Sự di cư của từ lóng tiếng Anh

Sự phát triển của tiếng lóng, đặc biệt là trong thời đại công nghệ thông tin hiện nay, đang có một

sức lan tỏa vô cùng mạnh mẽ, vượt qua rào cản ngôn ngữ và văn hóa giữa các quốc gia, trở thành một hiện

tượng và phong cách ngôn từ trong giới trẻ. Tiếng Việt cũng không nằm ngoài độ phủ sóng của hiện tượng

“di cư” ngôn ngữ đặc biệt này. Bài viết đề cập đến lịch sử phát triển của tiếng lóng Anh ngữ qua thời gian,

phân tích tâm lý giới trẻ và công nghệ thông tin như là chất xúc tác cho sự nhân rộng đó về mặt địa lý, đồng

thời nêu lên sự ảnh hưởng của tiếng lóng “di cư” đối với tiếng Việt, từ đó khẳng định nhu cầu nghiên cứu

thiết yếu về hiện tượng ngôn ngữ này.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Bạn đang xem tài liệu "Sự di cư của từ lóng tiếng Anh", để tải tài liệu gốc về máy hãy click vào nút Download ở trên

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Sự di cư của từ lóng tiếng Anh

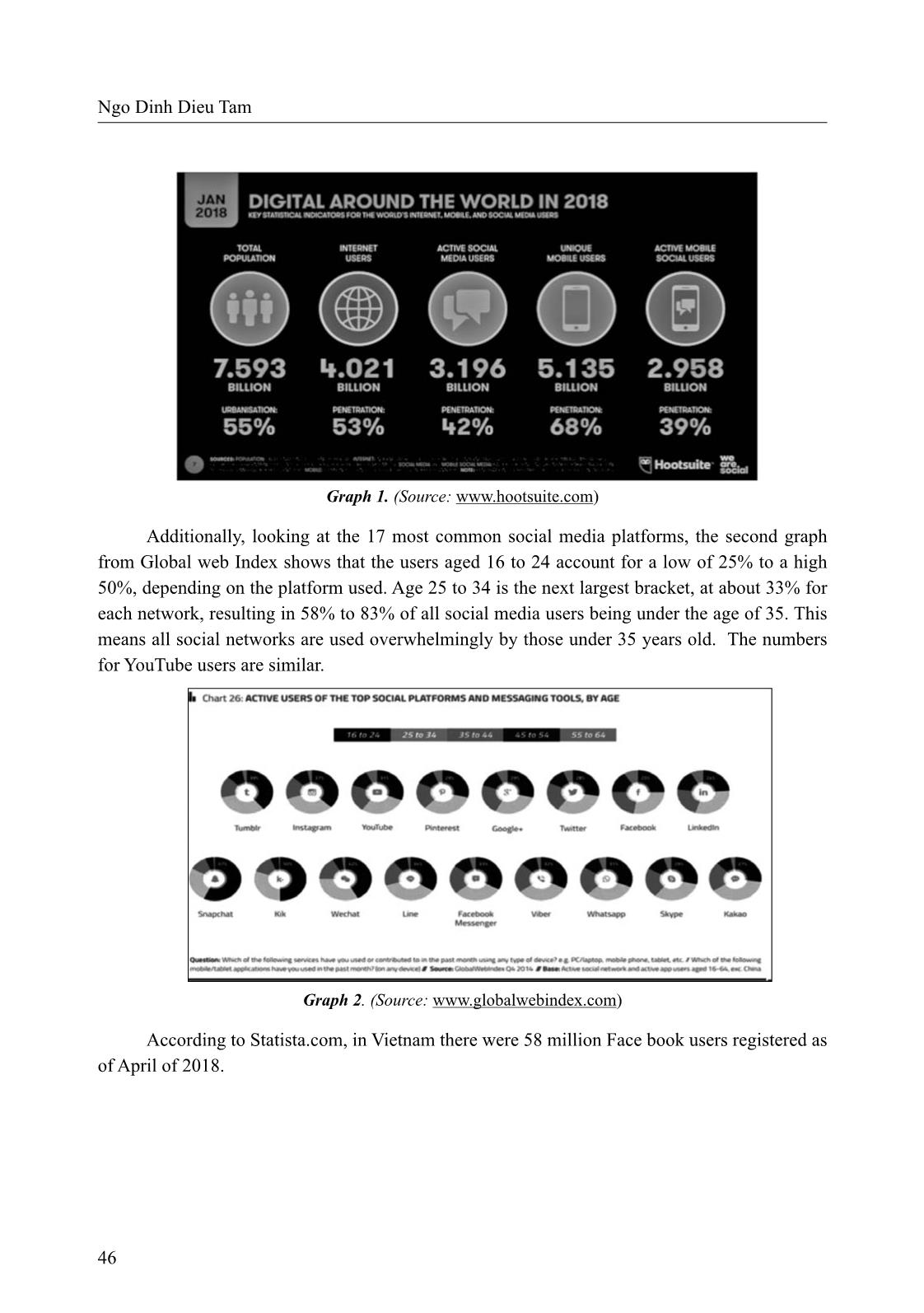

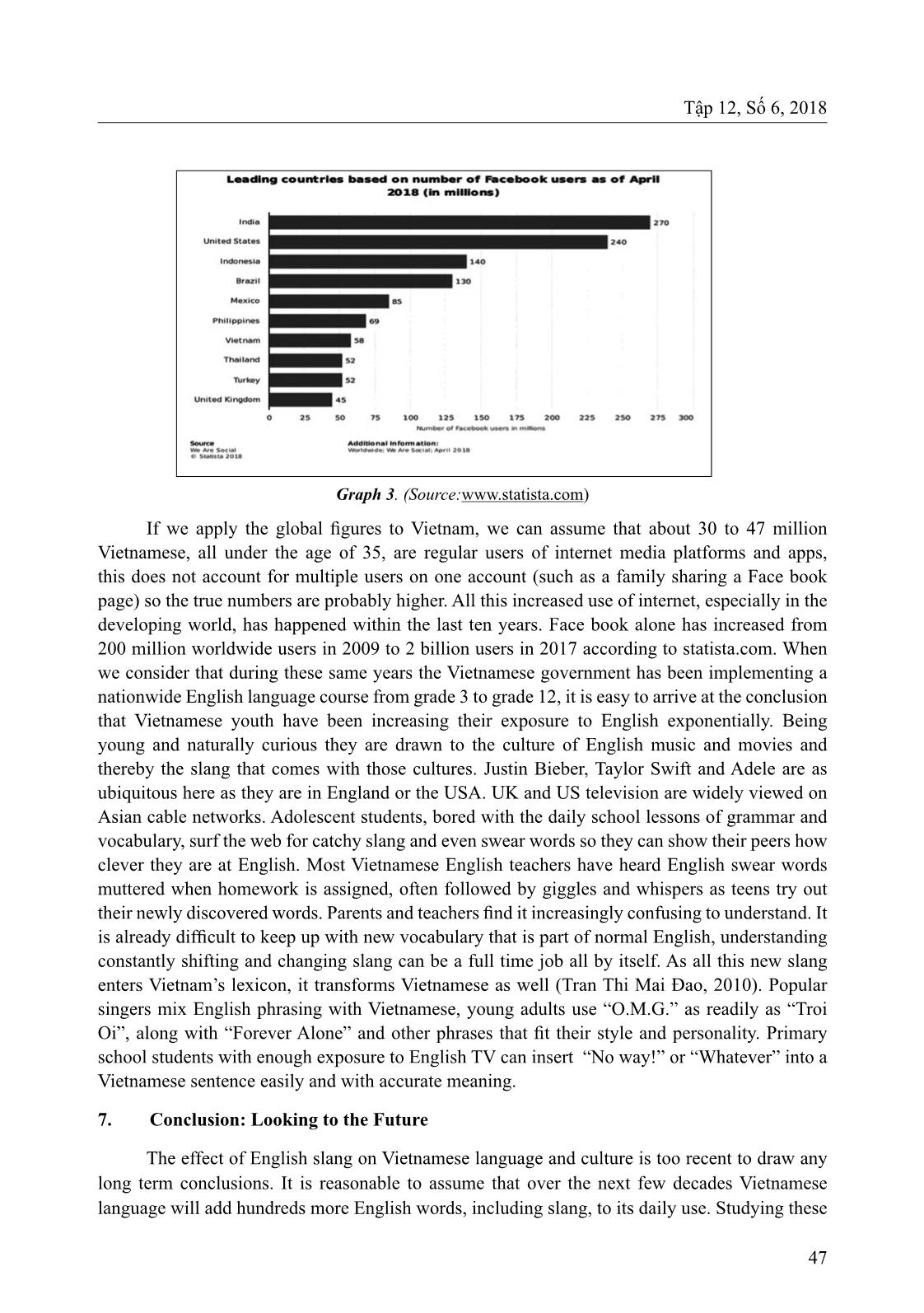

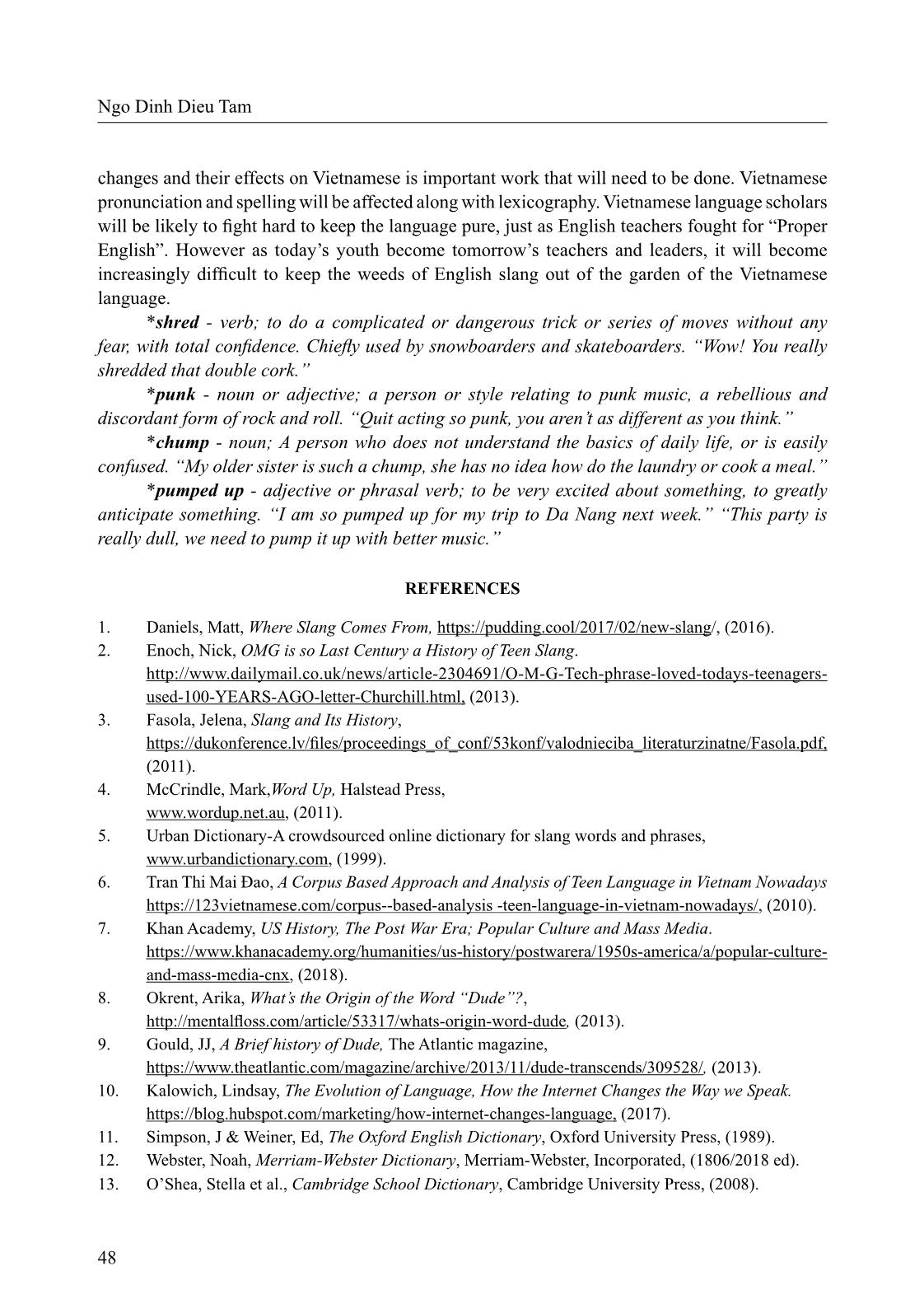

internet. 4. The Creation of New Slang The creation of new slang is always a part of any living language. English is possibly more susceptible to slang due to its global use and the immigrant populations in the UK and the USA. Not only do different nations and cultures add their own slang to English, the widespread teaching of English has made it nearly impossible to maintain a pure standardized version. With each succeeding generation, new words and meanings come into use. Some last for hundreds of years while others die out quickly. Every generation, usually while in their teen years, creates new ways to express themselves. Their goal is apparently to separate themselves from previous generations (ie: their parents) and create lexicography that is unique to their age, social group or groups they wish to be associated with. Creating their new “teen-speak” is often accomplished by altering the meaning and/or spelling of existing words or previous slang, or by creating entirely new words. Social groups that are farther from mainstream society, but intriguing to youth through music and media, tend to create more slang and also more unique slang. Consequently, groups such as musicians, surfers and inner city African Americans have contributed large amounts to teen slang throughout recent generations. 44 While much of slang is created anew with successive generations, some words survive many generations. These words may change in meaning and pronunciation, even spelling, however, a clear path can be traced as the word moves through the years. An excellent example of this is “cool”. The fi rst usage is over 100 years ago, originating in the Afro-American jazz culture of the early 20th century. Its meaning of “having soul or deep feeling” has evolved as it crossed social groups from Jazz musicians to beatniks (white hipsters of the 1950s) to the hippies in the 1960s, and then to California suburban Valley Girls in the 1990s. These girls used “kewl” to mean “in style” or “up to standard”. The meaning of cool has varied at times to mean excellent, ie: “That is a cool song, I love it.” to one of us as in this use: A: “I don’t trust John.” B: “Don’t worry, he’s cool.” It is still in use today and can carry, depending on context, most of its older meanings along with the most recent. It has been adopted by the advertising industry to market a variety of things from snack chips to bicycles. In fact it could be said that cool is no longer actual slang since it has been used by multiple generations, social groups and nationalities. English students from all continents use it easily and accurately. It has entered English permanently, carrying the positive meaning of being in current style, attractive or desirable. We might say that cool, as slang, is no longer cool, yet it persists. Aging baby boomers use it in the way they learned 40 to 50 years ago, while Generation Y has reversed its meaning, to be cool, according to them, is negative or anti- cool. (McCrindle, 2011) Another word that has been moving through a variety of uses for more than 150 years is “dude”. It fi rst appeared in the 1850s in New York to describe a well dressed, or perhaps fancily dressed male. Its exact beginnings are not known, however it might have crossed over from the German word “dude” for fool. Other research indicates it was shortened from “Yankee Doodle”, a phrase referring to foppish men of the day. It migrated west to the frontier areas of America and took on the meaning of any city man that wasn’t dressed or experienced in the rough ways of the cowboys, miners and other characters of those times. Synonyms include “city slicker” and “dandy”, all were derogatory and exclusionary in use. (Okrent, 2013). In the 1960s “dude” made a comeback among California surfers and skateboarders. It could be used to address any male and had the meaning of one who never gets upset, is always calm and laid back, also a good friend or mate. As in “Hey dude, let’s go get something to eat.” (Gould, 2013) In this use it is complimentary and inclusive. This new use expanded into mainstream culture and is now used all over the world, it has jumped gender lines and is used by young women as well, adding feminine suffi xes to create “dudine” and “dudette”. Examples of entirely new words that have entered teen vernacular are many, here are a few notable examples; “hangry” to be so hungry that you become angry and impatient, “crunk” drunk and acting crazy, “phat” meaning awesome or cool, and if a young man uses it to describe a young woman it means attractive. This last one is thought to have originated as an acronym for Pretty Hot And Tempting (Daniels, 2016). Interestingly, youth slang is predominantly tied to risky or immature activities such as drinking, parties, dating and sex. It rarely includes references to school or homework and the mundane parts of teen life. This may be because the original use of slang is thought to be a language created in the criminal parts of society and thus it allowed thieves and other lowlifes to Ngo Dinh Dieu Tam 45 Tập 12, Số 6, 2018 speak freely about their business without being understood by those around them, (Fasola, 2013). Much of today’s gangsta rap music slang has this same origin. Similarly, today’s teens often want to discuss their lives and not have their parents or teachers know exactly what is being said. Forinstance the phrase P.O.S. when spoken or typed means Parent Over Shoulder. One teen can tell friend on the phone or via message that a parent is watching or listening, without the parent knowing what has been said, ie: “My situation is POS right now.” Another technique to confuse adults is to give words opposite meaning. The word “sick” currently means awesome or great. If a parent overhears their teenager refer to a party with too much beer and loud music as “really sick” they would be inclined to think their child doesn’t like that sort of party, when in fact their teen is saying it sounds great. In the same way slang can be used to defi ne sub-groups within peer groups. Young people that are particularly interested in a certain music or activity may invent their own style of pronunciation or slant the meaning of existing slang so that it becomes recognizable only to members of that sub-group. This can create the feeling of membership in a clique that many teens desire, while excluding those that are not welcome. People that attempt to use slang from a group that they are not a part of are referred to as “wiggers”. From the notion of wearing a wig to change one’s appearance, or in this case trying to change your way of speaking to appear to be part of a group. An often humorous result of “wigging” is when wealthy non-African teens try to speak Ebonics, the slang and colloquial language of poor African-Americans which has been made widely available through popular music. 5. The Spread of Slang Today Now that smart phones and computers give us instant and constant connection to the web, young people have unfettered access to social networks and media sharing platforms such as Face book and YouTube. In addition to spreading slang at a rapid pace around the world, these devices and platforms also create the need for many new words to describe our use of them. Take the word “blog” for example, it is defi ned as a website that follows someone’s opinion or progress on some task or idea. It began as “web log”, using the defi nition of log to mean a diary or record of events, as in a ship’s log. The phrase web-log proved diffi cult to enunciate clearly and thus “blog” was born. Likewise phrases like cyber bullying and selfi e became necessary to describe actions that we were doing with our computers and phone cameras. However, the internet by itself doesn’t cause the creation of slang, it merely creates the need for new language to go with the new technology (Kalowich, 2017). The real signifi cance of the internet is the speed and totality of its infl uence. Youth in any country can now adopt “dude” and “selfi e” into their jargon at the same pace as their peers around the globe. 6. English Slang in Vietnam According to hootsuite.com (a global internet marketing research company) over 3 billion people worldwide used some form of social media in 2018, and more than 5 billion have mobile phones. That is 42% and 68% of world population respectively. (See graph number one.) 46 Graph 1. (Source: www.hootsuite.com) Additionally, looking at the 17 most common social media platforms, the second graph from Global web Index shows that the users aged 16 to 24 account for a low of 25% to a high 50%, depending on the platform used. Age 25 to 34 is the next largest bracket, at about 33% for each network, resulting in 58% to 83% of all social media users being under the age of 35. This means all social networks are used overwhelmingly by those under 35 years old. The numbers for YouTube users are similar. Graph 2. (Source: www.globalwebindex.com) According to Statista.com, in Vietnam there were 58 million Face book users registered as of April of 2018. Ngo Dinh Dieu Tam 47 Tập 12, Số 6, 2018 Graph 3. (Source:www.statista.com) If we apply the global fi gures to Vietnam, we can assume that about 30 to 47 million Vietnamese, all under the age of 35, are regular users of internet media platforms and apps, this does not account for multiple users on one account (such as a family sharing a Face book page) so the true numbers are probably higher. All this increased use of internet, especially in the developing world, has happened within the last ten years. Face book alone has increased from 200 million worldwide users in 2009 to 2 billion users in 2017 according to statista.com. When we consider that during these same years the Vietnamese government has been implementing a nationwide English language course from grade 3 to grade 12, it is easy to arrive at the conclusion that Vietnamese youth have been increasing their exposure to English exponentially. Being young and naturally curious they are drawn to the culture of English music and movies and thereby the slang that comes with those cultures. Justin Bieber, Taylor Swift and Adele are as ubiquitous here as they are in England or the USA. UK and US television are widely viewed on Asian cable networks. Adolescent students, bored with the daily school lessons of grammar and vocabulary, surf the web for catchy slang and even swear words so they can show their peers how clever they are at English. Most Vietnamese English teachers have heard English swear words muttered when homework is assigned, often followed by giggles and whispers as teens try out their newly discovered words. Parents and teachers fi nd it increasingly confusing to understand. It is already diffi cult to keep up with new vocabulary that is part of normal English, understanding constantly shifting and changing slang can be a full time job all by itself. As all this new slang enters Vietnam’s lexicon, it transforms Vietnamese as well (Tran Thi Mai Đao, 2010). Popular singers mix English phrasing with Vietnamese, young adults use “O.M.G.” as readily as “Troi Oi”, along with “Forever Alone” and other phrases that fi t their style and personality. Primary school students with enough exposure to English TV can insert “No way!” or “Whatever” into a Vietnamese sentence easily and with accurate meaning. 7. Conclusion: Looking to the Future The effect of English slang on Vietnamese language and culture is too recent to draw any long term conclusions. It is reasonable to assume that over the next few decades Vietnamese language will add hundreds more English words, including slang, to its daily use. Studying these 48 changes and their effects on Vietnamese is important work that will need to be done. Vietnamese pronunciation and spelling will be affected along with lexicography. Vietnamese language scholars will be likely to fi ght hard to keep the language pure, just as English teachers fought for “Proper English”. However as today’s youth become tomorrow’s teachers and leaders, it will become increasingly diffi cult to keep the weeds of English slang out of the garden of the Vietnamese language. *shred - verb; to do a complicated or dangerous trick or series of moves without any fear, with total confi dence. Chiefl y used by snowboarders and skateboarders. “Wow! You really shredded that double cork.” *punk - noun or adjective; a person or style relating to punk music, a rebellious and discordant form of rock and roll. “Quit acting so punk, you aren’t as different as you think.” *chump - noun; A person who does not understand the basics of daily life, or is easily confused. “My older sister is such a chump, she has no idea how do the laundry or cook a meal.” *pumped up - adjective or phrasal verb; to be very excited about something, to greatly anticipate something. “I am so pumped up for my trip to Da Nang next week.” “This party is really dull, we need to pump it up with better music.” REFERENCES 1. Daniels, Matt, Where Slang Comes From, https://pudding.cool/2017/02/new-slang/, (2016). 2. Enoch, Nick, OMG is so Last Century a History of Teen Slang. used-100-YEARS-AGO-letter-Churchill.html, (2013). 3. Fasola, Jelena, Slang and Its History, https://dukonference.lv/fi les/proceedings_of_conf/53konf/valodnieciba_literaturzinatne/Fasola.pdf, (2011). 4. McCrindle, Mark,Word Up, Halstead Press, www.wordup.net.au, (2011). 5. Urban Dictionary-A crowdsourced online dictionary for slang words and phrases, www.urbandictionary.com, (1999). 6. Tran Thi Mai Đao, A Corpus Based Approach and Analysis of Teen Language in Vietnam Nowadays https://123vietnamese.com/corpus--based-analysis -teen-language-in-vietnam-nowadays/, (2010). 7. Khan Academy, US History, The Post War Era; Popular Culture and Mass Media. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/postwarera/1950s-america/a/popular-culture- and-mass-media-cnx, (2018). 8. Okrent, Arika, What’s the Origin of the Word “Dude”?, oss.com/article/53317/whats-origin-word-dude, (2013). 9. Gould, JJ, A Brief history of Dude, The Atlantic magazine, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/11/dude-transcends/309528/, (2013). 10. Kalowich, Lindsay, The Evolution of Language, How the Internet Changes the Way we Speak. https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/how-internet-changes-language, (2017). 11. Simpson, J & Weiner, Ed, The Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, (1989). 12. Webster, Noah, Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, (1806/2018 ed). 13. O’Shea, Stella et al., Cambridge School Dictionary, Cambridge University Press, (2008). Ngo Dinh Dieu Tam

File đính kèm:

su_di_cu_cua_tu_long_tieng_anh.pdf

su_di_cu_cua_tu_long_tieng_anh.pdf