Vietnamese tea exporting and forecasting to 2030

This study aimed to determine the factors influencing Vietnamese tea

export quantities, namely, the internal factors of national tea

production, productivity, and cultivated areas, and the external

factors of export price and world tea export quantity (excluding

Vietnam). We employed a time-series linear model to estimate the

magnitude as well as the sign of the aforementioned factors on

Vietnam’s tea export quantity and two Box-Cox transformations

called a simple back-transformed forecast and a bias-adjustment to

forecast the growth rate of the Vietnamese tea export quantity until

2030. The results suggested that except for the total domestic tea

production, all the proposed factors significantly affected the

Vietnamese tea export quantity. The tea export quantity of other

nations around the world had a significantly negative impact on

Vietnamese tea that led to Vietnam’s tea exports dropping by 34 tons

on average since the other countries exported 1,000 tons of tea. The

forecasted outcome suggested an upward trend of Vietnamese tea

exports up to 2030. In order to sustainably develop Vietnam’s tea

industry, we recommend that the government should take supportive

actions such as investing in in-depth tea processing to improve

Vietnam’s tea export quality, focusing on post-harvest activities,

investing in organic or high-value tea rather than conventional tea,

continuing to accumulate land to support the growth of cultivated

tea areas, and maintaining high productivity by using hybrid seeds.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Vietnamese tea exporting and forecasting to 2030

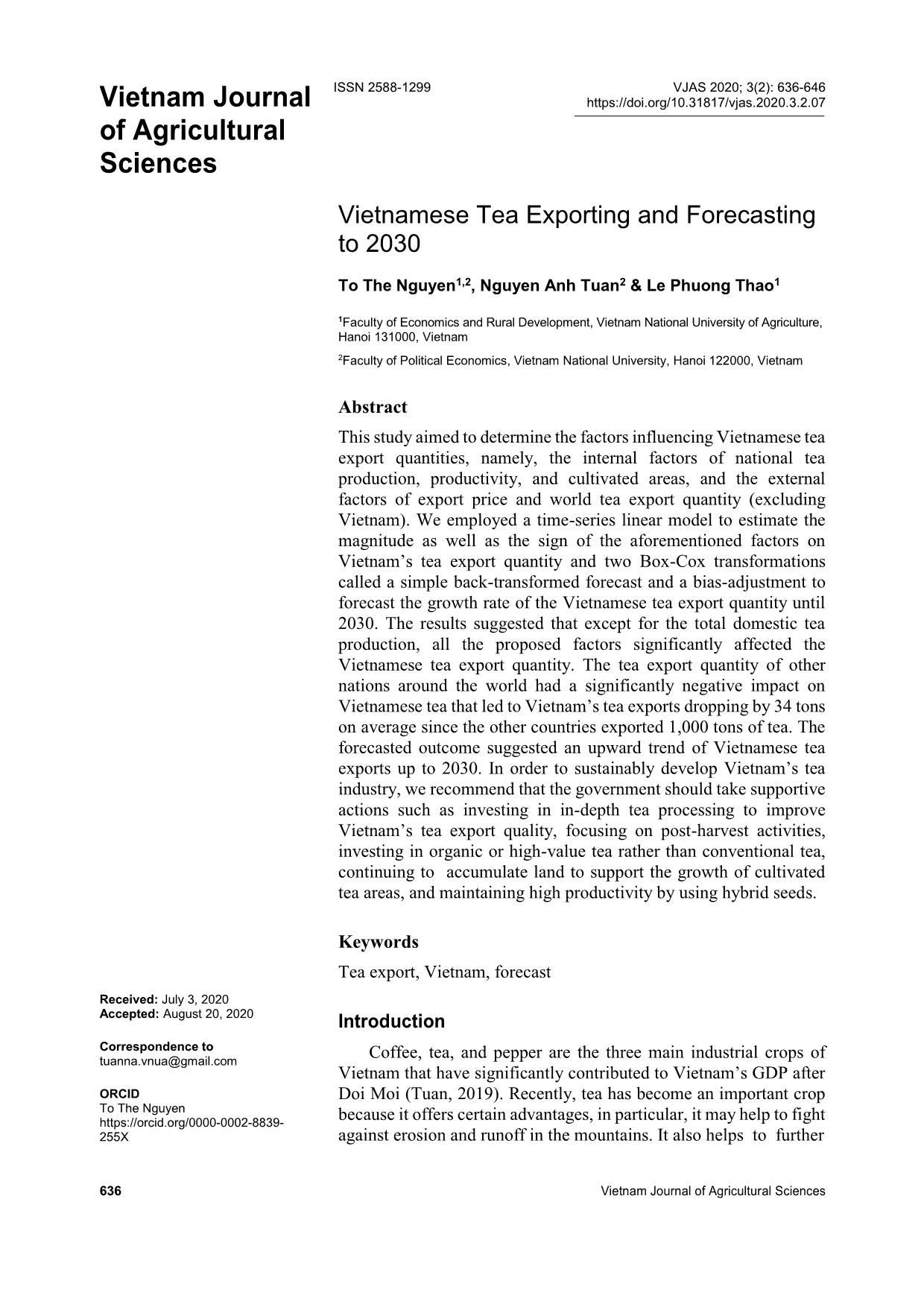

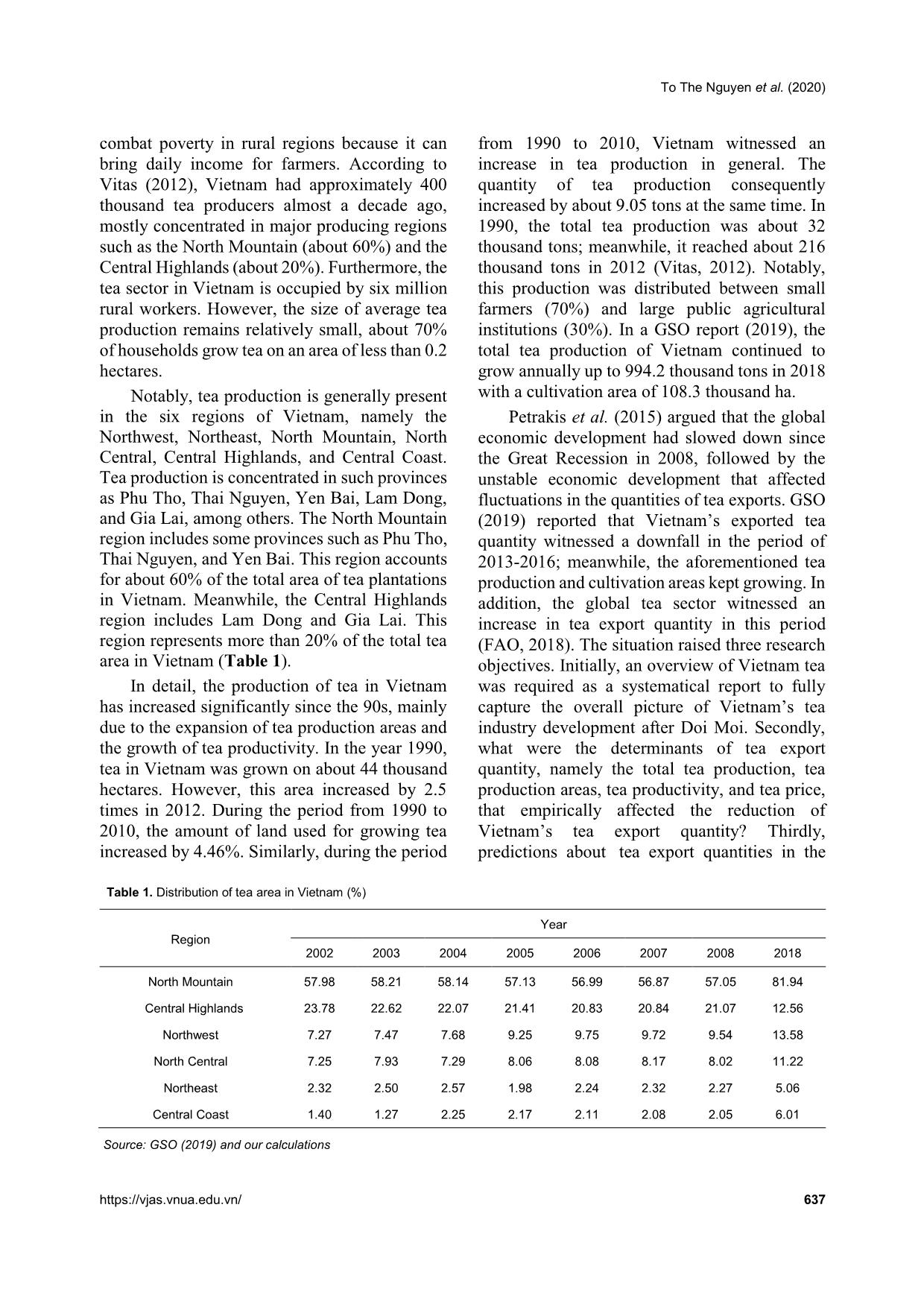

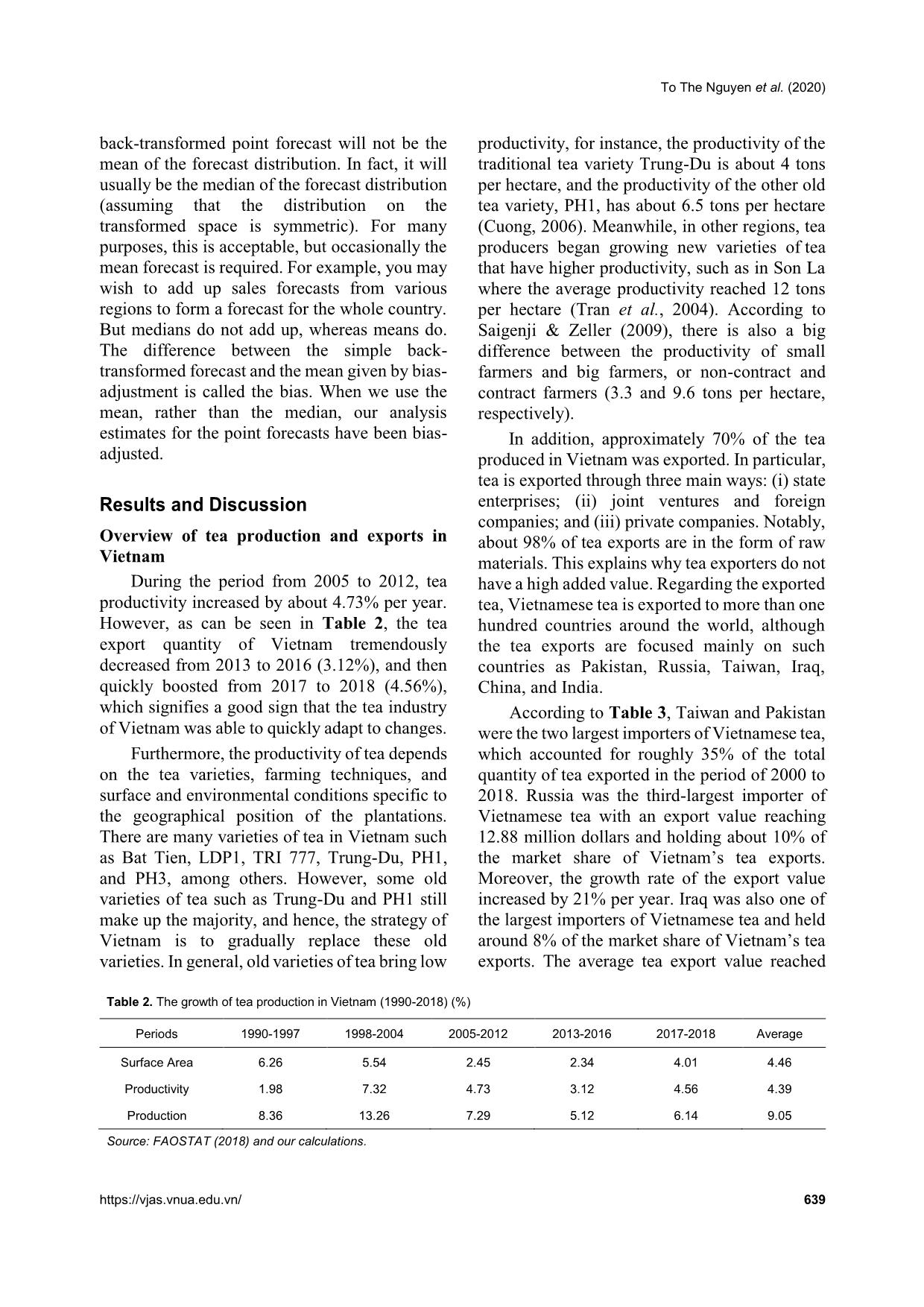

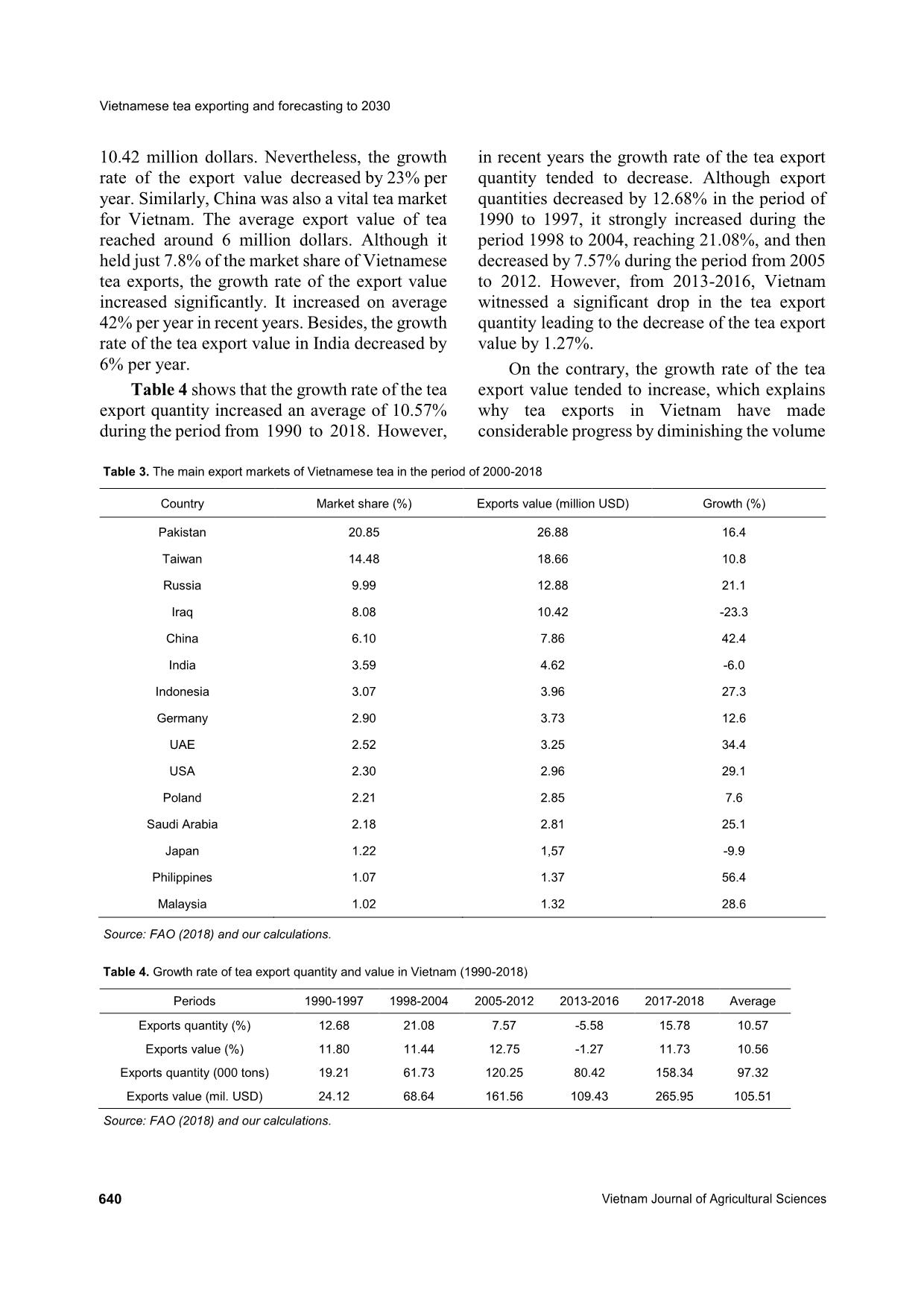

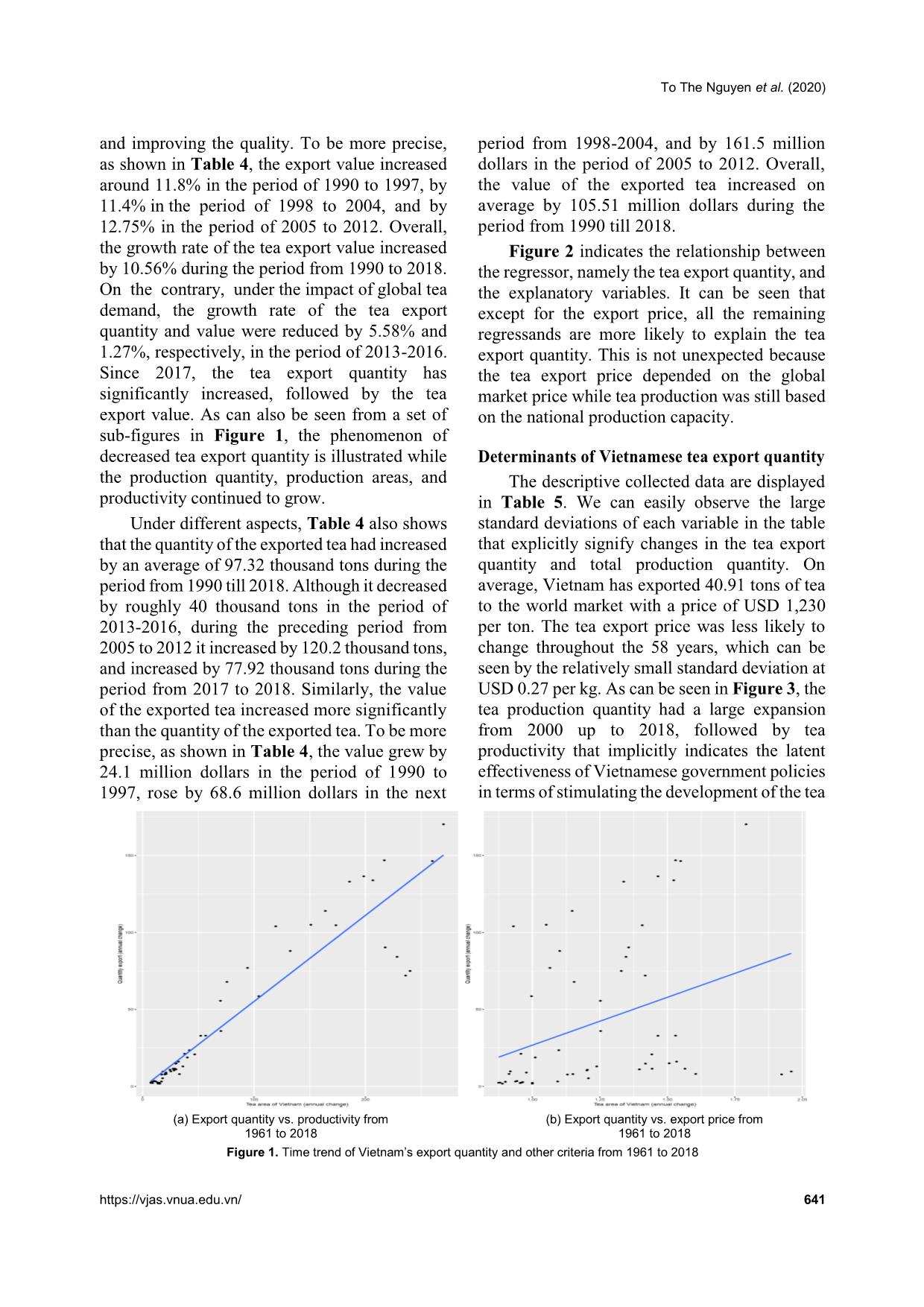

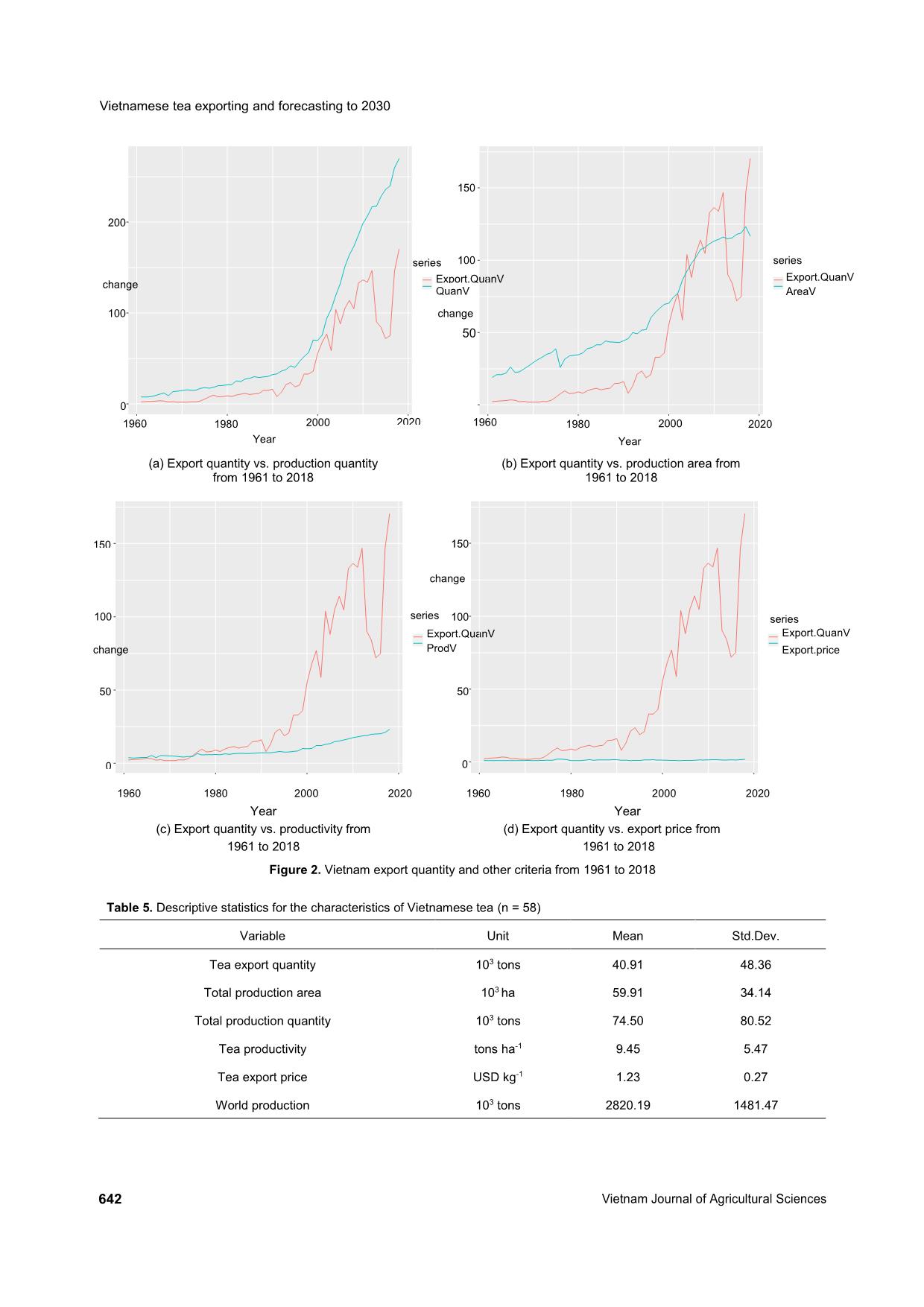

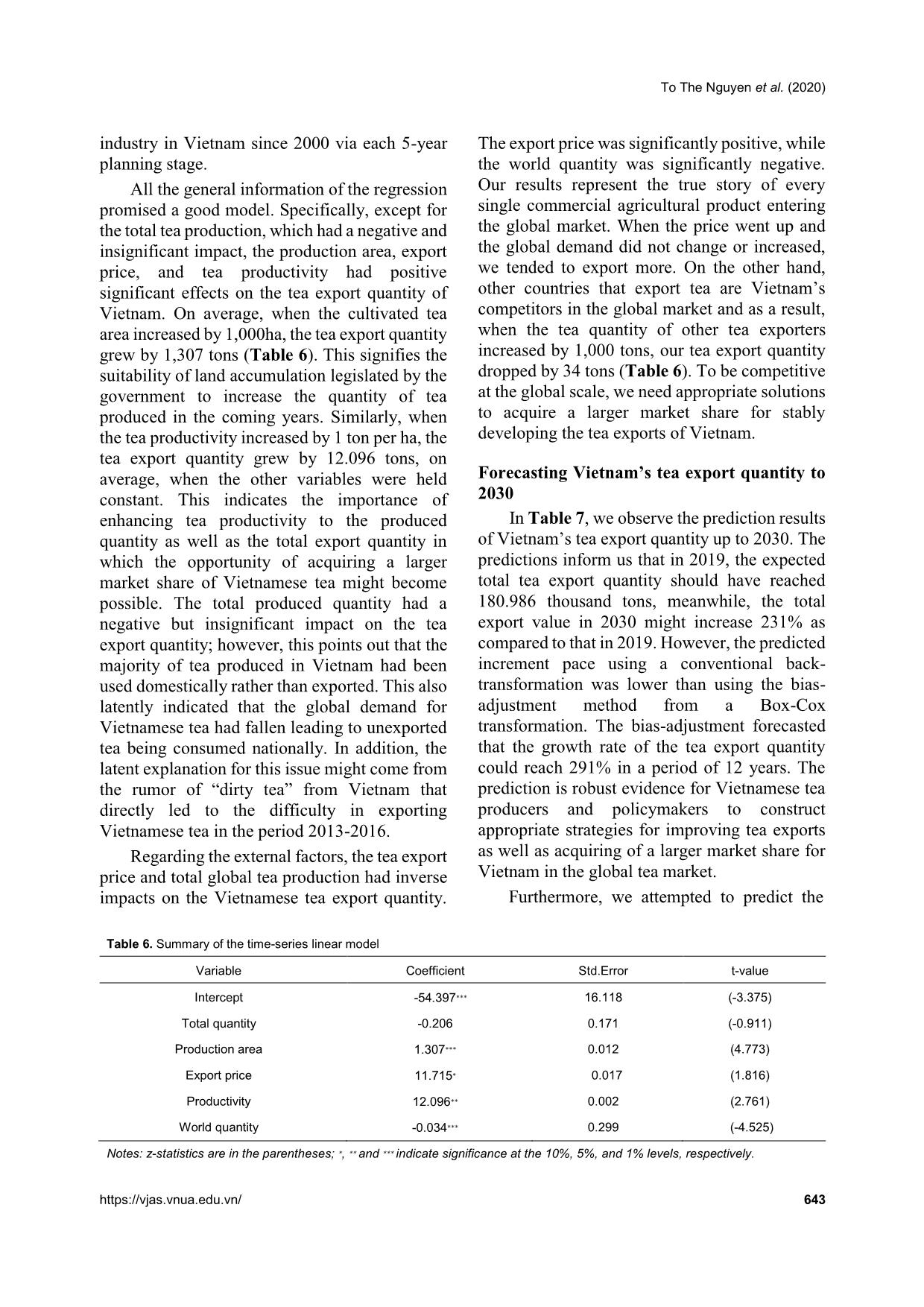

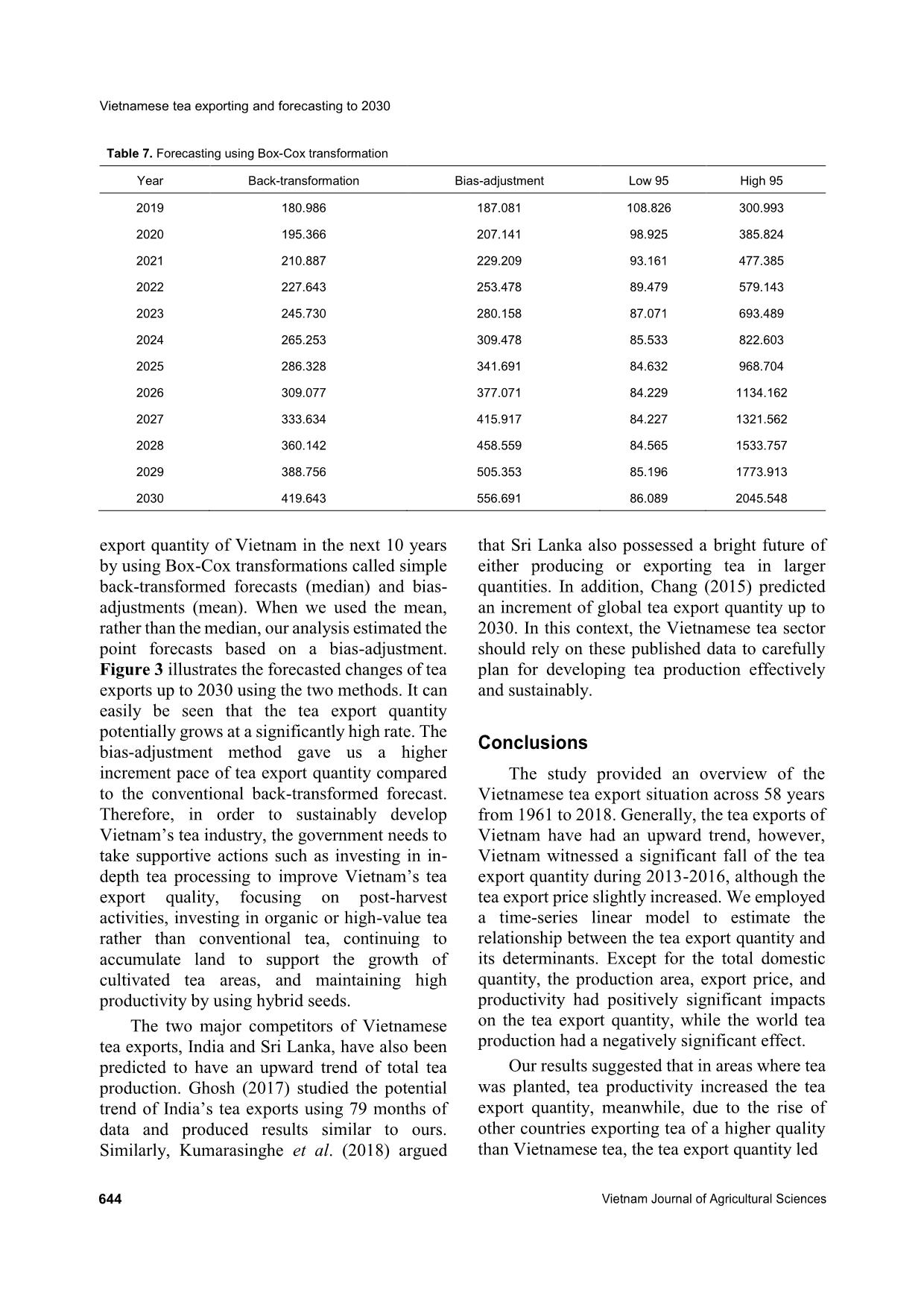

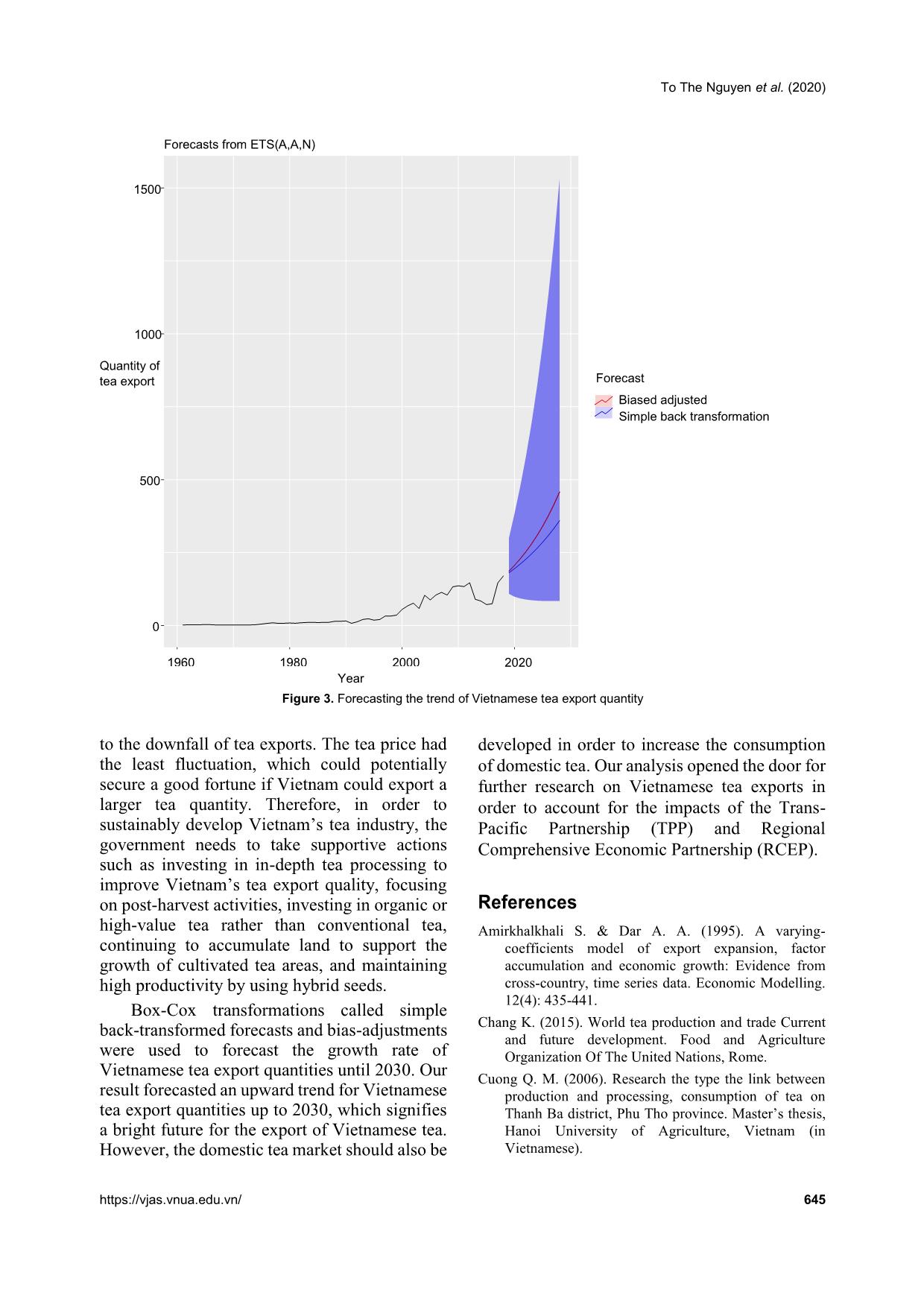

of 2013-2016, during the preceding period from 2005 to 2012 it increased by 120.2 thousand tons, and increased by 77.92 thousand tons during the period from 2017 to 2018. Similarly, the value of the exported tea increased more significantly than the quantity of the exported tea. To be more precise, as shown in Table 4, the value grew by 24.1 million dollars in the period of 1990 to 1997, rose by 68.6 million dollars in the next period from 1998-2004, and by 161.5 million dollars in the period of 2005 to 2012. Overall, the value of the exported tea increased on average by 105.51 million dollars during the period from 1990 till 2018. Figure 2 indicates the relationship between the regressor, namely the tea export quantity, and the explanatory variables. It can be seen that except for the export price, all the remaining regressands are more likely to explain the tea export quantity. This is not unexpected because the tea export price depended on the global market price while tea production was still based on the national production capacity. Determinants of Vietnamese tea export quantity The descriptive collected data are displayed in Table 5. We can easily observe the large standard deviations of each variable in the table that explicitly signify changes in the tea export quantity and total production quantity. On average, Vietnam has exported 40.91 tons of tea to the world market with a price of USD 1,230 per ton. The tea export price was less likely to change throughout the 58 years, which can be seen by the relatively small standard deviation at USD 0.27 per kg. As can be seen in Figure 3, the tea production quantity had a large expansion from 2000 up to 2018, followed by tea productivity that implicitly indicates the latent effectiveness of Vietnamese government policies in terms of stimulating the development of the tea (a) Export quantity vs. productivity from 1961 to 2018 (b) Export quantity vs. export price from 1961 to 2018 Figure 1. Time trend of Vietnam’s export quantity and other criteria from 1961 to 2018 Vietnamese tea exporting and forecasting to 2030 642 Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Sciences 1960 1980 2000 2020 Year (c) Export quantity vs. productivity from 1961 to 2018 1960 1980 2000 2020 Year (d) Export quantity vs. export price from 1961 to 2018 Figure 2. Vietnam export quantity and other criteria from 1961 to 2018 Table 5. Descriptive statistics for the characteristics of Vietnamese tea (n = 58) Variable Unit Mean Std.Dev. Tea export quantity 103 tons 40.91 48.36 Total production area 103 ha 59.91 34.14 Total production quantity 103 tons 74.50 80.52 Tea productivity tons ha-1 9.45 5.47 Tea export price USD kg-1 1.23 0.27 World production 103 tons 2820.19 1481.47 0 100 200 1960 1980 2000 2020 Year change series QuanV Export.QuanV 0 50 100 150 1960 1980 2000 2020 Year change series Export.QuanV AreaV (a) Export quantity vs. production quantity from 1961 to 2018 (b) Export quantity vs. production area from 1961 to 2018 0 50 100 150 change series ProdV Export.QuanV 0 50 100 150 change series Export.QuanV Export.price To The Nguyen et al. (2020) https://vjas.vnua.edu.vn/ 643 industry in Vietnam since 2000 via each 5-year planning stage. All the general information of the regression promised a good model. Specifically, except for the total tea production, which had a negative and insignificant impact, the production area, export price, and tea productivity had positive significant effects on the tea export quantity of Vietnam. On average, when the cultivated tea area increased by 1,000ha, the tea export quantity grew by 1,307 tons (Table 6). This signifies the suitability of land accumulation legislated by the government to increase the quantity of tea produced in the coming years. Similarly, when the tea productivity increased by 1 ton per ha, the tea export quantity grew by 12.096 tons, on average, when the other variables were held constant. This indicates the importance of enhancing tea productivity to the produced quantity as well as the total export quantity in which the opportunity of acquiring a larger market share of Vietnamese tea might become possible. The total produced quantity had a negative but insignificant impact on the tea export quantity; however, this points out that the majority of tea produced in Vietnam had been used domestically rather than exported. This also latently indicated that the global demand for Vietnamese tea had fallen leading to unexported tea being consumed nationally. In addition, the latent explanation for this issue might come from the rumor of “dirty tea” from Vietnam that directly led to the difficulty in exporting Vietnamese tea in the period 2013-2016. Regarding the external factors, the tea export price and total global tea production had inverse impacts on the Vietnamese tea export quantity. The export price was significantly positive, while the world quantity was significantly negative. Our results represent the true story of every single commercial agricultural product entering the global market. When the price went up and the global demand did not change or increased, we tended to export more. On the other hand, other countries that export tea are Vietnam’s competitors in the global market and as a result, when the tea quantity of other tea exporters increased by 1,000 tons, our tea export quantity dropped by 34 tons (Table 6). To be competitive at the global scale, we need appropriate solutions to acquire a larger market share for stably developing the tea exports of Vietnam. Forecasting Vietnam’s tea export quantity to 2030 In Table 7, we observe the prediction results of Vietnam’s tea export quantity up to 2030. The predictions inform us that in 2019, the expected total tea export quantity should have reached 180.986 thousand tons, meanwhile, the total export value in 2030 might increase 231% as compared to that in 2019. However, the predicted increment pace using a conventional back- transformation was lower than using the bias- adjustment method from a Box-Cox transformation. The bias-adjustment forecasted that the growth rate of the tea export quantity could reach 291% in a period of 12 years. The prediction is robust evidence for Vietnamese tea producers and policymakers to construct appropriate strategies for improving tea exports as well as acquiring of a larger market share for Vietnam in the global tea market. Furthermore, we attempted to predict the Table 6. Summary of the time-series linear model Variable Coefficient Std.Error t-value Intercept -54.397∗∗∗ 16.118 (-3.375) Total quantity -0.206 0.171 (-0.911) Production area 1.307∗∗∗ 0.012 (4.773) Export price 11.715∗ 0.017 (1.816) Productivity 12.096∗∗ 0.002 (2.761) World quantity -0.034∗∗∗ 0.299 (-4.525) Notes: z-statistics are in the parentheses; ∗, ∗∗ and ∗∗∗ indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. Vietnamese tea exporting and forecasting to 2030 644 Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Sciences Table 7. Forecasting using Box-Cox transformation Year Back-transformation Bias-adjustment Low 95 High 95 2019 180.986 187.081 108.826 300.993 2020 195.366 207.141 98.925 385.824 2021 210.887 229.209 93.161 477.385 2022 227.643 253.478 89.479 579.143 2023 245.730 280.158 87.071 693.489 2024 265.253 309.478 85.533 822.603 2025 286.328 341.691 84.632 968.704 2026 309.077 377.071 84.229 1134.162 2027 333.634 415.917 84.227 1321.562 2028 360.142 458.559 84.565 1533.757 2029 388.756 505.353 85.196 1773.913 2030 419.643 556.691 86.089 2045.548 export quantity of Vietnam in the next 10 years by using Box-Cox transformations called simple back-transformed forecasts (median) and bias- adjustments (mean). When we used the mean, rather than the median, our analysis estimated the point forecasts based on a bias-adjustment. Figure 3 illustrates the forecasted changes of tea exports up to 2030 using the two methods. It can easily be seen that the tea export quantity potentially grows at a significantly high rate. The bias-adjustment method gave us a higher increment pace of tea export quantity compared to the conventional back-transformed forecast. Therefore, in order to sustainably develop Vietnam’s tea industry, the government needs to take supportive actions such as investing in in- depth tea processing to improve Vietnam’s tea export quality, focusing on post-harvest activities, investing in organic or high-value tea rather than conventional tea, continuing to accumulate land to support the growth of cultivated tea areas, and maintaining high productivity by using hybrid seeds. The two major competitors of Vietnamese tea exports, India and Sri Lanka, have also been predicted to have an upward trend of total tea production. Ghosh (2017) studied the potential trend of India’s tea exports using 79 months of data and produced results similar to ours. Similarly, Kumarasinghe et al. (2018) argued that Sri Lanka also possessed a bright future of either producing or exporting tea in larger quantities. In addition, Chang (2015) predicted an increment of global tea export quantity up to 2030. In this context, the Vietnamese tea sector should rely on these published data to carefully plan for developing tea production effectively and sustainably. Conclusions The study provided an overview of the Vietnamese tea export situation across 58 years from 1961 to 2018. Generally, the tea exports of Vietnam have had an upward trend, however, Vietnam witnessed a significant fall of the tea export quantity during 2013-2016, although the tea export price slightly increased. We employed a time-series linear model to estimate the relationship between the tea export quantity and its determinants. Except for the total domestic quantity, the production area, export price, and productivity had positively significant impacts on the tea export quantity, while the world tea production had a negatively significant effect. Our results suggested that in areas where tea was planted, tea productivity increased the tea export quantity, meanwhile, due to the rise of other countries exporting tea of a higher quality than Vietnamese tea, the tea export quantity led To The Nguyen et al. (2020) https://vjas.vnua.edu.vn/ 645 Figure 3. Forecasting the trend of Vietnamese tea export quantity to the downfall of tea exports. The tea price had the least fluctuation, which could potentially secure a good fortune if Vietnam could export a larger tea quantity. Therefore, in order to sustainably develop Vietnam’s tea industry, the government needs to take supportive actions such as investing in in-depth tea processing to improve Vietnam’s tea export quality, focusing on post-harvest activities, investing in organic or high-value tea rather than conventional tea, continuing to accumulate land to support the growth of cultivated tea areas, and maintaining high productivity by using hybrid seeds. Box-Cox transformations called simple back-transformed forecasts and bias-adjustments were used to forecast the growth rate of Vietnamese tea export quantities until 2030. Our result forecasted an upward trend for Vietnamese tea export quantities up to 2030, which signifies a bright future for the export of Vietnamese tea. However, the domestic tea market should also be developed in order to increase the consumption of domestic tea. Our analysis opened the door for further research on Vietnamese tea exports in order to account for the impacts of the Trans- Pacific Partnership (TPP) and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). References Amirkhalkhali S. & Dar A. A. (1995). A varying- coefficients model of export expansion, factor accumulation and economic growth: Evidence from cross-country, time series data. Economic Modelling. 12(4): 435-441. Chang K. (2015). World tea production and trade Current and future development. Food and Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations, Rome. Cuong Q. M. (2006). Research the type the link between production and processing, consumption of tea on Thanh Ba district, Phu Tho province. Master’s thesis, Hanoi University of Agriculture, Vietnam (in Vietnamese). 0 500 1000 1500 1960 1980 2000 2020 Year Quantity of tea export Forecast Biased adjusted Simple back transformation Forecasts from ETS(A,A,N) Vietnamese tea exporting and forecasting to 2030 646 Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Sciences FAO (2019). FAOSTAT. Retrieved on May 5, 2019 at Ghosh S. (2017). Forecasting Exports of Tea from India: Application of Arima Model. Journal of Commerce and Trade. 12(2): 116-129. GSO (2019). Statistical summary book of Vietnam 2018. General Statistics Office (in Vietnamese). Kingu J. (2016): Determinants of Export Performance of Tea in Tanzania: Parametric and Non-Parametric Analysis. Amity Business Review. 11(7): 173-183. Kumarasinghe H. P. A. S. S. & Peiris B. L. (2018). Forecasting annual tea production in Sri Lanka. Tropical Agricultural Research. 29(2): 184-193. Miano G. W. (2010). Determinants of tea export supply in Kenya (1970-2007). Ph.D. thesis, University of Nairobi, Kenya. Petrakis P. E., Kostis P. C. & Valsamis D. G. (2015). Innovation and competitiveness: Culture as a long- term strategic instrument during the European Great Recession. Journal of Business Research. 68(7): 1436-1438. Saigenji Y. & Zeller M. (2009). Effect of contract farming on productivity and income of small holders: The case of tea production in north-western Vietnam. International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, Beijing, China - September 2009. Serletis A. (1992): Export growth and Canadian economic development. Journal of Development Economics. 38(1): 133-145. Tran T. C., Samman E. & Rich K. (2004). The participation of the poor in agricultural value chains: A case study of tea. Asian Development Bank, Hanoi, Vietnam - October 2004. Tuan A. N. & Nguyen T. T. (2019). Efficiency and adoption of organic tea production: Evidence from Vi Xuyen district, Ha Giang province, Vietnam. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science. 3(1): 201-217. Uk Polo V. (1994). Export composition and growth of selected low-income African countries: Evidence from time-series data. Applied Economics. 26(5): 445-449. Vitas (2012). The 2011 Vietnam Handbook of Tea. Vietnam Tea Association, Hanoi, Vietnam (in Vietnamese).

File đính kèm:

vietnamese_tea_exporting_and_forecasting_to_2030.pdf

vietnamese_tea_exporting_and_forecasting_to_2030.pdf