Phân tích cú pháp truyện ngắn tiếng Anh dành cho trẻ em

Với sự phát triển ngày càng gia tăng của kỹ thuật và phổ biến các nguồn tài liệu trên mạng, tài liệu

giáo dục nói chung và dạy học tiếng Anh như một ngoại ngữ nói riêng, bài viết này nhằm đóng góp vào nỗ

lực chung đó, với sự quan tâm với đối tượng thiếu nhi. Công trình này phân tích những đặc trưng cú pháp

của các truyện ngắn tiếng Anh dành cho thiếu nhi. Chúng tôi sử dụng phương pháp nghiên cứu phối hợp

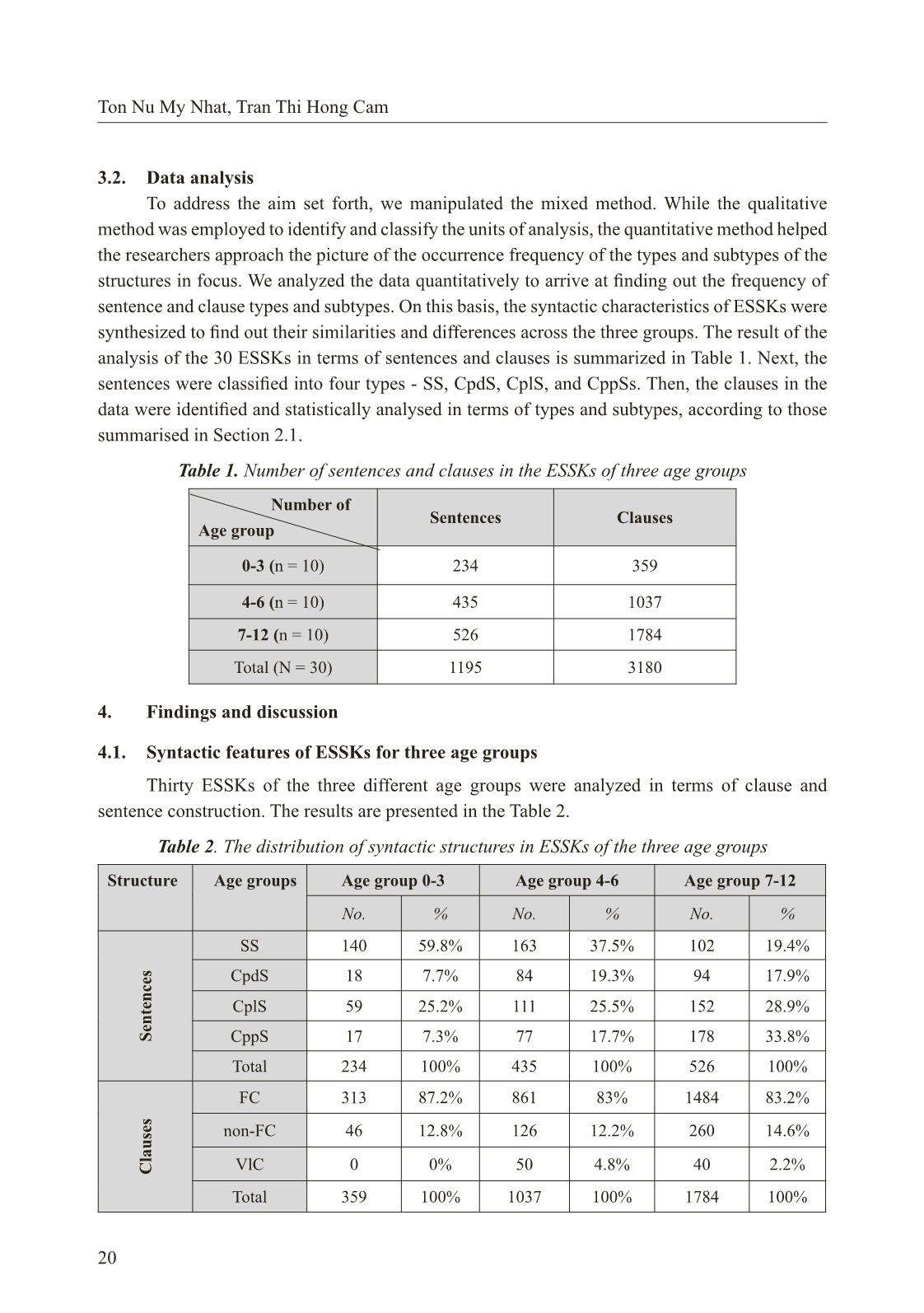

để nắm bắt bức tranh về cấu trúc cú pháp của câu và mệnh đề của truyện ngắn dành cho 3 nhóm - 0 - 3

tuổi, 4 - 6 tuổi, và 7 - 12 tuổi. Dữ liệu khảo sát là 30 truyện, 10 truyện cho mỗi nhóm, từ trang web . Kết quả khảo sát cho thấy tất cả các loại cấu trúc câu và mệnh đề, ngoại trừ loại mệnh

đề vắng động từ, đều được sử dụng trong cả 3 nhóm. Tuy nhiên, có sự khác nhau về tần số xuất hiện của mỗi loại cấu trúc ở các nhóm tuổi khác nhau; tần số sử dụng của các câu và mệnh đề phức tạp về cấu trúc lớn hơn khi đối tượng được hướng đến lớn tuổi hơn. Công trình phân tích cho thấy giá trị sư phạm của nguồn tư liệu này, chúng cần được sử dụng để phát triển năng lực tiếng Anh của thiếu nhi, đặc biệt ở những môi trường với điều kiện còn hạn chế.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Phân tích cú pháp truyện ngắn tiếng Anh dành cho trẻ em

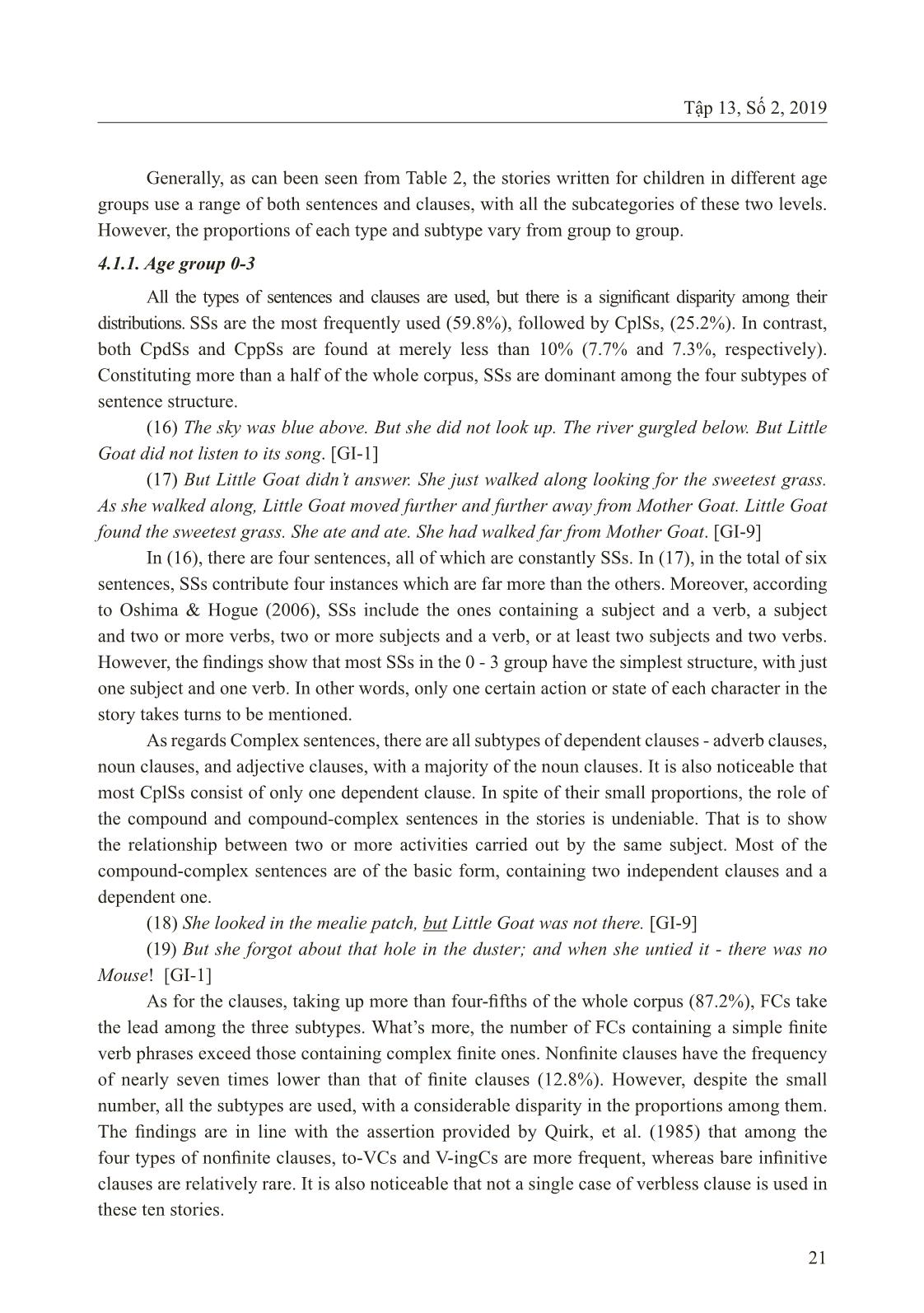

ed to investigate whether or not the online ESSKs are suitable for the different age groups they are targeted at, in terms of syntactic structures. From the in-depth description of the findings in the above section, we can now look at the underlying significance of the similarities and differences. There is no doubt that children aged 0 - 3 are at the first stage of language formation; hence, the writers of ESSKs in this group have a tendency to employ mostly short, simple sentences to get the very young readers start on their road to reading and grasping the moral lessons of the stories easily and quickly. In addition, it is worth noting that most of the SSs in this group are the ones containing a subject and a verb. The predominance of such simple structures emphasizes single actions of the characters, facilitating the young readers’ understanding and memorizing the contents. It is likely out of the same pedagogical reasons that the story writers utilize fewer complicated sentence structures, namely compound, complex, and compound-complex structures in the ESSKs for 0 - 3 age group. At the clause level, the finite clauses take the top priority, conveying explicitly the states and actions in terms of tense and aspect. The non-finite structures are much less frequent, just contributing to clarify extra details about the actions. Then, because verbless clauses take syntactic compression one stage further, which may present young readers with difficulties in inferring the missing information in those clauses, they are virtually absent. As for ESSKs for the age group 4 - 6, although SSs are the most frequent, its proportion decreases by 22.3% in comparison to those for the younger group. Then, though the proportion of finite clauses slightly decreases, it remains the most common clause type in ESSKs for this age group. It is also noticeable that verbless clauses begin to be used as well. This way, the children aged 4 - 6 both get access to the new clause structure and master the basic types. As regards the ESSKs of the age group 7 - 12, the percentage of SSs plunges, giving rise to the compound-complex and complex sentences, which are far much higher. This strategy of using sentence types in the group 7 - 12 seems to result from the intention that too many simple structures tend to make their stories appear childish, immature and boring to read. This high percentage of the complicated structures at the sentence level is coupled with a larger proportion of the nonfinite structures at the clause level. Furthermore, the writers of all three groups of ESSKs use a mixture of all sentence types in their own stories. This assists them in communicating and conveying the messages in those stories more flexibly and effectively. However, each sentence type is used with its own purposes of expressing; as a result, the distribution of each sentence type in the ESSKs of the three age groups is not the same. In fact, the simple sentences are recognized as the most popular types in all three groups. By using a large number of SSs, writers of ESSKs facilitate the young children in their first attempts to reading. Then, once the children grow older, it is likely that they may lose their interests in reading if they are faced with stories with mostly choppy simple sentences. Therefore, Ton Nu My Nhat, Tran Thi Hong Cam 25 Tập 13, Số 2, 2019 there is a preference for compound sentences to connect ideas of equal importance and relevance in ESSKs instead of just simple sentences for readers of 4 - 6 and 7 - 12. Besides, it is worth noting that the distributions of the complex sentences do not widely vary across three age groups. The justification for this may be that complex sentences play an essential part in smoothening the flow of information in stories, helping the readers focus on the main or subordinate ideas and contributing variety to the ESSKs. In the stories written for more grown-up readers, the occurrence frequency of the complex sentences increases stably, helping children be acquainted with this sentence structure step by step, without inhibiting their understanding. What’s more, the proportion of the compound-complex sentences the ESSKs for the oldest age group is nearly five times and twice as high as that in the group for the youngest and younger age groups, respectively. This suggests that the story writers carefully observe the readers’ cognition ability and language proficiency. Similarly, at the clause level, ESSKs also display a wide range of clause types, which enables the writers convey their ideas effectively while attentive to the age of the various groups. Finite clauses make up over four-fifths of the whole corpus, resulting from the fact that they may be used in both main and subordinate clauses. Besides, being the second most popular clause type used in ESSKs, nonfinite clauses add variety to the range of clause structure, thereby helping writers conveying meanings in their stories in a more economical way. In addition, it is worth discussing the fact that of all four subtypes of nonfinite clauses, the to-V clause and V-ing clause are the dominant, whereas the V-ed and the bare infinitive are quite rare. This finding is in line with the general tendency of use of these different structures of the clause, as observed by Quirk, et al. (1985). Finally, the smallest proportion of the verbless clauses in the whole data may be attributed to its minimum structure of either a noun phrase, an adjective phrase or an adverbial phrase, which may pose incomprehensibility to the young readers. The findings of this study, which concern short stories for young children, are to some extent contradict to those revealed from Wulandari’s (2015) study on sentence structures in the story About Barbers written by Mark Twain. The results of Wulandari’s analysis shows that compound sentence structure takes the lead in this short story, followed by compound-complex sentence structure, complex sentence structure and simple sentence structure in the order of the frequency percentages. The difference is highly likely due to the age of the readers targeted at. In Upreti’s (2012) study on the challenges and issues of making use of short stories as supplementary resources, he states that teachers face a lot of difficulty due to long structures and difficult vocabulary. On this basis, some suggestions which are put forward to reduce the challenges in teaching short stories such as trainings, workshops, refreshers courses are given regarding teaching short stories. Therefore, the results of the analysis uncover an encouraging fact that in terms of ‘syntactic complexity’, the stories under analysis, though selected by a native speaker of English for children around the world, are classified appropriately to be exploited in order of age and accordingly in order of grades of the YLs of EFL. Due to their prominent role, English stories have continually attracted extensive research. They have long been investigated from different perspectives, providing in-depth and comprehensive descriptions of this genre, such as in terms of semantic and syntactic features (Nguyen, 2012; Wulandari, 2015), of discourse markers (Altikriti, 2011; Youran, 26 Amoli & Youran, 2013), of conjunctions (Suswati, Sujatna, & Mahdi, 2014), or of meta-functions (Vu, 2014; Widayat, 2006). Concerning the practice of TEFL, studies have been conducted to explore the effectiveness of the using short stories in developing reading skill (Handayani, 2013; Pham, 2016), in immersing young children in moral values (Rahim & Rahiem, 2012), as well as to gauge the challenges and issues of making use of short stories as supplementary resources (Upreti, 2012). The present study is hoped to extend this fruitful area of research, contributing some practical insights into this ever-rich resource. 5. Conclusion This paper reports part of our endeavor to investigate the potential practicability of the online resources of English short stories to the benefits of YLs of EFL. The findings confirm the age-specific appropriateness of these quality free resources in terms of syntactic structures and thus point to the feasibility of immediate use, and preferably of further research of the inherent linguistic characteristics in tandems with the practice of exploiting them in various settings. The major limitation of this study lies with the small size of the data confined to only one website https://www.storyberries.com/. Besides, this research focuses on only the syntactic structure of the sentence and the clause. An investigation with a larger corpus comprising stories form other websites popular and most commonly accessed by children in a specific context in terms of the grammatical points and lexical loads covered in their formal English classes would have practical significance. Secondly, the websites which provide both the scripts and the voice may serve as another source of data to investigate the prosodic aspects for the same pedagogical purposes. Finally, a study into the teachers’, learners’, and parents’ attitude and practice, if any, and/or effectiveness of harnessing these online resources to the TEFL for YLs may also yield substantial benefits. REFERENCES 1. Abrams, M. H, A Glossary of Literary Terms (6th ed.), London: Harcourt Brace, (1993). 2. Altikriti, S. F., Speech act analysis to short stories, Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2 (6), 1374-1384, (2011). 3. Baldick, C., The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, Oxford: Oxford University Press, (2001). 4. Delahunty, G. P., & Garvey, J. J., The English Langauge from Sound to Sense, Indianna: Parlor Press, (2010). 5. Downing, A., & Locke, P. English Grammar: A University Course, New York: Routledge, (2006). 6. Jennings, C. Children as Story-tellers, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, (1991). 7. Matthews, B., The Philosophy of the Short-Story (C. May Ed. The New Short Story Theories ed.), Athens: Ohio University Press, (1994). 8. May, C., The Metaphoric Motivation in Short Fiction: In the Beginning Was the Story Short Story Theory at a Crossroads, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, (1989). 9. Nguyen, H. H., An Investigation into Semantic and Syntactic Features in the Vietnamese-English Translation of the Story “Vừa Nhắm Mắt Vừa Mở Cửa Sổ”, (Unpublished M.A Thesis), University of Danang, (2012). Ton Nu My Nhat, Tran Thi Hong Cam 27 Tập 13, Số 2, 2019 10. Oshima, A., & Hogue, A., Writing Academic English (4th ed.), New York: Pearson Longman, (2006). 11. Patea, V. Short Story Theories: A Twenty-first-century Perspective, New York: Rodopi, (2012). 12. Pham, A. L., A Study on Using Short Stories in Teaching Reading Skill at Nguyen Khuyen Secondary School, (Unpublished M.A Thesis), University of Languages and International Studies, (2016). 13. Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G., & Swartvik, J., A Comprehensive Grammar of The English Language, New York: Longman Inc, (1985). 14. Rahim, H., & Rahiem, M. D. H., The use of stories as moral education for young children, International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 2 (6), (2012). 15. Reddler, S., How Reading Stimulates Emotional Intelligence, Retrieved December 20, 2018 from https:///www.storyberries.com/how-reading-stimulates-emotional-intelligence, (2018). 16. Suswati, S., Sujatna, E. T. S., & Mahdi, S., Addictive conjunction choice in English children short stories: A syntactic and semantic analysis, International Journal of Language Learning and Applied Linguistics World, 5 (4), 11 - 21, (2014). 17. Upreti, K., Teaching Short Stories: Challenges And Issues, (Unpublished M.A Thesis), Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, (2012). 18. Vu, Q. T. N., A Discourse Analysis of Short Stories for Children in English and Vietnamese, (Unpublished M.A Thesis), Quy Nhon University, (2014). 19. Widayat, Y. E. W., A tenor analysis of short story entitled Cat in the Rain by Ernest Hemingway, (Unpublished Masters thesis), Sebelas Maret University Surakarta, (2006). 20. Wright, A., Stories and their importance in language teaching, Humanising Language Teaching, 2 (5), pp. 1 - 6. (2000). 21. Wulandari, D. P., Syntactic analysis of Mark Twain’s About Barbers on Leech’s Method, Rainbow: Journal of Literature, Linguistics and Cultural Studies, 4 (1), 37 - 43, (2015). 22. Youran, M., Amoli, F. A., & Youran, F., The study of markers in the narration of children’s short story. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 2 (3), 305 - 308, (2013). 23. Elliott, J. “Interesting ESL group activities”, Retrieved February 12, 2011 from ESLarticle.com /(2011). 24. Phillips, S., Young learners, OUP, (1993). 25. Scott, W. A. and Ytreberg, L. H., Teaching English to children, New York: Longman, (1993). 26. Slattery, M. and Willis, J., English for primary teachers - A handbook of activities and classroom language, OUP, (2001). 27. Website: https://www.storyberries.com/. APPENDIX: List of Samples in Data (GI: Age 0 - 3; GII: Age 4 - 6; GIII: Age 7 - 12) Code Title of story & Name of author GI-1 The Story of Miss Moppet (Beatrix Potter) GI-2 Londi the Dreaming Girl (Lauren Holliday & Nathalie Koenig) GI-3 The Happy Hat (Jade Matre) GI-4 The Best Thing Ever (Melissa Fagan) GI-5 What Is It? (Kate Sidley) GI-6 Hippo Wants to Dance (Sam Beckbessinger) 28 GI-7 Little Ant’s Big Plan (Candice Dingwall) GI-8 Jimmy the Cat and Bobik’s Birthday (Katty Melnichenko) GI-9 Little goat (Mirna Lawrence) GI-10 Whose Button Is This? (Paul Kennedy) GII-1 Monsieur-le-dot (Jade Matre) GII-2 The Princess and the Pea (Hans Christian Andersen) GII-3 Dolly Dimple (H.W. Mabie, E. E. Hale and W. B. Forbush) GII-4 The Mouse and the Sausage (H.W. Mabie, E.E.Hale and W. B. Forbush) GII-5 Fox and the Pine (Danielle Noakes) GII-6 The Tale of Two Bad Mice (Beatrix Potter) GII-7 The Tale of Mrs Tittlemouse (Beatrix Potter) GII-8 The Tale of Mr Jeremy Fisher (Beatrix Potter) GII-9 The Tale of Peter Rabbit (Beatrix Potter) GII-10 The Tale of Tom Kitten (Beatrix Potter) GIII-1 Rabbit’s Eyes (Katharine Pyle) GIII-2 The Faithless Parrot (Charles H. Bennett) GIII-3 The Musicians of Bremen (Brothers Grimm) GIII-4 The Little Match Girl (Hans Christian Andersen) GIII-5 The White Stone Canoe (H. W. Mabie, E. E. Hale and W. B.Forbush) GIII-6 In Search of a Baby (H.W. Mabie, E. E. Hale and W. B.Forbush) GIII-7 The Three Little Pigs (Joseph Jacobs) GIII-8 The Maiden Who Loved a Fish (H.W. Mabie, E. E.Hale and W.B. Forbush) GIII-9 Fundevogel (Brothers Grimm) GIII-10 Old Sultan (Brothers Grimm) Ton Nu My Nhat, Tran Thi Hong Cam

File đính kèm:

phan_tich_cu_phap_truyen_ngan_tieng_anh_danh_cho_tre_em.pdf

phan_tich_cu_phap_truyen_ngan_tieng_anh_danh_cho_tre_em.pdf