Tìm hiểu niềm tin vào năng lực viết của sinh viên chuyên ngành Tiếng Anh

Niềm tin vào năng lực của bản thân đóng vai trò then chốt trong việc cải thiện quá trình học ngôn

ngữ. Hiểu rõ niềm tin vào năng lực viết của người học ngôn ngữ có thể giúp nâng cao khả năng

viết của họ. Tuy nhiên, niềm tin vào năng lực viết của người học ngôn ngữ ở các ngữ cảnh khác

nhau thì khác nhau. Vì vậy, bài báo này nhằm trình bày nghiên cứu về niềm tin vào năng lực viết

của sinh viên chuyên ngành tiếng Anh của trường Đại học Đà Lạt, thuộc tỉnh Lâm Đồng, Việt

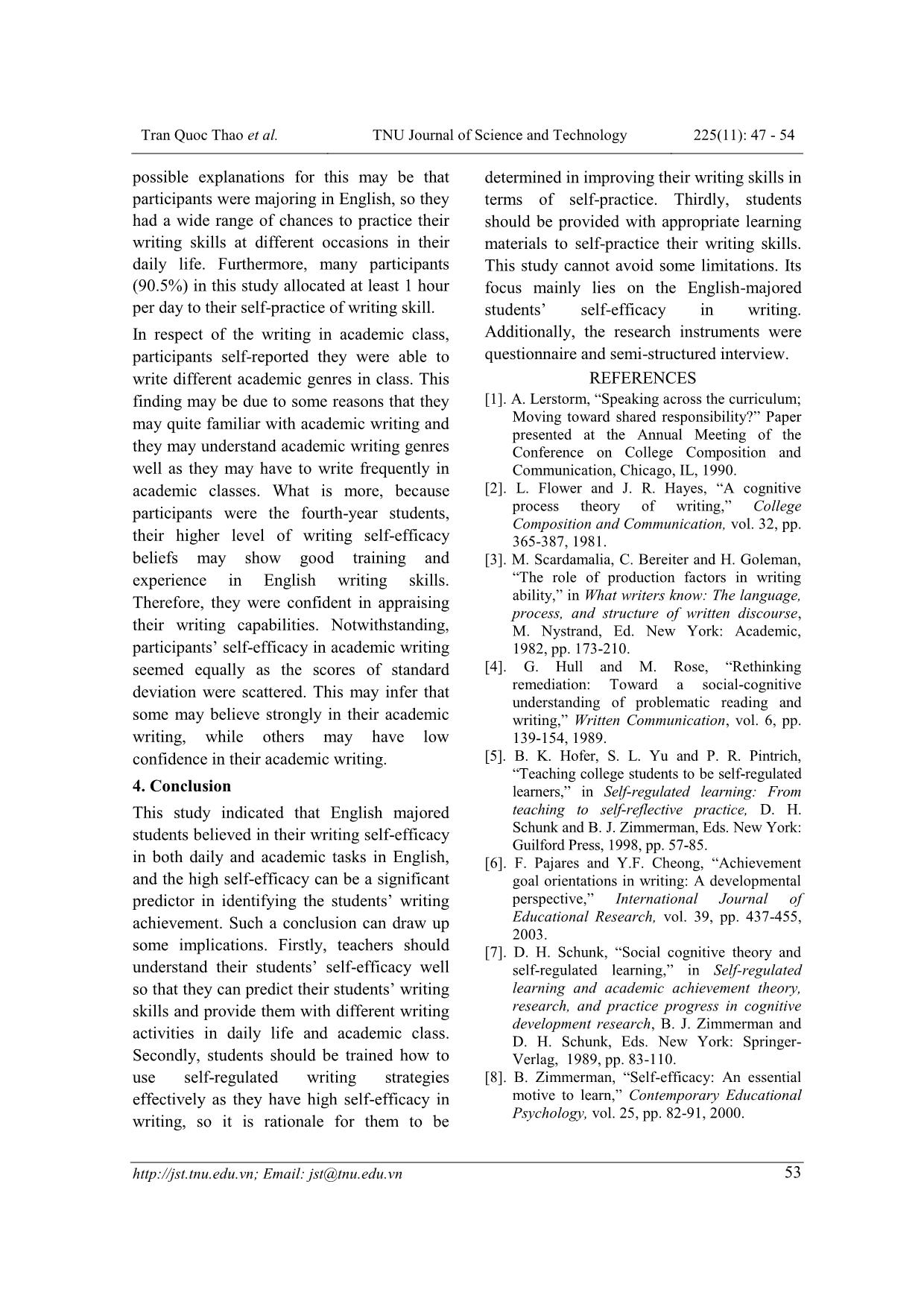

Nam. Nghiên cứu này có sự tham gia của 179 sinh viên năm cuối chuyên ngành tiếng Anh trong

việc trả lời bảng khảo sát và 15 sinh viên tham gia phỏng vấn bán cấu trúc. Dữ liệu định lượng từ

bảng câu hỏi được phân tích bằng SPSS 20.0 về mặt thống kê mô tả, trong khi dữ liệu định tính từ

các cuộc phỏng vấn được phân tích sử dụng phương pháp phân tích nội dung. Kết quả cho thấy

những người tham gia tin rằng họ có thể viết tiếng Anh tốt trong cuộc sống hàng ngày và trong lớp

học. Hơn nữa, những người tham gia cũng thể hiện sự tự tin vào khả năng viết của mình. Những

phát hiện của nghiên cứu này được hy vọng sẽ góp phần hiểu rõ hơn về những sinh viên năm cuối

chuyên ngành tiếng Anh. Như vậy, ý nghĩa sư phạm được đề xuất để cải thiện chất lượng dạy và

học viết học thuật dựa trên các sinh viên chuyên ngành tiếng Anh.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Tìm hiểu niềm tin vào năng lực viết của sinh viên chuyên ngành Tiếng Anh

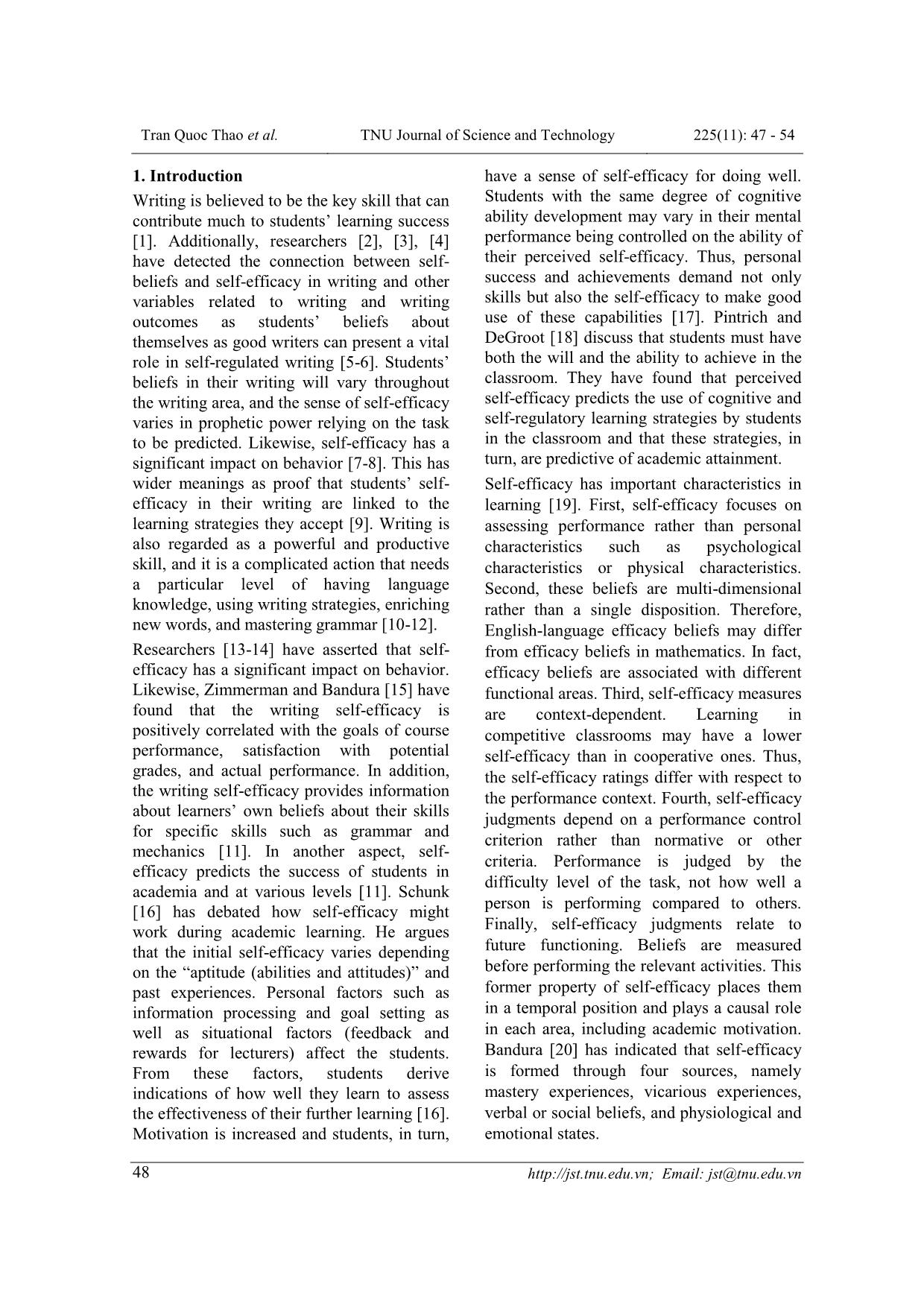

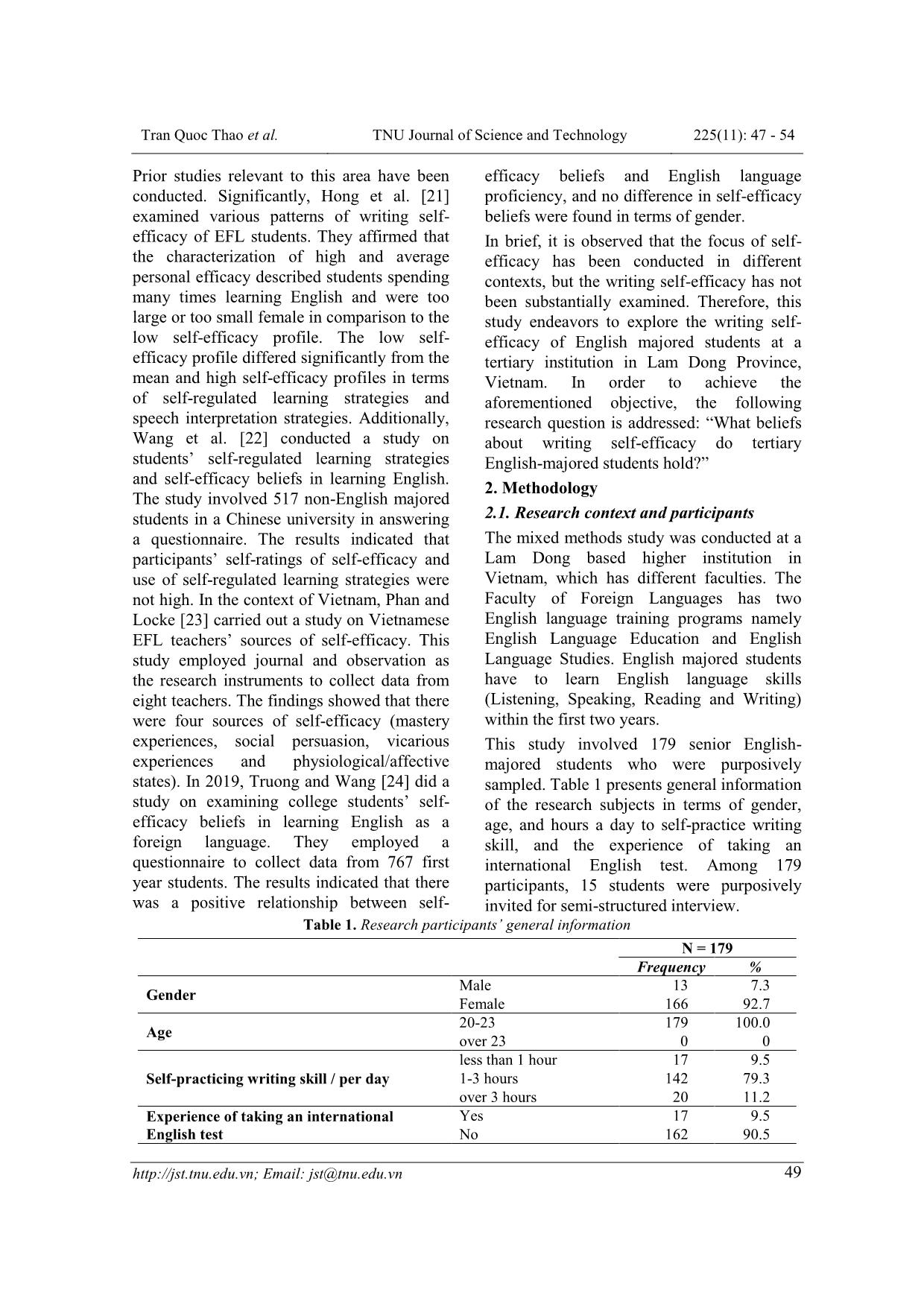

= 4.34; SD =1.01). The scores of standard deviation were very large. It could be understood that participants’ writing self- efficacy in daily life was scattered. Tran Quoc Thao et al. TNU Journal of Science and Technology Email: jst@tnu.edu.vn 51 Table 2. English-majored students’ writing self-efficacy in daily life No Item 225(11): 47 - 54 N=179 M SD 1 I compose messages in English on the Internet (Facebook, Twitter, blogs, etc.) 4.40 .97 2 I write a text in English. 4.34 1.10 3 I leave a note for another student in English. 4.40 .97 4 I write e-mails in English. 4.39 1.00 5 I write diary entries in English. 4.34 1.09 6 I write an invitation to a friend for a party. 4.38 1.01 7 I write a good report. 4.37 1.02 Total 4.37 1.02 Note: M=mean; SD= Standard deviation With respect to the findings from the semi- structured interviews, it was found that interviewees had high writing self-efficacy beliefs in their daily life. They reported that they usually did their writing in English outside a class such as writing letters, writing a diary and joining online discussions. Some particular examples are as follows: I like writing a diary. Not only would this be a keepsake to reflect on many years down the line, but I will be able to practice my writing in English. Set my goals for the week, try to achieve them and then write what I did that week. (S4) I join online discussions to discuss some course- related questions that can help me analyze material, clarify commonalities and differences, and answer other students’ entries. (S10) Moreover, participants shared that they could write in English in daily life because they practiced writing a lot. They could use formal constructions and high-level vocabulary, and they always consulted a good dictionary to choose proper words. In addition, they affirmed that being good at writing meant choosing the right words and not filling the entire page. In a like manner, an interviewee stated that he was confidence in his writing because he could identify and practice the writing of sentences, correct common sentence types, practice the writing of many sentence types as well as avoid some common mistakes. For example, some students described as below: I am good at writing because I can identify and practice writing sentences, recognize and correct common types of sentences, recognize and practice writing many types of sentences as well as avoid some common mistakes. (S6) I am good at writing because I can use formal constructions and high-level vocabulary and always consult a good dictionary to choose the proper word. (S12) 3.1.2 English-majored students’ writing self- efficacy in writing class As illustrated in Table 3 about English- majored students’ writing self-efficacy in writing class, participants were totally able to write “reflections” (item 11: M = 4.39; SD = .97), “long sentences such as compound/complex sentences” (item 12: M = 4.38; SD = .1.00), “messages” (item 9: M = 4.35; SD = 1.05) “in English, “keep writing even when it is difficult” (item 14: M = 4.37; SD = 1.01), and “form new sentences from words [they] have just learnt” (item 14: M = 4.35; SD = 1.07). In addition, participants could “write essays in English” (item 10: M = 3.39; SD = 1.54) and “do writing assignments at the last minute and still get a good grade” (item 13: M = 3.43; SD = 1.17). Nonetheless, they were possibly able to “make English sentences with idiomatic phrases” (item 8: M = 3.31; SD =1.20). Regarding the scores of standard deviation, they are quite large. This means that there were gaps among participants’ answers. Tran Quoc Thao et al. TNU Journal of Science and Technology 225(11): 47 - 54 Email: jst@tnu.edu.vn 52 Table 3. English-majored students’ writing self-efficacy in writing class No Item n=179 M SD 8 I make English sentences with idiomatic phrases. 3.31 1.20 9 I write messages in English. 4.35 1.05 10 I write essays in English. 3.98 1.54 11 I write reflections in English. 4.39 .97 12 I write long sentences such as compound/complex sentences in English. 4.38 1.00 13 I do writing assignments at the last minute and still get a good grade. 3.43 1.17 14 I keep writing even when it is difficult. 4.37 1.01 15 I form new sentences from words I have just learnt. 4.35 1.07 Total 4.07 1.13 Note: M=mean; SD= Standard deviation The findings from the in-depth interviews demonstrated that English-majored students were totally confident in writing in classes because they got good grades on essays that they wrote as well as their lectures helped them to correct their essays. Some particular examples are as follows: the more you practice believing in yourself, the bigger that belief becomes, so I believe in what I have written, and I often get good grades on essays that I wrote. (S9) I practiced writing a lot of essays, and then my lecturers helped me to correct them, so I believe I’m good at writing. (S2) Similarly, some students claimed that they were very confident in writing essays at the university because of their careful preparation and caution. Besides, they could keep writing even when it was difficult. People would be impressed to say that I could write an essay of 2,000 words in less than an hour, but what they don’t know was how much preparation had been done up to that point. Therefore, I am very confident in my essays, and I can keep writing even when it’s difficult. (S5) when I write something down, I use caution to choose the right words. This means that I write more eloquent, concise and elegant, so I can write well. (S14) Moreover, a large number of interviewees predicated that they had never been scared of having their writing evaluated by their peers and marked by their lecturers. I feel less pressured and more relaxed when doing peer review. The useful advice of my peers is easy to use to revise essay, and I am able to do more discussion and practices. (S8) being evaluated by my peers and marked by my lecturers means giving detailed feedback. Therefore, I can improve my grades throughout my educational journey. (S11) 3.2. Discussion This study revealed some major findings. Participants strongly believed that they could write well in English. This finding was not in alignment with that of studies conducted by Hong et al. [21] who have found that their research participants did not have a strong belief in writing self-efficacy. The observed difference is that this study did not examine the correlation between participants’ writing self-efficacy with their writing ability. In addition, this study focused on English- majored students. Therefore, it could be inferred that the frequent practice of writing may contribute to the high self-efficacy in learners, which may positively influence on learners’ self-practice of writing. This is supported by Bandura [20] who have postulated that those with high self-efficacy believe that they can perform well, and he has highlighted that confidence in one’s capacity is a useful predictor of efficiency. With respect to the writing in daily life, participants were strongly confident that they were totally able to write well. One of the Tran Quoc Thao et al. TNU Journal of Science and Technology Email: jst@tnu.edu.vn 53 possible explanations for this may be that participants were majoring in English, so they had a wide range of chances to practice their writing skills at different occasions in their daily life. Furthermore, many participants (90.5%) in this study allocated at least 1 hour per day to their self-practice of writing skill. In respect of the writing in academic class, participants self-reported they were able to write different academic genres in class. This finding may be due to some reasons that they may quite familiar with academic writing and they may understand academic writing genres well as they may have to write frequently in academic classes. What is more, because participants were the fourth-year students, their higher level of writing self-efficacy beliefs may show good training and experience in English writing skills. Therefore, they were confident in appraising their writing capabilities. Notwithstanding, participants’ self-efficacy in academic writing seemed equally as the scores of standard deviation were scattered. This may infer that some may believe strongly in their academic writing, while others may have low confidence in their academic writing. 4. Conclusion This study indicated that English majored students believed in their writing self-efficacy in both daily and academic tasks in English, and the high self-efficacy can be a significant predictor in identifying the students’ writing achievement. Such a conclusion can draw up some implications. Firstly, teachers should understand their students’ self-efficacy well so that they can predict their students’ writing skills and provide them with different writing activities in daily life and academic class. Secondly, students should be trained how to use self-regulated writing strategies effectively as they have high self-efficacy in writing, so it is rationale for them to be 225(11): 47 - 54 determined in improving their writing skills in terms of self-practice. Thirdly, students should be provided with appropriate learning materials to self-practice their writing skills. This study cannot avoid some limitations. Its focus mainly lies on the English-majored students’ self-efficacy in writing. Additionally, the research instruments were questionnaire and semi-structured interview. REFERENCES [1]. A. Lerstorm, “Speaking across the curriculum; Moving toward shared responsibility?” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication, Chicago, IL, 1990. [2]. L. Flower and J. R. Hayes, “A cognitive process theory of writing,” College Composition and Communication, vol. 32, pp. 365-387, 1981. [3]. M. Scardamalia, C. Bereiter and H. Goleman, “The role of production factors in writing ability,” in What writers know: The language, process, and structure of written discourse, M. Nystrand, Ed. New York: Academic, 1982, pp. 173-210. [4]. G. Hull and M. Rose, “Rethinking remediation: Toward a social-cognitive understanding of problematic reading and writing,” Written Communication, vol. 6, pp. 139-154, 1989. [5]. B. K. Hofer, S. L. Yu and P. R. Pintrich, “Teaching college students to be self-regulated learners,” in Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice, D. H. Schunk and B. J. Zimmerman, Eds. New York: Guilford Press, 1998, pp. 57-85. [6]. F. Pajares and Y.F. Cheong, “Achievement goal orientations in writing: A developmental perspective,” International Journal of Educational Research, vol. 39, pp. 437-455, 2003. [7]. D. H. Schunk, “Social cognitive theory and self-regulated learning,” in Self-regulated learning and academic achievement theory, research, and practice progress in cognitive development research, B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk, Eds. New York: Springer- Verlag, 1989, pp. 83-110. [8]. B. Zimmerman, “Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn,” Contemporary Educational Psychology, vol. 25, pp. 82-91, 2000. Tran Quoc Thao et al. TNU Journal of Science and Technology Email: jst@tnu.edu.vn 54 [9]. M. Prat-Sala and P. Redford, “Does self- efficacy matters? The relationship between self-efficacy in reading and in writing and undergraduate students’ performance in essay writing,” Educational Psychology, vol. 32, pp. 9-20, 2012. [10]. T. M. Duong and S. Seepho, “Implementing a portfolio-based learner autonomy development model in an EFL writing course,” Suranaree Journal of Social Science, vol. 11, no.1, pp. 29-46, 2017. [11]. F. Pajares, M. Johnson and E. Usher, “Sources of writing self-efficacy beliefs of elementary, middle, and high school students,” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 42, no.1, pp. 104-120, 2007. [12]. F. Pajares and Y. F. Cheong, “Achievement goal orientations in writing: A developmental perspective,” International Journal of Educational Research, vol. 39, pp. 437-455, 2003. [13]. D. H. Schunk, “Social cognitive theory and self-regulated learning,” in Self-remdateci - leamina and academic achievement: Theory, research and practice, B. J. Zimrnerrnan and D. H. Schunk, Eds. New York: SpringerVerlag, 1989, pp. 83- 110. [14]. B. Zimmerman, “Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn,” Contemporary Educational Psychology, vol. 25, pp. 82-91, 2000. [15]. B. Zimmerman and A. Bandura, “Impact of self-regulatory influences on writing course attainment,” American Education Research Journal, vol. 31, pp. 845-862, 1994. [16]. D. Schunk, “Self-efficacy and academic motivation,” Educational Psychologist, vol. 26, pp. 207-231, 1991. [17]. A. Bandura, “Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning,” 225(11): 47 - 54 Educational Psychologist, vol. 28, no.2, pp. 117-148, 1993. [18]. P. R. Pintrich and E. V. DeGroot, “Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance,” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 82, pp. 33-40, 1990. [19]. B. J. Zimmerman, “Self-efficacy and educational development,” in Self-efficacy in changing societies, A. Bandura, Ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990, pp.202-231. [20]. A. Bandura, “Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies,” in Self-efficacy in changing societies, A. Bandura, Ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp.1-45. [21]. K. C. Hong, C. Wang, M. Bong, and S. A. Hyun, “Examining measurement properties of an English Self-Efficacy scale for English language learners in Korea,” International Journal of Educational Research, vol. 59, pp. 24–34, 2013. [22]. C. Wang, J. Hu, G. Zhang, Y. Chang and Y. Xu, “Chinese college students' self-regulated learning strategies and self-efficacy beliefs in learning English as a foreign language,” Journal of Research in Education, vol. 22, no.2, pp. 103–135, 2012. [23]. N. T. T. Phan and T. Locke, “Sources of self- efficacy of Vietnamese EFL teachers: A qualitative study,” Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 52, pp. 73-82, 2015. [24]. T. N. N. Truong and C. Wang, “Understanding Vietnamese college students’ self-efficacy beliefs in learning English as a foreign language,” System, vol. 84, pp. 123- 132, 2019.

File đính kèm:

tim_hieu_niem_tin_vao_nang_luc_viet_cua_sinh_vien_chuyen_nga.pdf

tim_hieu_niem_tin_vao_nang_luc_viet_cua_sinh_vien_chuyen_nga.pdf