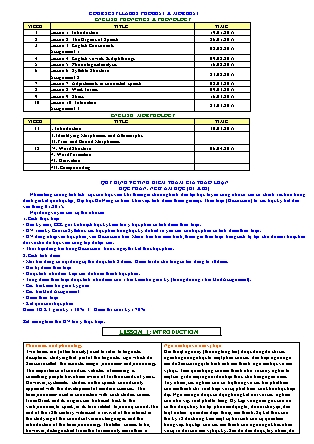

Tài liệu học phần Ngữ âm học (B1 & B2)

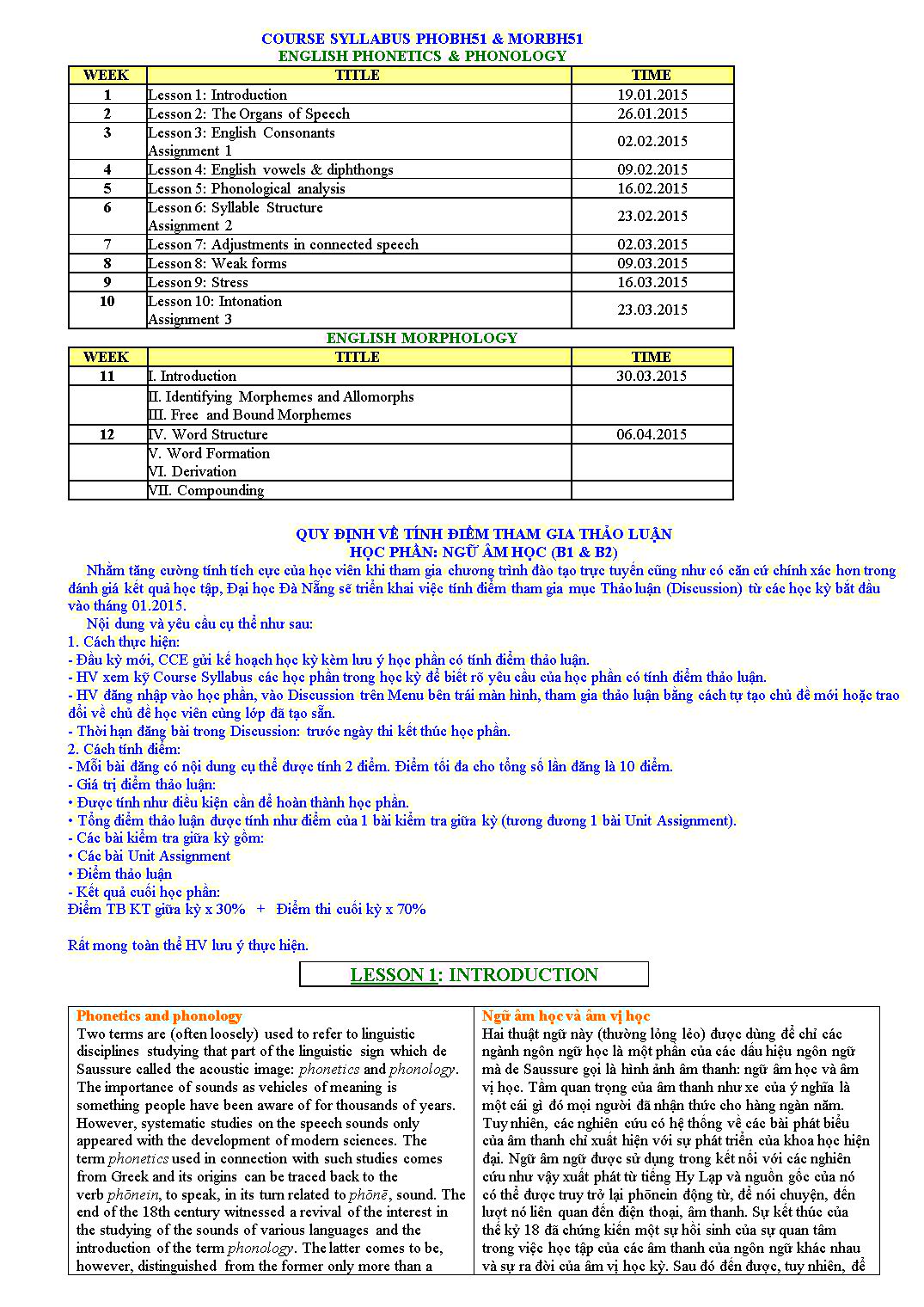

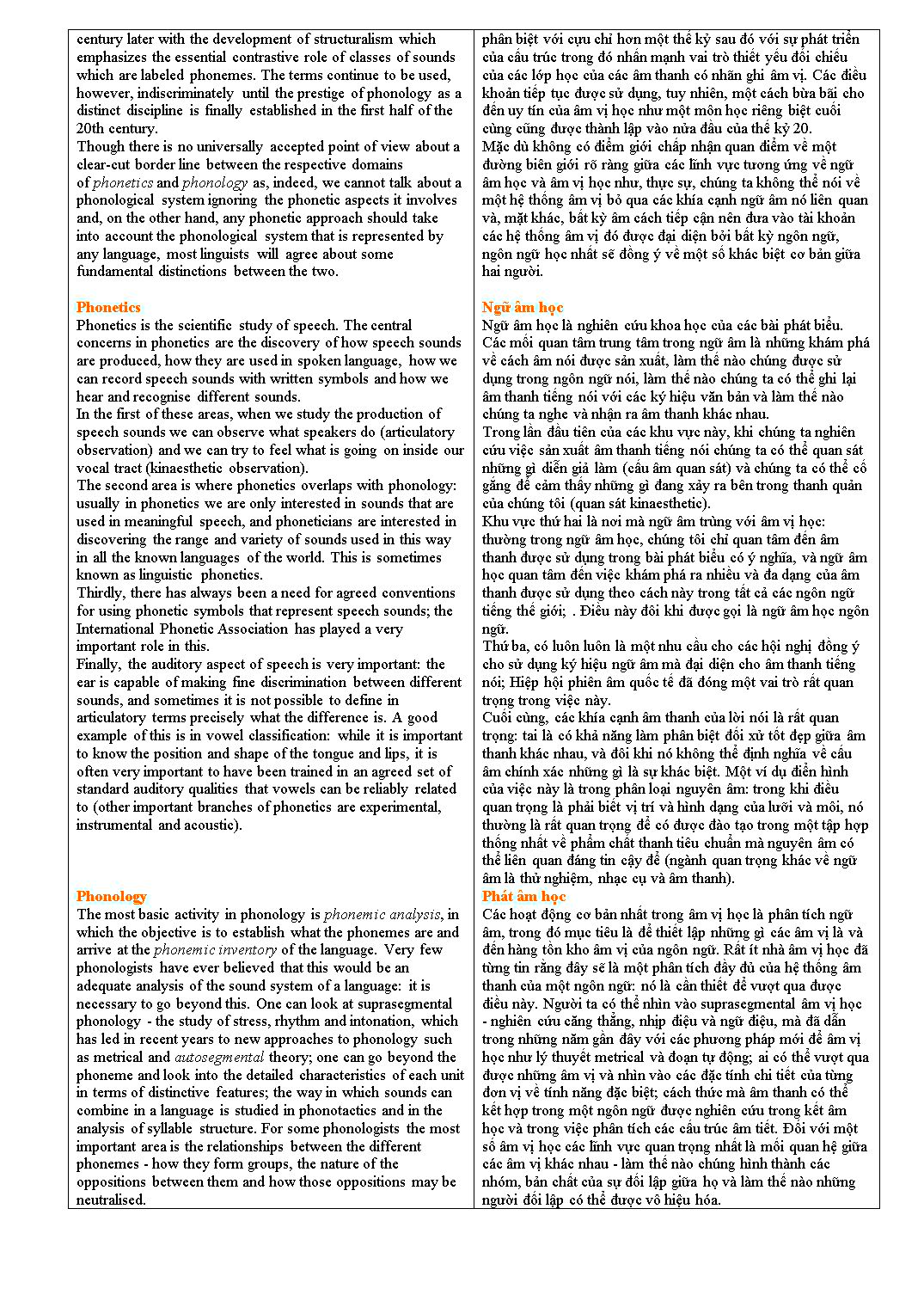

Phonetics and phonology

Two terms are (often loosely) used to refer to linguistic disciplines studying that part of the linguistic sign which de Saussure called the acoustic image: phonetics and phonology. The importance of sounds as vehicles of meaning is something people have been aware of for thousands of years. However, systematic studies on the speech sounds only appeared with the development of modern sciences. The term phonetics used in connection with such studies comes from Greek and its origins can be traced back to the verb phōnein, to speak, in its turn related to phōnē, sound. The end of the 18th century witnessed a revival of the interest in the studying of the sounds of various languages and the

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Tài liệu học phần Ngữ âm học (B1 & B2)

derived form is a verbs capable of taking the normal past tense ending. Table 4.5 Some examples of conversion Noun Derived verb Verb Derived noun father butter ship nail brush father butter ship nail brush subjéct contést survéy permít condúct súbject cóntest súrvey pérmit cónduct He fathered three children. He buttered the bread. Conversion is usually restricted to unsuffixes words, although there are a few exceptions such as propos-ition (noun to verb), refer-ee (noun to verb), and dirt-y (adjective to verb). Another device is ablaut, the replacement of a vowel with a different vowel (see Table 4.6). Ablaut was frequent in early stages of English and in related ancient languages. Vestiges remain in Modern English. Though the process is no longer productive (used in forming new words). Table 4.6 Some examples of ablaut Verb stem Ablaut noun sing abide shoot sell song adobe shot sale Stress shift is used in English to mark the difference between related nouns and verbs. We have already seen some examples of this in Table 4.5. Generally, the verbs have final stress, while the nouns have initial stress, as the further examples in Table 4.7 illustrate. Table 4.7 Nouns and verbs that differ only in stress. Noun Verb cómbine tórment ímpiant rétest combíne tormént impiánt retést Nonaffixal morphology is common in other languages and may involve vocalic patterns or tone and other suprasegmental phonological features, sometimes in complex ways. Word-based Morphology in English, the stem of a new word is almost invariably existing word. For this reason, we say that English morphology is word-based: words are built on words. As we saw in the case of the complex word denationalization. Each affix is added successively to an English word. There are, however, many English words whose stems, when the outer affixes are removed, are not existing English words. Consider the words recalcitrant, horrible, anduncouth. These are all English words, but when the affixes re-, -ible, and un- are removed, we are left with the stems *calcitrant, *horr and *couth, which are not English words. In all three cases, the reasons for the anomaly are historical. Recalcitrant and horrible were borrowed in their entirety from Latin and French. Because the affixes re-and -ible were also borrowed, these words appear to have been formed by means of English morphology, although they were not. English has many words like these two, borrowed from the Romance languages, from which many productive English affixes have also been borrowed. Many of them have nonword stems for the same reason. Uncouth is not borrowed, but was formed many centuries ago from the then existing word couth(historically related to can and know and still found in some British dialects). Some time after uncouth was formed, couth disappeared from most dialects, including the standard, leaving uncouth stranded without a stem. Grateful is another example of the same phenomenon. Words like grateful and horrible maybe described as having bound stems; in any case, they can be explained as cases of historical accident. When we understand how such exceptional words arose, it remains true that that all productive English word formation is word-based. Whether all languages are like English in this respect is still an open question. Some Problematic Cases: It is not always easy to determine a word’s internal structure. In the case of words such as cranberry and huckleberry, it is tempting to assume that the root is berry, but this leaves us with the morphemes cran- and huckle-. These elements are obviously not affixes like un- or re- since they occur with only one root. At the same time, however, neither cran- nor huckle- can be considered a free morpheme since neither ever stands alone as an independent word. The status of such morphemes continues to be problematic for linguists, who generally classify them as exceptional cases (or refer to them as cranberry morphemes). A slightly different problem arises in the case of words such as receive, deceive, conceive, and perceive or permit, submit, and commit. The apparent affixes in these words do not express the same meaning as they do when they are attached to a free morpheme. Thus, the re- of receive, for example, does not have the sense of ‘again’ that it does in redo (‘do again’). Nor does the de- of deceive appear to express the meaning ‘reverse the process of’ associated with the affix in demystify or decertify. Moreover, the other portions of these words (ceive and mit) have no identifiable meaning either. Because they have no meaning, ceive and mit are not morphemes of a normal sort. However, they have do have some interesting properties. For example, when certain suffixes are added to words ending in ceive, ceive quite regularly becomes cept (as in ‘receptive, deception’); similarly, mit becomes miss when the same suffixes are added (permissive, admission). These changes are not phonologically determined, since the ssdoes not occur before these suffixes in other words ending in t (prohibitive, edition). The changes must therefore be due to idiosyncratic properties of mit and ceive, similar to those of the morpheme man, whose plural is always men rather than the expected mans (postmen, brakemen, and so on). Mit and ceive are thus very similar to morphemes. V. WORD FORMATION A characteristic of all human languages is the potential to create new words. The categories of noun, verb, adjective, and adverb are open in the sense that new members are constantly being added. The two most common types of word formation arederivation and compounding, both of which create new words from already existing morphemes. Derivation is the process by which a new word is built from a base, usually through the addition of an affix. Compounding, on the other hands, is a process involving the combination of two words (with or without accompanying affixes) to yield a new word. The noun helper, for example, is related to the verb help via derivation, the compound word mailbox, in contrast, is created from the words mail and box. 1. Derivation Derivation creates a new word by changing the category and/or the meaning of the base to which it applies. The derivation affix -er, for instance, combines with a verb to create a noun with the meaning ‘one who does X’, as shown in Figure 5.1. 1.1. English Derivational Affixes English makes very widespread use of derivation. Table 5.1 lists some examples of English derivational affixes, along with information about the type of base with which they combine and the type of category that results. The first entry states that the affix -able applies to a verb base and converts it into an adjective with the meaning ‘able to be X’ed’. Thus if we add the affix -able to the verb fix, we get an adjective with the meaning ‘able to be fixed’. 1.2. Derivational Rules Each line in Table 5.1 can be thought of as a word formation rule that predicts how words may be formed in English. Thus, if there is a rule whereby the prefix un- may be added to an adjective X, resulting in another adjective, unX, with the meaning ‘not X’, then we predict that an adjective like harmonious may be combines with this prefix to form the adjective unharmonious, which will mean ‘not harmonious’. The rule also provides a structure to the word, given in Figure 5.2. These rules have another function: they may be used to analyze word, as well as to form them. Suppose, for example, that we come across the word unharmonious in a book on architecture. Even though we may never have encountered this word before, we will probably not notice its novelty, but simply use our unconscious knowledge of English word formation to process its meaning, in fact, many of the words that we encounter in reading, especially in technical literature, are novel, but we seldom have to look them up, relying instead on our morphological competence. Sometimes beginning students have trouble determining the category of the base to which an affix is added. In the case of worker, for instance, the base (work) is sometimes used as a verb (as in they work hard) and sometimes as a noun (as in the work is time-consuming). This may then make it difficult to know which category occurs with the suffix -er in the word worker. The solution to this problem is to consider the use of -er (in the sense of ‘one who X’s’) with bases whose category can be unequivocally determined. In the words teacher and writer, for instance, we see this affix used with bases (teach and write) that are clearly verbs. Moreover, we know that -er can combine with the verb sell (seller) but not the noun sale (*saler). These facts allow us to conclude that the base with which -er combines in the word worker must be a verb rather than a noun. 1.3. Multiple Derivations Derivation can create multiple levels of word structure, as shown in Figure 5.3. although complex ‘organizational’ has a structure consistent with the word formation rules given in Table 5.1. Starting with the outermost affix, we see that -al forms adjectives from nouns,-ation forms nouns from verbs, and -ize forms verbs from nouns. Table 5.2 Distribution of un- un + A un + N unable unkind unhurt *unknowledge *unintelligence *uninjury In some cases, the internal structure of a complex word is not obvious. The wordunhappiness, for instance, could apparently be analyzed in either of the ways indicated in Figure 5.4. by considering the properties of the affixes un- and ness-, however, it is possible to find an argument that favors Figure 5.4a over 5.4b. The key observation here is that the prefix un- combines quite freely with adjectives, but not with nouns as shown in Table 5.2. (The advertiser’s uncola is an exception to this rule and therefore attracts the attention of the reader or listener). This suggests that un- must combine with the adjective happy before it is converted into a noun by the suffix -ness - exactly what the structure in Figure 5.4a depicts. The derivation of this word therefore proceeds in two steps. First, the prefix un- is attached to the adjective happy, resulting in another adjective (see Figure 5.5). The second step is to add the suffix -ness to this adjective (see Figure 5.6). We see, then, that complex words have structures consisting of hierarchically organized constituents. The same is true of sentences, when we study further. Table 5.3 Restrictions on the use of -en Acceptable Unacceptable whiten soften madden quicken liven *abstracten *bluen *angryen *slowen *greenen 1.4. A phonological constraint (advanced) Derivation does not always apply freely to the members of a given category. Sometimes, for instance, a particular derivational affix is able to attach only to stems with particular phonological properties. A good example of this involves the English suffix -en, which combines with adjectives to create verbs with a causative meaning (‘cause to become X’). as the following examples illustrate, however, there are many adjectives with which-en cannot combine. The suffix -en is subject to a phonological constraint. In particular, it can only combine with a monosyllabic stem that ends in an obstruent. Hence it can be added to white, which is both monosyllabic and ends in an obstruent, but not to abstract, which has two syllables, or to blue, which does not end in an obstruent. 2. Compounding In derivational word formation, we take a single word and change it somehow, usually by adding an affix, to form a new word. The other way to form is by combining two already existing words in a compound. Blackbird, doghouse, seaworthy, and blue-green are examples of compounds. Compounding is highly productive in English and in related languages such as German. It is also widespread throughout the languages of the world. In English, compounds can be found in all the major lexical categories -nouns (doorstop), adjectives (winedark), and verbs (stagemanage) - but nouns are by far the most common type of compounds. Verbs compounds are quite infrequent. Among noun compounds, most are of the form noun + noun (N N), but adjective + noun (A N) compounds are also found quite frequently; verb + noun (V N) compounds are rare. An example of each type is given in Figure 5.7. Compound adjectives are of the type adjective + adjective (A A) or noun + adjective (N A), as shown in Figure 5.8. Although there are very few true compound verbs in English, this does not seem to be due to any general principles. In other languages, compound verbs are quite common. Structurally, two features of compounds stand out. One is the fact that the constituent members of a compound are not equal. In all the examples given thus far, the lexical category of the last member of the compound is the same as that of the entire compound. Furthermore, the first member ia always a modifier of the second: steamboat is a type of boat; red-hot is a degree of hotness. In other words, the second member acts as the head of the compound, from which most of the syntactic properties of the compound are derived, while the first member is its dependent. This is generally true in English and in many other languages, although there are also languages in which the first member of a compound is the head. The second structural peculiarity of compounds, which is true of all languages of the world, is that a compound never has more than two constituents. This is not to say that a compound may never contain more than two words. Three-word (dog food box), four-word (stone age cave dweller), and longer compounds (trade union delegate assembly leader) are easy to find. But in each case, the entire compound always consists of two components, each of which may itself be a compound, as shown in Figure 5.9. the basic compounding operation is therefore always binary, although repetition of the basic operation may result in more complex individual forms. Compounding and derivation may also feed each other. The members of a compound are often themselves derivationally complex, and sometimes, though not often. A compound may serve as the base of a derivational affix. An example of each of these situations is given in Figure 5.10. English orthography is not consistent in representing compounds since they are sometimes written as single words, sometimes with an intervening hyphen, and sometimes as separate words. However, it is usually possible to recognize noun compounds by their stress pattern since the first component is pronounced more prominently than the second. In noncompounds, conversely, the second element is stressed (see Table 5.4). Although the exact types of compounds differ from language to language, the practice of combining two existing words to create a new word is very widespread. ;–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––; GOOD LUCK TO YOU!

File đính kèm:

tai_lieu_hoc_phan_ngu_am_hoc_b1_b2.doc

tai_lieu_hoc_phan_ngu_am_hoc_b1_b2.doc