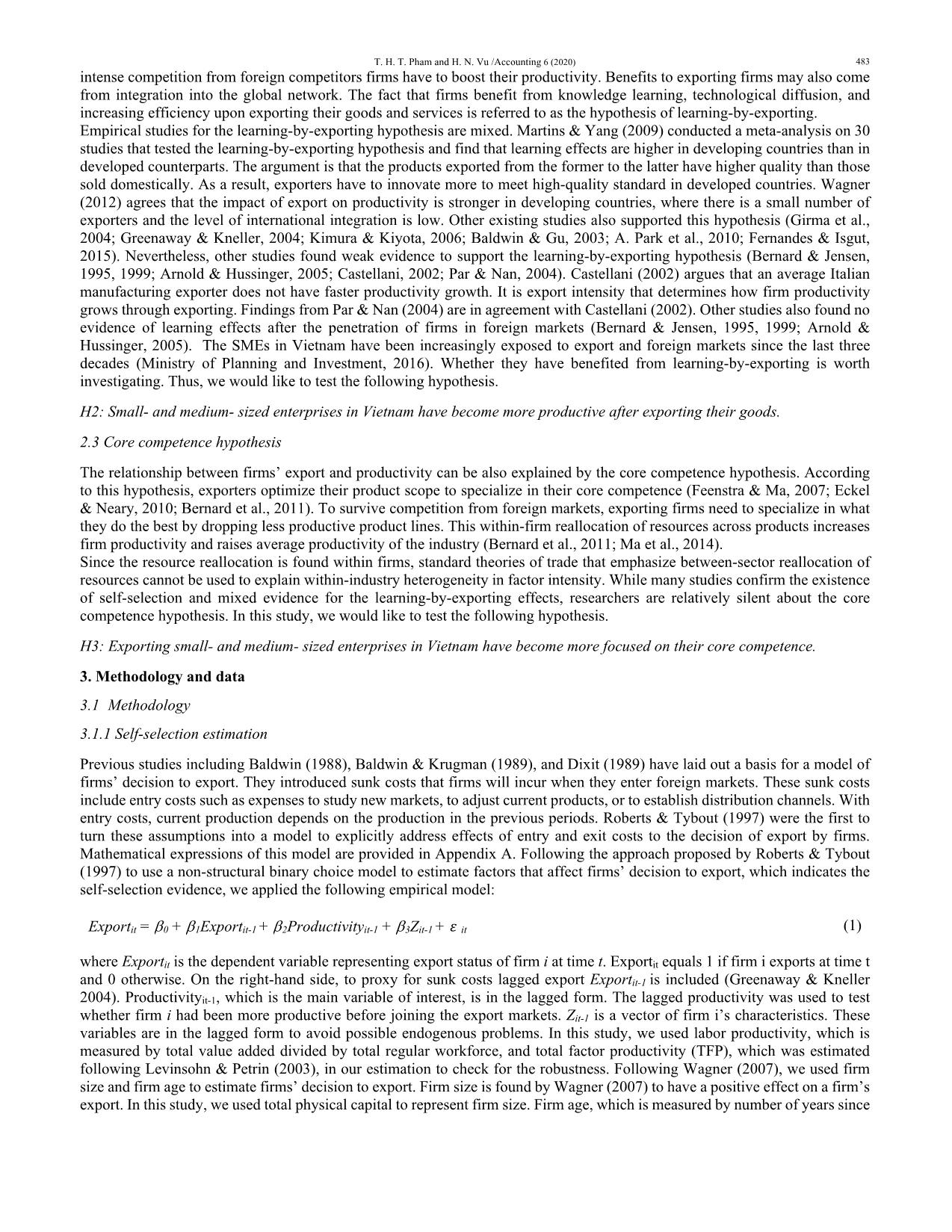

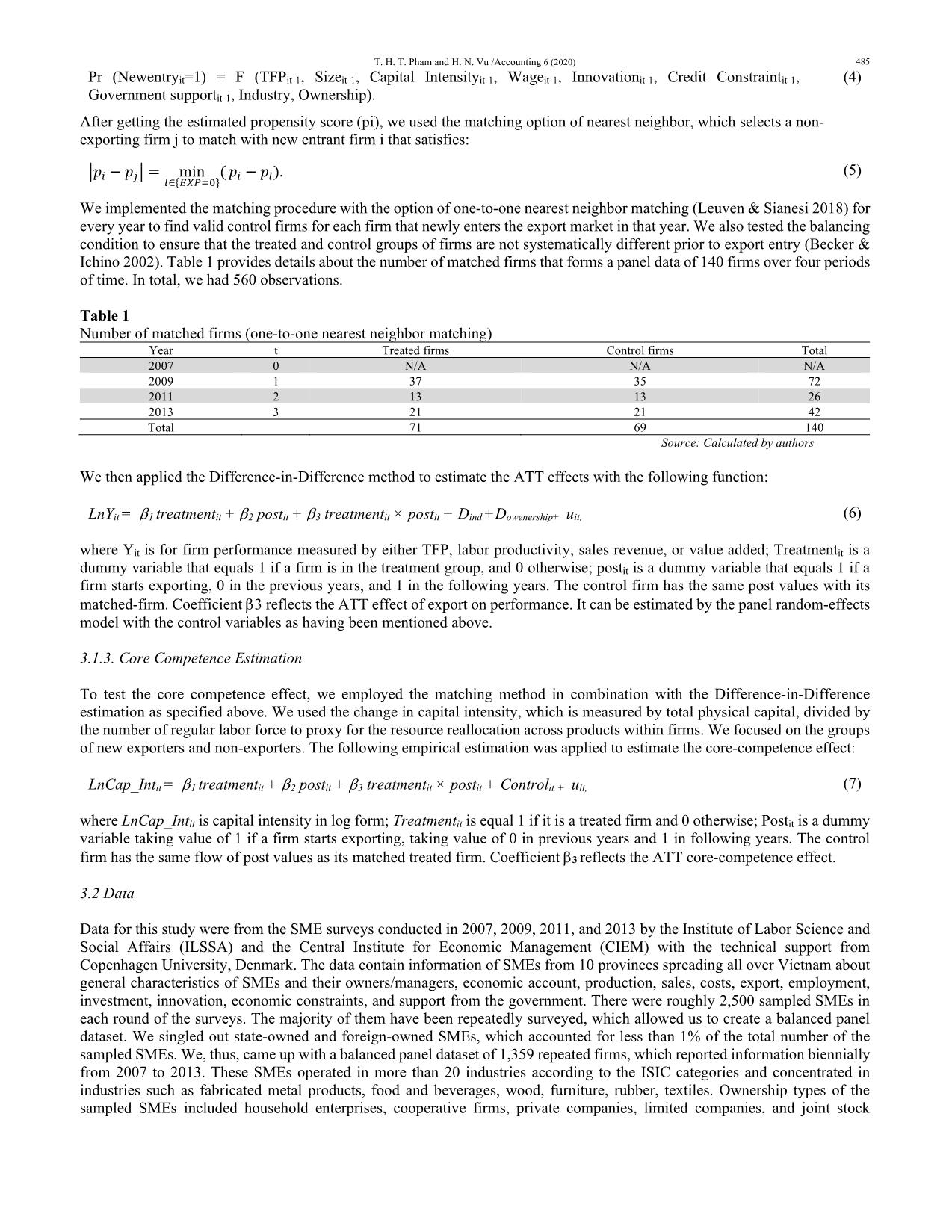

Trang 5

Trang 6

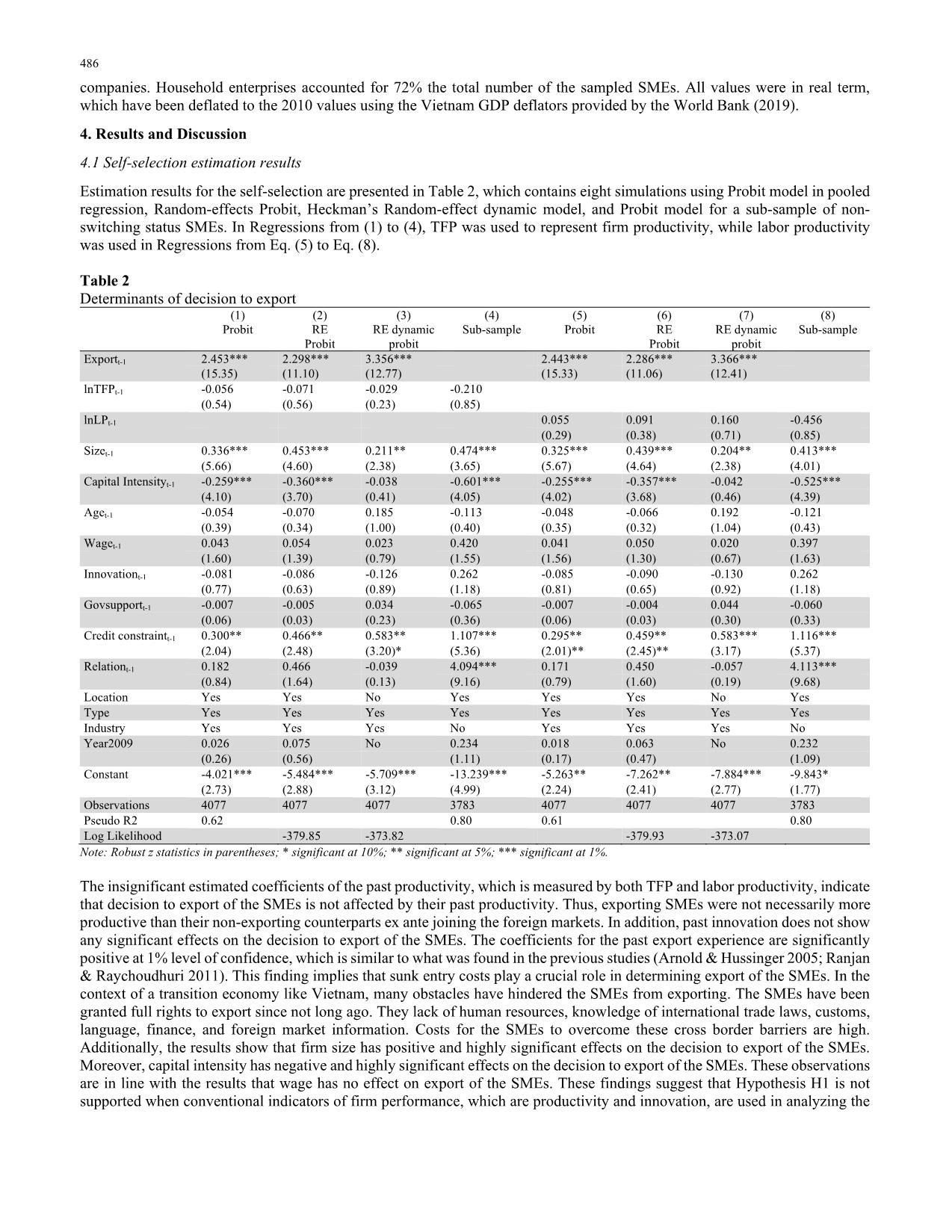

Trang 7

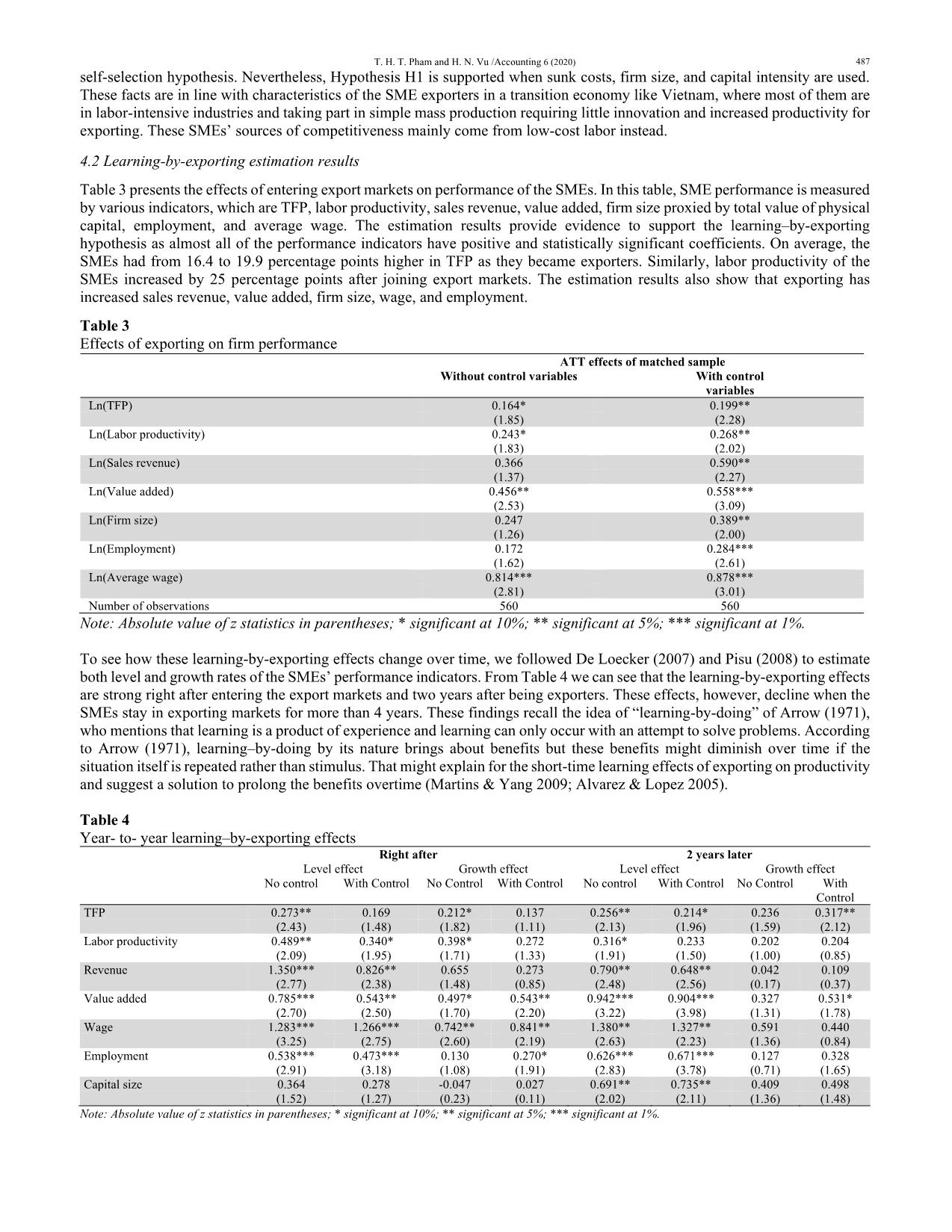

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: A longitudinal study of self-selection, learning-by-exporting and core-competence: The case of smalland medium-sized enterprises in Vietnam

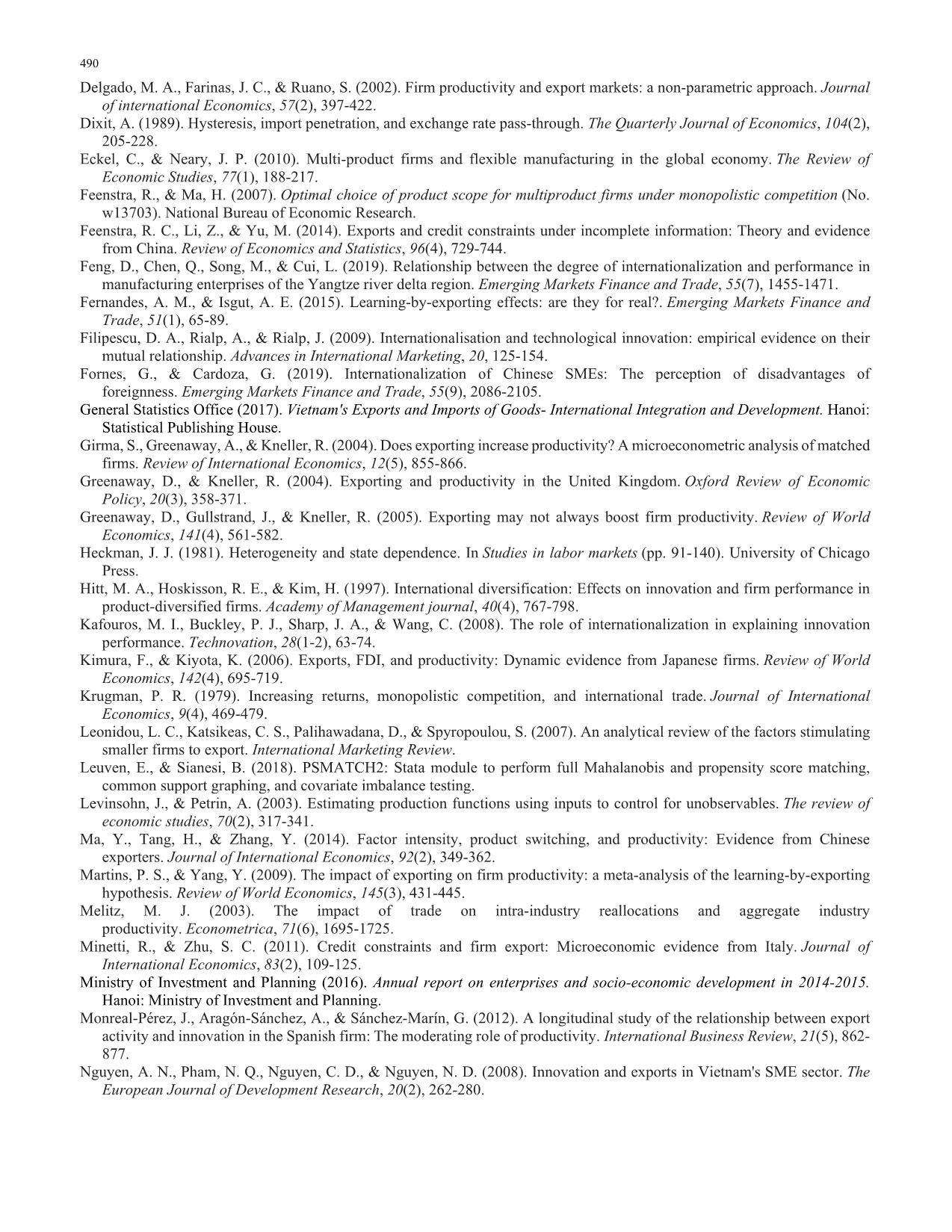

resources towards their core-competence, which are in labor-intensive

products. Participation of the SMEs in exporting has not yet increased Vietnamese SMEs' capital intensity. Instead, the focus of

the SMEs has been still on labor-intensive industries, of which the competitive advantages come from labor abundance and low-

wages in transition economies like Vietnam.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant

number 502.01-2018.03.

References

Alegre, J., & Chiva, R. (2008). Assessing the impact of organizational learning capability on product innovation performance:

An empirical test. Technovation, 28(6), 315-326.

Alvarez, R., & Lopez, R. A. (2005). Exporting and performance: evidence from Chilean plants. Canadian Journal of

Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique, 38(4), 1384-1400.

Arnold, J. M., & Hussinger, K. (2005). Export behavior and firm productivity in German manufacturing: A firm-level

analysis. Review of World Economics, 141(2), 219-243.

Arrow, K. J. (1971). The economic implications of learning by doing. In Readings in the Theory of Growth (pp. 131-149).

Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Aw, B. Y., Chen, X., & Roberts, M. J. (2001). Firm-level evidence on productivity differentials and turnover in Taiwanese

manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics, 66(1), 51-86.

Baldwin, J. R., & Gu, W. (2003). Export‐market participation and productivity performance in Canadian

manufacturing. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique, 36(3), 634-657.

Baldwin, R. (1988). Hysteresis in import prices: the beachhead effect (No. w2545). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Baldwin, R., & Krugman, P. (1989). Persistent trade effects of large exchange rate shocks. The Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 104(4), 635-654.

Becker, S. O., & Ichino, A. (2002). Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. The Stata Journal, 2(4),

358-377.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., & Lawrence, R. Z. (1995). Exporters, jobs, and wages in US manufacturing: 1976-1987. Brookings

papers on economic activity. Microeconomics, 1995, 67-119.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (1999). Exceptional exporter performance: cause, effect, or both?. Journal of international

economics, 47(1), 1-25.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (2004). Why some firms export. Review of economics and Statistics, 86(2), 561-569.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (2004). Exporting and Productivity in the USA. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 20(3), 343-

357.

Bernard, A. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2011). Multiproduct firms and trade liberalization. The Quarterly journal of

economics, 126(3), 1271-1318.

Castellani, D. (2002). Export behavior and productivity growth: Evidence from Italian manufacturing

firms. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 138(4), 605-628.

Clerides, S. K., Lach, S., & Tybout, J. R. (1998). Is learning by exporting important? Micro-dynamic evidence from Colombia,

Mexico, and Morocco. The quarterly journal of economics, 113(3), 903-947.

Doan, N. T., Nguyen, K. T., & Mai, P. C. (2020). The effects of cash in advance on export decision: the case of Vietnam.

Journal of International Economics and Management, 20(1), 1-12.

De Loecker, J. (2007). Do exports generate higher productivity? Evidence from Slovenia. Journal of international

economics, 73(1), 69-98.

490

Delgado, M. A., Farinas, J. C., & Ruano, S. (2002). Firm productivity and export markets: a non-parametric approach. Journal

of international Economics, 57(2), 397-422.

Dixit, A. (1989). Hysteresis, import penetration, and exchange rate pass-through. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(2),

205-228.

Eckel, C., & Neary, J. P. (2010). Multi-product firms and flexible manufacturing in the global economy. The Review of

Economic Studies, 77(1), 188-217.

Feenstra, R., & Ma, H. (2007). Optimal choice of product scope for multiproduct firms under monopolistic competition (No.

w13703). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Feenstra, R. C., Li, Z., & Yu, M. (2014). Exports and credit constraints under incomplete information: Theory and evidence

from China. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(4), 729-744.

Feng, D., Chen, Q., Song, M., & Cui, L. (2019). Relationship between the degree of internationalization and performance in

manufacturing enterprises of the Yangtze river delta region. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 55(7), 1455-1471.

Fernandes, A. M., & Isgut, A. E. (2015). Learning-by-exporting effects: are they for real?. Emerging Markets Finance and

Trade, 51(1), 65-89.

Filipescu, D. A., Rialp, A., & Rialp, J. (2009). Internationalisation and technological innovation: empirical evidence on their

mutual relationship. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 125-154.

Fornes, G., & Cardoza, G. (2019). Internationalization of Chinese SMEs: The perception of disadvantages of

foreignness. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 55(9), 2086-2105.

General Statistics Office (2017). Vietnam's Exports and Imports of Goods- International Integration and Development. Hanoi:

Statistical Publishing House.

Girma, S., Greenaway, A., & Kneller, R. (2004). Does exporting increase productivity? A microeconometric analysis of matched

firms. Review of International Economics, 12(5), 855-866.

Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2004). Exporting and productivity in the United Kingdom. Oxford Review of Economic

Policy, 20(3), 358-371.

Greenaway, D., Gullstrand, J., & Kneller, R. (2005). Exporting may not always boost firm productivity. Review of World

Economics, 141(4), 561-582.

Heckman, J. J. (1981). Heterogeneity and state dependence. In Studies in labor markets (pp. 91-140). University of Chicago

Press.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Kim, H. (1997). International diversification: Effects on innovation and firm performance in

product-diversified firms. Academy of Management journal, 40(4), 767-798.

Kafouros, M. I., Buckley, P. J., Sharp, J. A., & Wang, C. (2008). The role of internationalization in explaining innovation

performance. Technovation, 28(1-2), 63-74.

Kimura, F., & Kiyota, K. (2006). Exports, FDI, and productivity: Dynamic evidence from Japanese firms. Review of World

Economics, 142(4), 695-719.

Krugman, P. R. (1979). Increasing returns, monopolistic competition, and international trade. Journal of International

Economics, 9(4), 469-479.

Leonidou, L. C., Katsikeas, C. S., Palihawadana, D., & Spyropoulou, S. (2007). An analytical review of the factors stimulating

smaller firms to export. International Marketing Review.

Leuven, E., & Sianesi, B. (2018). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching,

common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. The review of

economic studies, 70(2), 317-341.

Ma, Y., Tang, H., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Factor intensity, product switching, and productivity: Evidence from Chinese

exporters. Journal of International Economics, 92(2), 349-362.

Martins, P. S., & Yang, Y. (2009). The impact of exporting on firm productivity: a meta-analysis of the learning-by-exporting

hypothesis. Review of World Economics, 145(3), 431-445.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra‐industry reallocations and aggregate industry

productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695-1725.

Minetti, R., & Zhu, S. C. (2011). Credit constraints and firm export: Microeconomic evidence from Italy. Journal of

International Economics, 83(2), 109-125.

Ministry of Investment and Planning (2016). Annual report on enterprises and socio-economic development in 2014-2015.

Hanoi: Ministry of Investment and Planning.

Monreal-Pérez, J., Aragón-Sánchez, A., & Sánchez-Marín, G. (2012). A longitudinal study of the relationship between export

activity and innovation in the Spanish firm: The moderating role of productivity. International Business Review, 21(5), 862-

877.

Nguyen, A. N., Pham, N. Q., Nguyen, C. D., & Nguyen, N. D. (2008). Innovation and exports in Vietnam's SME sector. The

European Journal of Development Research, 20(2), 262-280.

T. H. T. Pham and H. N. Vu /Accounting 6 (2020) 491

Pär, H., & Nan, L. N. (2004). Exports as an Indicator on or Promoter of Successful Swedish Manufacturing Firms in the

1990s. Review of World Economics, 140(3), 415-445.

Park, A., Yang, D., Shi, X., & Jiang, Y. (2010). Exporting and firm performance: Chinese exporters and the Asian financial

crisis. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 822-842.

Park, B. I. (2011). Knowledge transfer capacity of multinational enterprises and technology acquisition in international joint

ventures. International Business Review, 20(1), 75-87.

Pisu, M. (2008). Export destinations and learning-by-exporting: Evidence from Belgium. National Bank of Belgium working

paper, (140).

Pla-Barber, J., & Alegre, J. (2007). Analysing the link between export intensity, innovation and firm size in a science-based

industry. International Business Review, 16(3), 275-293.

Ranjan, P., & Raychaudhuri, J. (2011). Self‐selection vs learning: evidence from Indian exporting firms. Indian Growth and

Development Review, 4(1), 22-37.

Roberts, M. J., & Tybout, J. R. (1997). The decision to export in Colombia: An empirical model of entry with sunk costs. The

American Economic Review, 545-564.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal

effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41-55.

Silva, A., Afonso, Ó., & Africano, A. P. (2010). Do Portuguese manufacturing firms learn by exporting? (No. 373).

Universidade do Porto, Faculdade de Economia do Porto.

Tomiura, E. (2007). Foreign outsourcing, exporting, and FDI: A productivity comparison at the firm level. Journal of

International Economics, 72(1), 113-127.

VCCI. 2017. Annual Report on Vietnamese Business 2016. Hanoi: Information and Communications Publishing House.

Vu, H., Lim, S., Holmes, M., & Doan, T. (2013). Firm Exporting and Employee Benefits: First Evidence from Vietnam

Manufacturing SMEs. Economics Bulletin, 33(1), 519-535.

Vu, H. N., & Hoang, B. T. (2020). Business environment and innovation persistence: the case of small-and medium-sized

enterprises in Vietnam. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2019.1689597

Wagner, J. (2007). Exports and productivity: A survey of the evidence from firm‐level data. World Economy, 30(1), 60-82.

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: a survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World

Economics, 148(2), 235-267.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource‐based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180.

World Bank (2019). The Wold Bank. Retrieved 06 01, 2017, from data.worldbank.org:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.DEFL.ZS?locations=VN

Appendix A

Bernard and Jensen (1995, 1999, 2004) started with a simple case with one time period and no entry cost, the profit function it

of firm i at time period t is as below:

it (Xt, Zit) = pt . qit* - cit (Xt, Zit| qit*) Eq. (A.1)

where qit* is the optimal quantity produced if a firm exports; cit is the cost of producing quantity qit*; pt is the selling price of goods

in the foreign market; Xt is the vector of exogenous factors that affect production of the firm such as exchange rate, export promotion

regimes; Zit is a vector of all endogenous or firm-specific factors that have influence on profitability such as productivity, size, age,

labor quality, innovation. If an expected profit of exporting is equal to or greater than zero, a firm will export. Otherwise, it

remains serving the domestic market only. Denoting Yit as firm i’s export status at time t, then Yit =1 if it 0 and Yit =0 if

it<0. In the multiple periods case, let represent a single discounting rate, then expected profit of a firm becomes:

it (Xt, Zit) = Et ( )

Eq. (A.2)

As long as the cost function of today production does not depend on production in previous periods, then the expected profit

function in the multi-period case is similar to the single period case. Otherwise, the current export status will have effects on

future export status and the value function of the optimizing problem is as follow:

( it. Yit + . Et [Vit+1(.)|q*it] ) Eq. (A.3)

A firm will export in period t if the following inequality satisfies:

it + . Et[Vit+1 (.) | q*it>0] > . Et[Vit+1 (.) | q*it=0] Eq. (A.4)

s t.[ ps.q*is cis.(Xs, Zis | qis*)]

s t

Vit (.) max{q*it }

492

Entry costs are denoted by N. It is normal to make an assumption that firm will not have to pay entry costs if they had already

exported (i.e. N=0 if Yit-1=1). When making a decision to export, firms understand that if they export today, they might not

have to pay entry costs in the future. In a single-period case with entry costs, a firm’s profit is specified as follows:

Π௧ᇱ (Xt, Zit, q*it-1) = pt . qit* - cit (Xt, Zit, q*it-1| qit*) – N (1-Yit-1) Eq. (A.5)

This means firms do not have to pay entry cost if they exported in the previous periods, i.e. Yit-1=1. Firms will export if expected

profits minus entry costs are positive. It means Yit=1 if Π௧ᇱ >0. In a multi-period case with entry costs, firms choose a sequence

of output levels, , that maximizes current and discounted future profit. It means it = Et ( s-t [Π௦ᇱ .Yis]), where in

the single-period Π௦ᇱ is non-negative as firms have an option of not exporting. With a value function as represented below:

(Π௧ᇱ . [q*it >0]+ . Et [Vit+1(.)|q*it]) Eq. (A.6)

Firm i will export in time t if expected profit net any entry costs is greater than zero as follows:

pt . qit*+ . (Et[Vit+1 (.) | q*it>0] - Et[Vit+1 (.) | q*it=0]) - cit (Xt, Zit, q*it-1| qit*) – N (1-Yit-1) >0 Eq. (A.7)

Or

pt . qit*+ . (Et[Vit+1 (.) | q*it>0] - Et[Vit+1 (.) | q*it=0]) > cit (Xt, Zit, q*it-1| qit*) + N (1-Yit-1) Eq. (A.8)

If we define Π௧∗ = pt . qit*+ . (Et[Vit+1 (.) | q*it>0] - Et[Vit+1 (.) | q*it=0]), the decision to export by firm is given by the

following discrete choice equation:

𝑌௧ = ൜1 𝑖𝑓 Π௧∗ − 𝑐௧ − 𝑁(1 − 𝑌௧ିଵ) 00 𝑜𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑤𝑖𝑠𝑒 Eq. (A.9)

According to Roberts and Tybout (1997), a method of non-structural binary choice can be used to estimate the decision to export

with the following empirical model:

𝑌௧ = ቄ1 𝑖𝑓 𝛽𝑋௧ 𝛾𝑍௧ − 𝑁(1 − 𝑌௧ିଵ) 𝜀௧ 00 𝑜𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑤𝑖𝑠𝑒 Eq. (A.10)

© 2020 by the authors; licensee Growing Science, Canada. This is an open access article distributed

under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license

(

{qit

*}s t

s t

Vit (.) max{q*it }

File đính kèm:

a_longitudinal_study_of_self_selection_learning_by_exporting.pdf

a_longitudinal_study_of_self_selection_learning_by_exporting.pdf