An improving way for Website security assessment

The web-based enterprise applications, such as e-commerce, online banking, online auction, social networks,

forums. . . , have been more and more popular in our society. These applications become the target of security attacks.

Hence, securing websites and connection to the users is important. If we own or manage a website, we certainly concern

about how secure it is. For assessing the security level of a website, we usually take some action, including testing the

website using security scanning tools. Unfortunately, most of scanning tools have limitations and need to be updated

frequently for new vulnerabilities. Using only one scanning tool is sometime not enough to determine security level of a

website. In this paper we propose a framework supporting website security assessment. The idea of this framework is to

integrate different scanning tools into the framework. We then write a program to implement this framework with a real

website. We guide the users how to add a new scanning tool to this framework, manage it and generate a final report. In

addition, we discuss the problem of security on client-side called clickjacking attack that many clients may suffer when

accessing the malicious websites, we propose a method to p

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: An improving way for Website security assessment

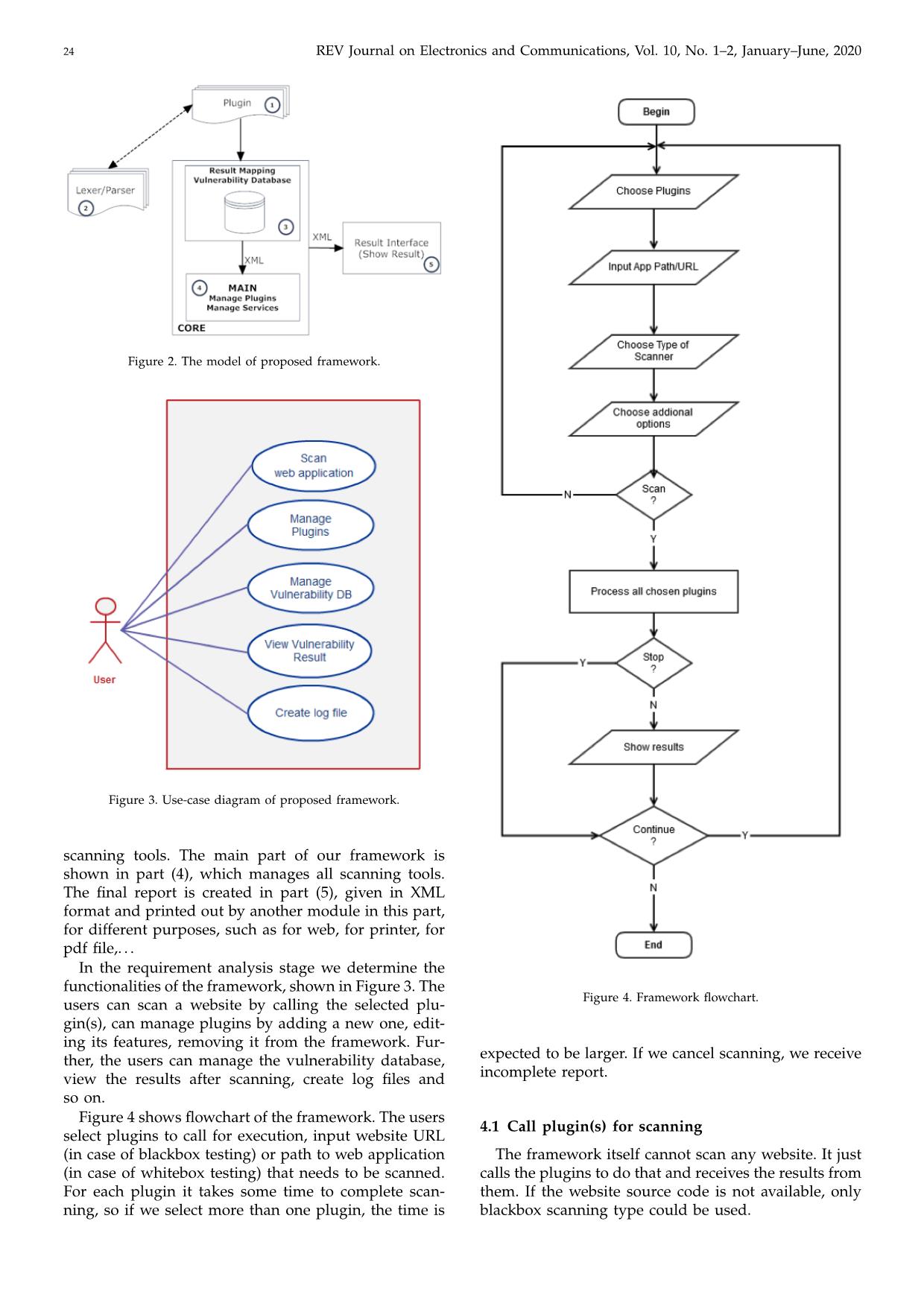

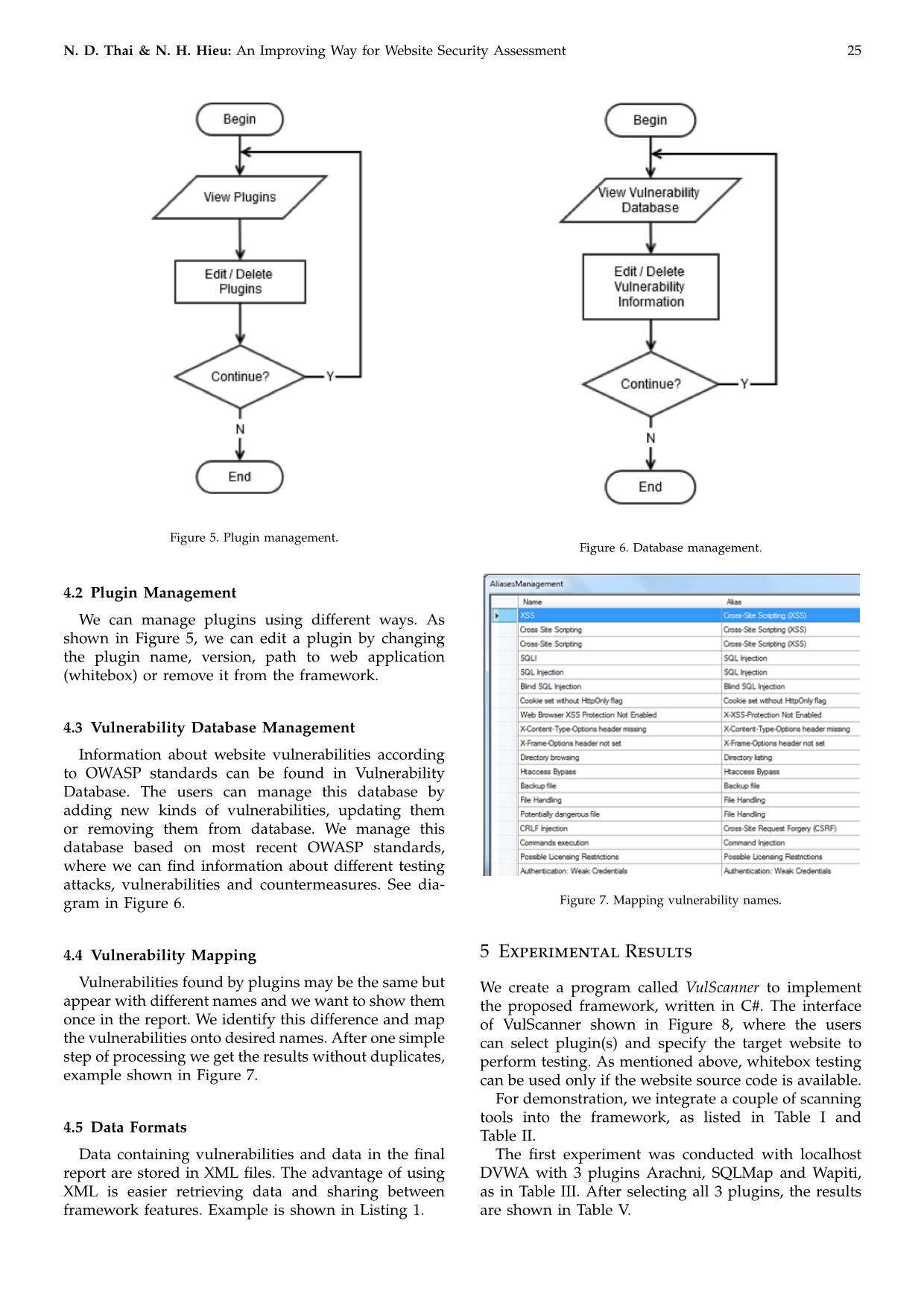

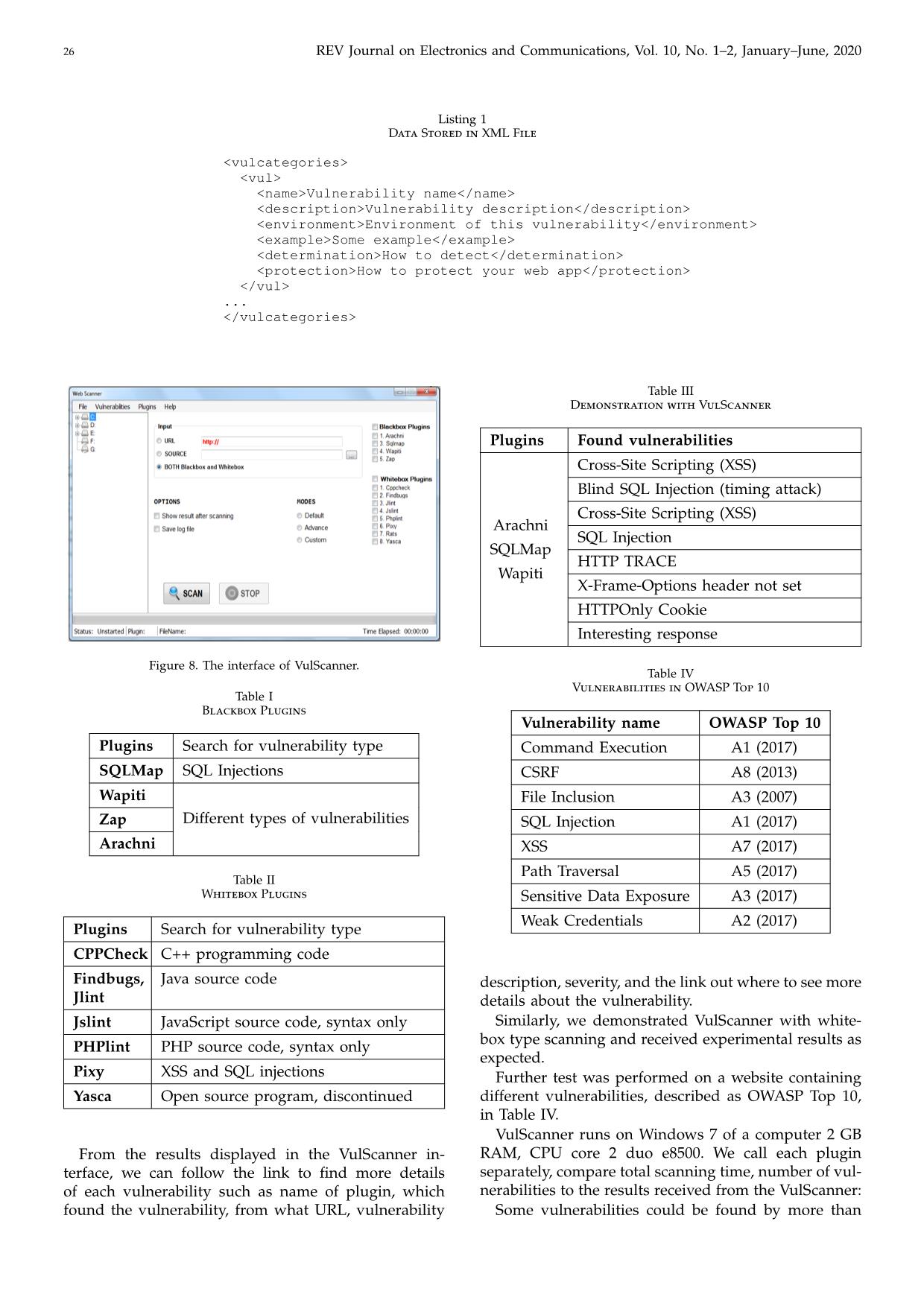

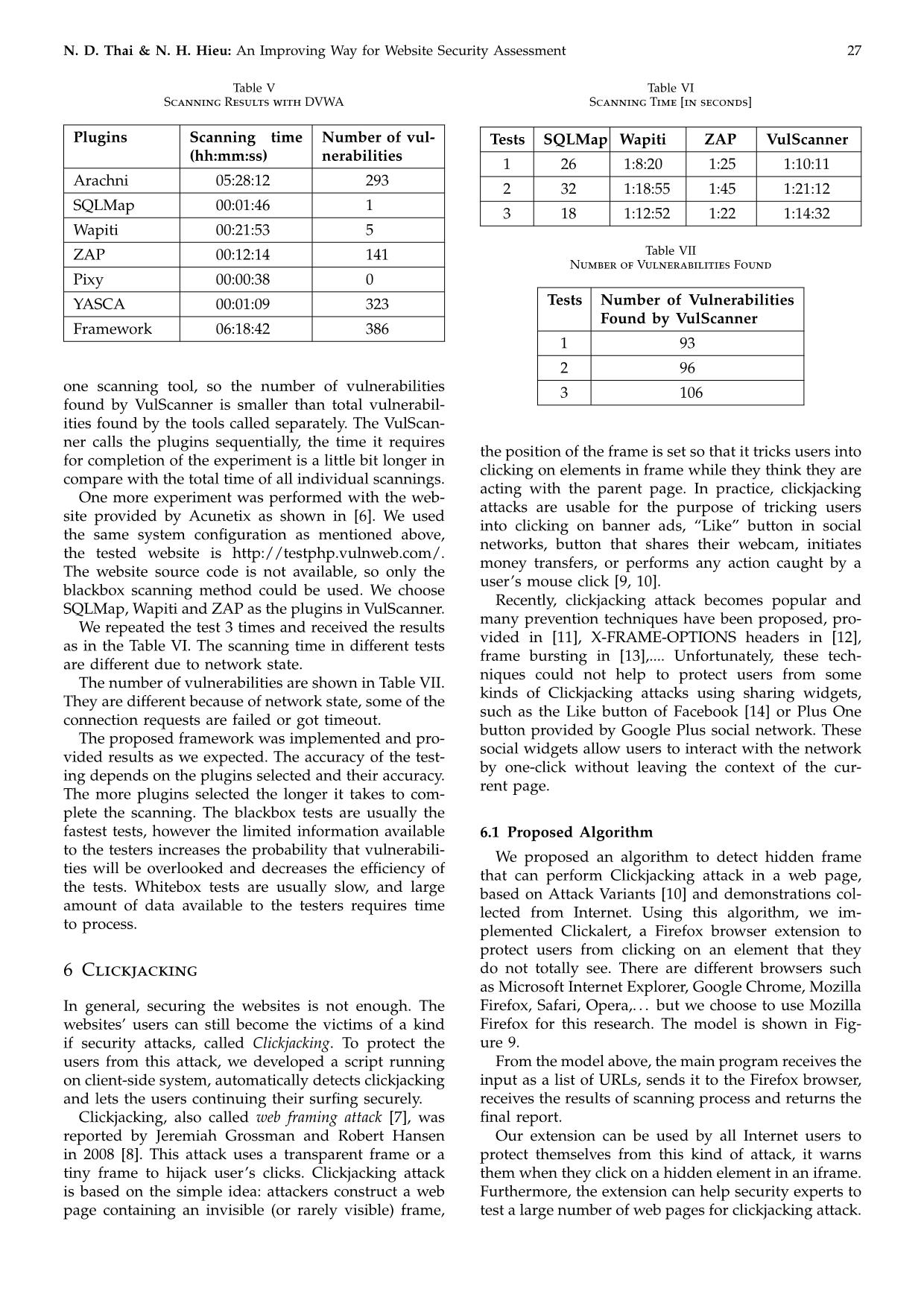

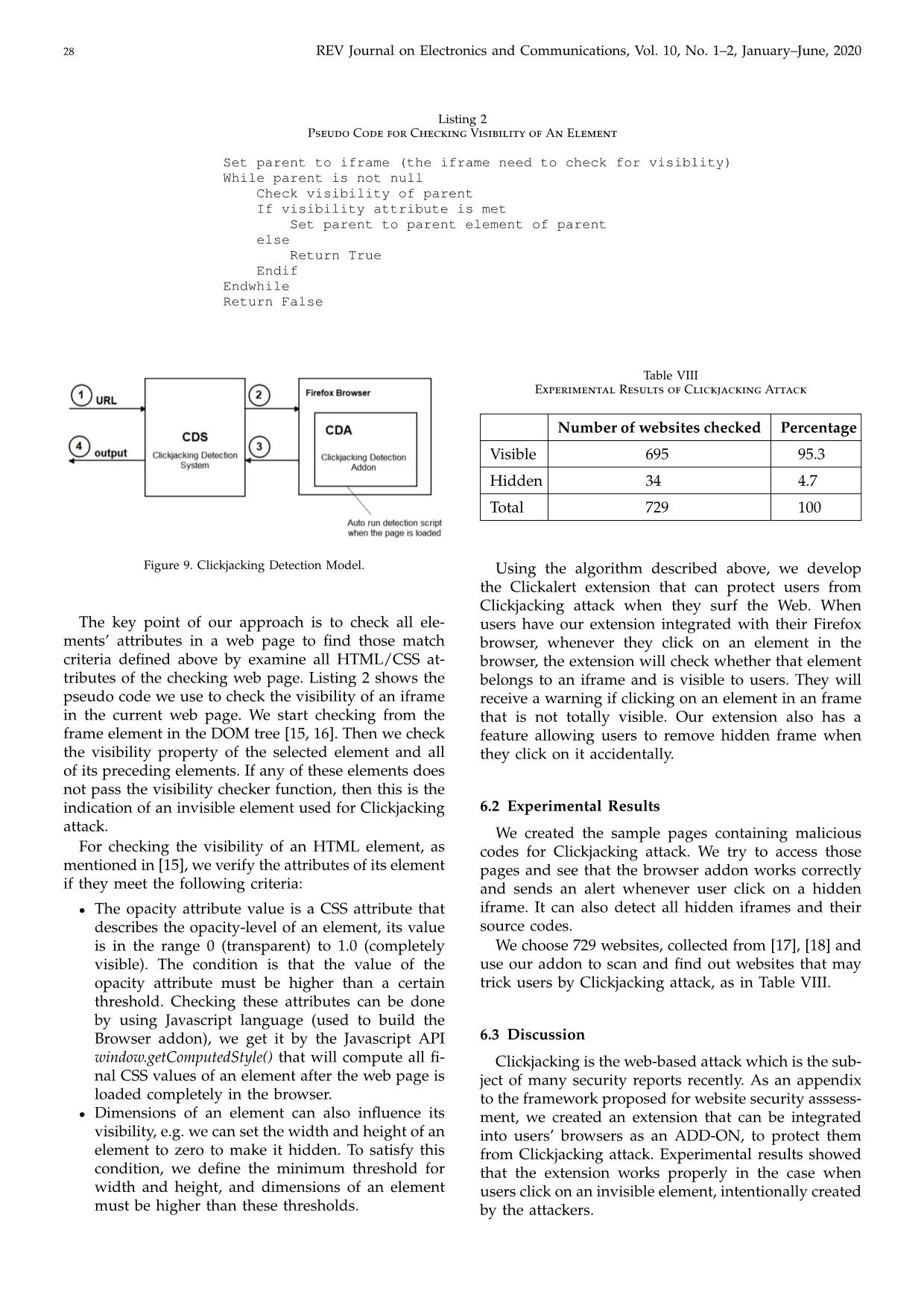

o protect your web app ... Figure 8. The interface of VulScanner. Table I Blackbox Plugins Plugins Search for vulnerability type SQLMap SQL Injections Wapiti Different types of vulnerabilitiesZap Arachni Table II Whitebox Plugins Plugins Search for vulnerability type CPPCheck C++ programming code Findbugs, Jlint Java source code Jslint JavaScript source code, syntax only PHPlint PHP source code, syntax only Pixy XSS and SQL injections Yasca Open source program, discontinued From the results displayed in the VulScanner in- terface, we can follow the link to find more details of each vulnerability such as name of plugin, which found the vulnerability, from what URL, vulnerability Table III Demonstration with VulScanner Plugins Found vulnerabilities Arachni SQLMap Wapiti Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Blind SQL Injection (timing attack) Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) SQL Injection HTTP TRACE X-Frame-Options header not set HTTPOnly Cookie Interesting response Table IV Vulnerabilities in OWASP Top 10 Vulnerability name OWASP Top 10 Command Execution A1 (2017) CSRF A8 (2013) File Inclusion A3 (2007) SQL Injection A1 (2017) XSS A7 (2017) Path Traversal A5 (2017) Sensitive Data Exposure A3 (2017) Weak Credentials A2 (2017) description, severity, and the link out where to see more details about the vulnerability. Similarly, we demonstrated VulScanner with white- box type scanning and received experimental results as expected. Further test was performed on a website containing different vulnerabilities, described as OWASP Top 10, in Table IV. VulScanner runs on Windows 7 of a computer 2 GB RAM, CPU core 2 duo e8500. We call each plugin separately, compare total scanning time, number of vul- nerabilities to the results received from the VulScanner: Some vulnerabilities could be found by more than N. D. Thai & N. H. Hieu: An Improving Way for Website Security Assessment 27 Table V Scanning Results with DVWA Plugins Scanning time (hh:mm:ss) Number of vul- nerabilities Arachni 05:28:12 293 SQLMap 00:01:46 1 Wapiti 00:21:53 5 ZAP 00:12:14 141 Pixy 00:00:38 0 YASCA 00:01:09 323 Framework 06:18:42 386 one scanning tool, so the number of vulnerabilities found by VulScanner is smaller than total vulnerabil- ities found by the tools called separately. The VulScan- ner calls the plugins sequentially, the time it requires for completion of the experiment is a little bit longer in compare with the total time of all individual scannings. One more experiment was performed with the web- site provided by Acunetix as shown in [6]. We used the same system configuration as mentioned above, the tested website is The website source code is not available, so only the blackbox scanning method could be used. We choose SQLMap, Wapiti and ZAP as the plugins in VulScanner. We repeated the test 3 times and received the results as in the Table VI. The scanning time in different tests are different due to network state. The number of vulnerabilities are shown in Table VII. They are different because of network state, some of the connection requests are failed or got timeout. The proposed framework was implemented and pro- vided results as we expected. The accuracy of the test- ing depends on the plugins selected and their accuracy. The more plugins selected the longer it takes to com- plete the scanning. The blackbox tests are usually the fastest tests, however the limited information available to the testers increases the probability that vulnerabili- ties will be overlooked and decreases the efficiency of the tests. Whitebox tests are usually slow, and large amount of data available to the testers requires time to process. 6 Clickjacking In general, securing the websites is not enough. The websites’ users can still become the victims of a kind if security attacks, called Clickjacking. To protect the users from this attack, we developed a script running on client-side system, automatically detects clickjacking and lets the users continuing their surfing securely. Clickjacking, also called web framing attack [7], was reported by Jeremiah Grossman and Robert Hansen in 2008 [8]. This attack uses a transparent frame or a tiny frame to hijack user’s clicks. Clickjacking attack is based on the simple idea: attackers construct a web page containing an invisible (or rarely visible) frame, Table VI Scanning Time [in seconds] Tests SQLMap Wapiti ZAP VulScanner 1 26 1:8:20 1:25 1:10:11 2 32 1:18:55 1:45 1:21:12 3 18 1:12:52 1:22 1:14:32 Table VII Number of Vulnerabilities Found Tests Number of Vulnerabilities Found by VulScanner 1 93 2 96 3 106 the position of the frame is set so that it tricks users into clicking on elements in frame while they think they are acting with the parent page. In practice, clickjacking attacks are usable for the purpose of tricking users into clicking on banner ads, “Like” button in social networks, button that shares their webcam, initiates money transfers, or performs any action caught by a user’s mouse click [9, 10]. Recently, clickjacking attack becomes popular and many prevention techniques have been proposed, pro- vided in [11], X-FRAME-OPTIONS headers in [12], frame bursting in [13],.... Unfortunately, these tech- niques could not help to protect users from some kinds of Clickjacking attacks using sharing widgets, such as the Like button of Facebook [14] or Plus One button provided by Google Plus social network. These social widgets allow users to interact with the network by one-click without leaving the context of the cur- rent page. 6.1 Proposed Algorithm We proposed an algorithm to detect hidden frame that can perform Clickjacking attack in a web page, based on Attack Variants [10] and demonstrations col- lected from Internet. Using this algorithm, we im- plemented Clickalert, a Firefox browser extension to protect users from clicking on an element that they do not totally see. There are different browsers such as Microsoft Internet Explorer, Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Safari, Opera,. . . but we choose to use Mozilla Firefox for this research. The model is shown in Fig- ure 9. From the model above, the main program receives the input as a list of URLs, sends it to the Firefox browser, receives the results of scanning process and returns the final report. Our extension can be used by all Internet users to protect themselves from this kind of attack, it warns them when they click on a hidden element in an iframe. Furthermore, the extension can help security experts to test a large number of web pages for clickjacking attack. 28 REV Journal on Electronics and Communications, Vol. 10, No. 1–2, January–June, 2020 Listing 2 Pseudo Code for Checking Visibility of An Element Set parent to iframe (the iframe need to check for visiblity) While parent is not null Check visibility of parent If visibility attribute is met Set parent to parent element of parent else Return True Endif Endwhile Return False Figure 9. Clickjacking Detection Model. The key point of our approach is to check all ele- ments’ attributes in a web page to find those match criteria defined above by examine all HTML/CSS at- tributes of the checking web page. Listing 2 shows the pseudo code we use to check the visibility of an iframe in the current web page. We start checking from the frame element in the DOM tree [15, 16]. Then we check the visibility property of the selected element and all of its preceding elements. If any of these elements does not pass the visibility checker function, then this is the indication of an invisible element used for Clickjacking attack. For checking the visibility of an HTML element, as mentioned in [15], we verify the attributes of its element if they meet the following criteria: • The opacity attribute value is a CSS attribute that describes the opacity-level of an element, its value is in the range 0 (transparent) to 1.0 (completely visible). The condition is that the value of the opacity attribute must be higher than a certain threshold. Checking these attributes can be done by using Javascript language (used to build the Browser addon), we get it by the Javascript API window.getComputedStyle() that will compute all fi- nal CSS values of an element after the web page is loaded completely in the browser. • Dimensions of an element can also influence its visibility, e.g. we can set the width and height of an element to zero to make it hidden. To satisfy this condition, we define the minimum threshold for width and height, and dimensions of an element must be higher than these thresholds. Table VIII Experimental Results of Clickjacking Attack Number of websites checked Percentage Visible 695 95.3 Hidden 34 4.7 Total 729 100 Using the algorithm described above, we develop the Clickalert extension that can protect users from Clickjacking attack when they surf the Web. When users have our extension integrated with their Firefox browser, whenever they click on an element in the browser, the extension will check whether that element belongs to an iframe and is visible to users. They will receive a warning if clicking on an element in an frame that is not totally visible. Our extension also has a feature allowing users to remove hidden frame when they click on it accidentally. 6.2 Experimental Results We created the sample pages containing malicious codes for Clickjacking attack. We try to access those pages and see that the browser addon works correctly and sends an alert whenever user click on a hidden iframe. It can also detect all hidden iframes and their source codes. We choose 729 websites, collected from [17], [18] and use our addon to scan and find out websites that may trick users by Clickjacking attack, as in Table VIII. 6.3 Discussion Clickjacking is the web-based attack which is the sub- ject of many security reports recently. As an appendix to the framework proposed for website security asssess- ment, we created an extension that can be integrated into users’ browsers as an ADD-ON, to protect them from Clickjacking attack. Experimental results showed that the extension works properly in the case when users click on an invisible element, intentionally created by the attackers. N. D. Thai & N. H. Hieu: An Improving Way for Website Security Assessment 29 7 Conclusions The contribution of our paper is not in creation of a new scanning tool, but we suggest the way to integrate different plugins to get better results. We showed that it is very easy to add a new plugin to the framework, easy to configure the framework to work with the new plugin. Different tools give results in different format, so we need to map them onto desired format as provided by OWASP. The results given by our framework can be acceptable, however we can speedup the scanning by running the tools in parallel, we consider this issue in the future work. Regard the clickjacking, we provided an effective way to detect hidden frames, then we implemented it in Firefox. This tool can protect users from clickjacking on an element that they do not see. Acknowledgment This research is funded by Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City, under grant number C2017-20-19. References [1] Symantec Internet Security Report, vol. 24, 2019. [2] OWASP Top 10 Most Critical Web Application Security Risks. [Online]. Available: https://www.owasp.org/ in- dex.php/Category:OWASP_Top_Ten_Project (accessed Jan. 25, 2019) [3] YASCA, official website. [Online]. Available: yasca.org, or on Github: https://github.com/scovetta/yasca (accessed Jul. 2018) [4] J. Bau, E. Bursztein, D. Gupta, and J. Mitchell, “State of the art: Automated black-box web application vulnera- bility testing,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. IEEE, 2010, pp. 332–345. [5] D. Esposito, M. Rennhard, L. Ruf, and A. Wagner, “Ex- ploiting the potential of web application vulnerability scanning,” in Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Internet Monitoring and Protection, 2018, pp. 22–29. [6] Home of Acunetix Art. [Online]. Available: http:// testphp.vulnweb.com (accessed Aug. 2019) [7] Cursorjacking again. [Online]. Available: kotowicz.net/2012/01/cursorjacking-again.html (accessed Jan. 2012) [8] R. Hansen and J. Grossman. Clickjacking. [Online]. Available: (accessed Jan. 25, 2019) [9] M. Johns and S. Lekies, “Tamper-resistant likejacking protection,” in Proceedings of the International Workshop on Recent Advances in Intrusion Detection. Springer, 2013, pp. 265–285. [10] L.-S. Huang, A. Moshchuk, H. J. Wang, S. Schecter, and C. Jackson, “Clickjacking: Attacks and defenses,” in Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Security Symposium, 2012, pp. 413–428. [11] A. S. Narayanan, “Clickjacking vulnerability and coun- termeasures,” International Journal of Applied Information Systems, vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 7–10, 2012. [12] D. Ross, T. Gondrom, and T. Stanley. HTTP Header Field X-Frame-Options (RFC 7034) (2013) InternetEngineering Task Force (IETF). [Online]. Avail- able: https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc7034.txt (accessed Jan. 2018) [13] G. Rydstedt, E. Bursztein, D. Boneh, and C. Jackson, “Busting frame busting:a study of clickjacking vulner- abilities on popular sites,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Oakland Web 2.0 Security and Privacy (W2SP’10). [14] Facebook worm - “likejacking”. [Online]. Available: facebook-likejacking-worm/ (accessed May 2010) [15] P. Thiemann, “A type safe DOM API,” in Proceedings of the International Workshop on Database Programming Languages. Springer, 2005, pp. 169–183. [16] M. Heiderich, T. Frosch, and T. Holz, “Iceshield: Detec- tion and mitigation of malicious websites with a frozen dom,” in International Workshop on Recent Advances in Intrusion Detection. Springer, 2011, pp. 281–300. [17] Top 1000 website. [Online]. Available: https://www. alexa.com/topsites [18] Free web stats counter from motigo webstats - catalogue/top 1000 sites. [Online]. Available: https:// trends.builtwith.com/websitelist/Motigo-Stats Nguyen Duc Thai received BSc. (MSc.) and Ph.D. from Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava, Slovakia, in 1996 and 2005 respec- tively. He is currently Head of Department of Computer Systems and Networking, Faculty of Computer Science and Engineering, Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology. He has been actively involved as a researcher and teacher in the area of computer networks and network security for many years. Nguyen Huu Hieu is currently a full time researcher at Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology. He received his B.Sc. and M.Sc. degree from Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology in 2012 and 2015, respectively. His current research interests include network security and website security.

File đính kèm:

an_improving_way_for_website_security_assessment.pdf

an_improving_way_for_website_security_assessment.pdf