Production efficiency analysis of indigenous pig production in Northwest Vietnam

This research was conducted to investigate the production efficiency

of Ban pig production in northwest Vietnam between October 2016

and January 2017. Primary data obtained from 171 producers were

analyzed by applying cost-benefit analysis and stochastic frontier

production function. The benefit-cost ratio per litter was 1.24,

indicating that the enterprise was profitable. Compared to other

farms, the farms focused on farrow-to-finisher attained the highest

net return (EUR 213.71/litter), while inputs were used most

effectively by the mixed farms. The results from the Cobb-Douglas

production function revealed that labour, feeding costs, stocking

density, and pigpen structure had positive effects on the production

output. Additionally, farms with the phase of farrow-to-nursery

obtained less total revenue, while farms focused on the farrow-tofinisher phase achieved higher production outputs than the mixed

farms. The level of technical efficiency for each farm ranged between

0.62 and 0.98, with a mean of 0.88. The number of live-born piglets

and depreciation cost had positive effects, whereas the nursery

interval had a negative impact on the technical efficiency. Ban pig

producers could increase technical efficiency by efficiently utilizing

available resources and improving managerial skills.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Production efficiency analysis of indigenous pig production in Northwest Vietnam

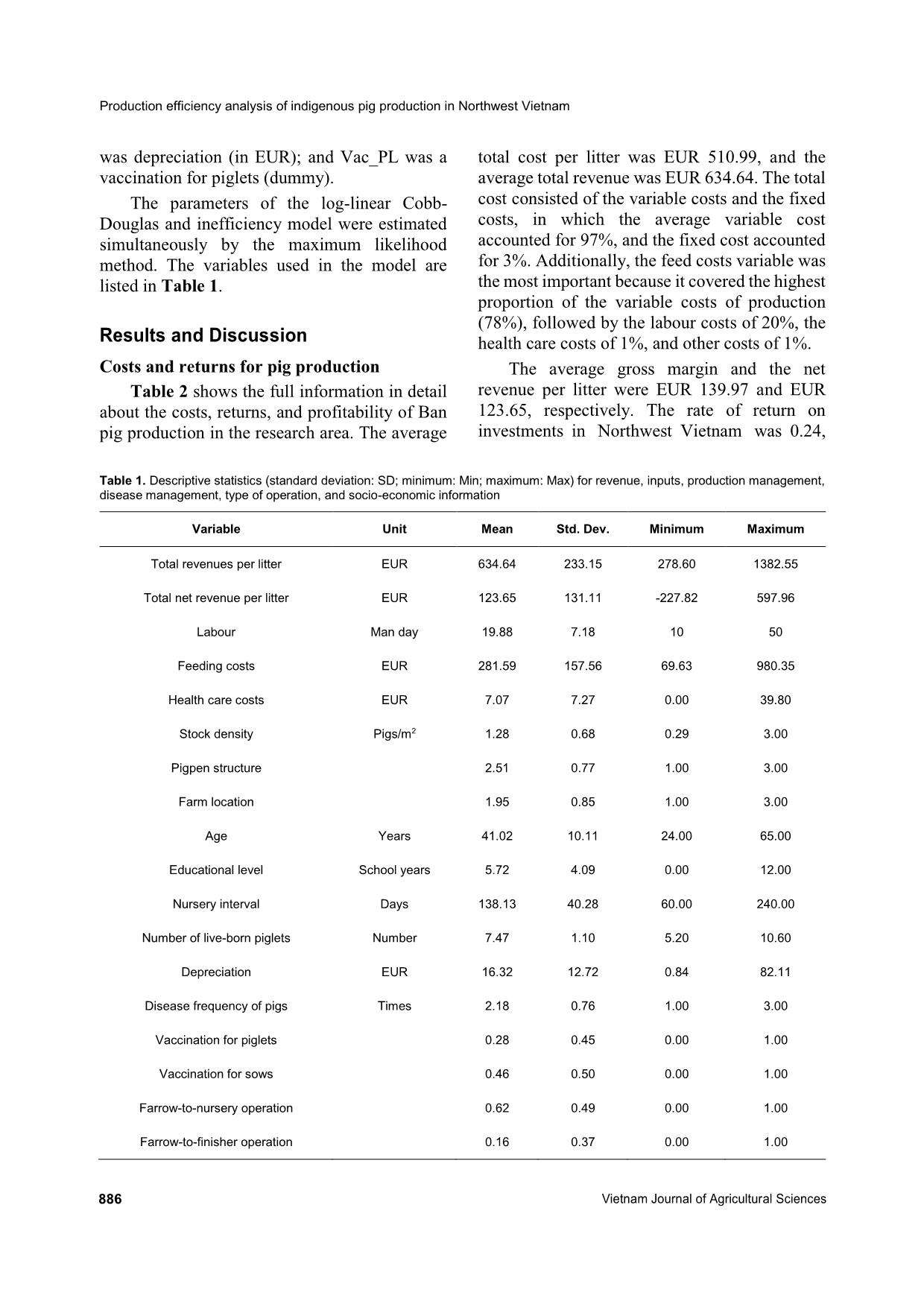

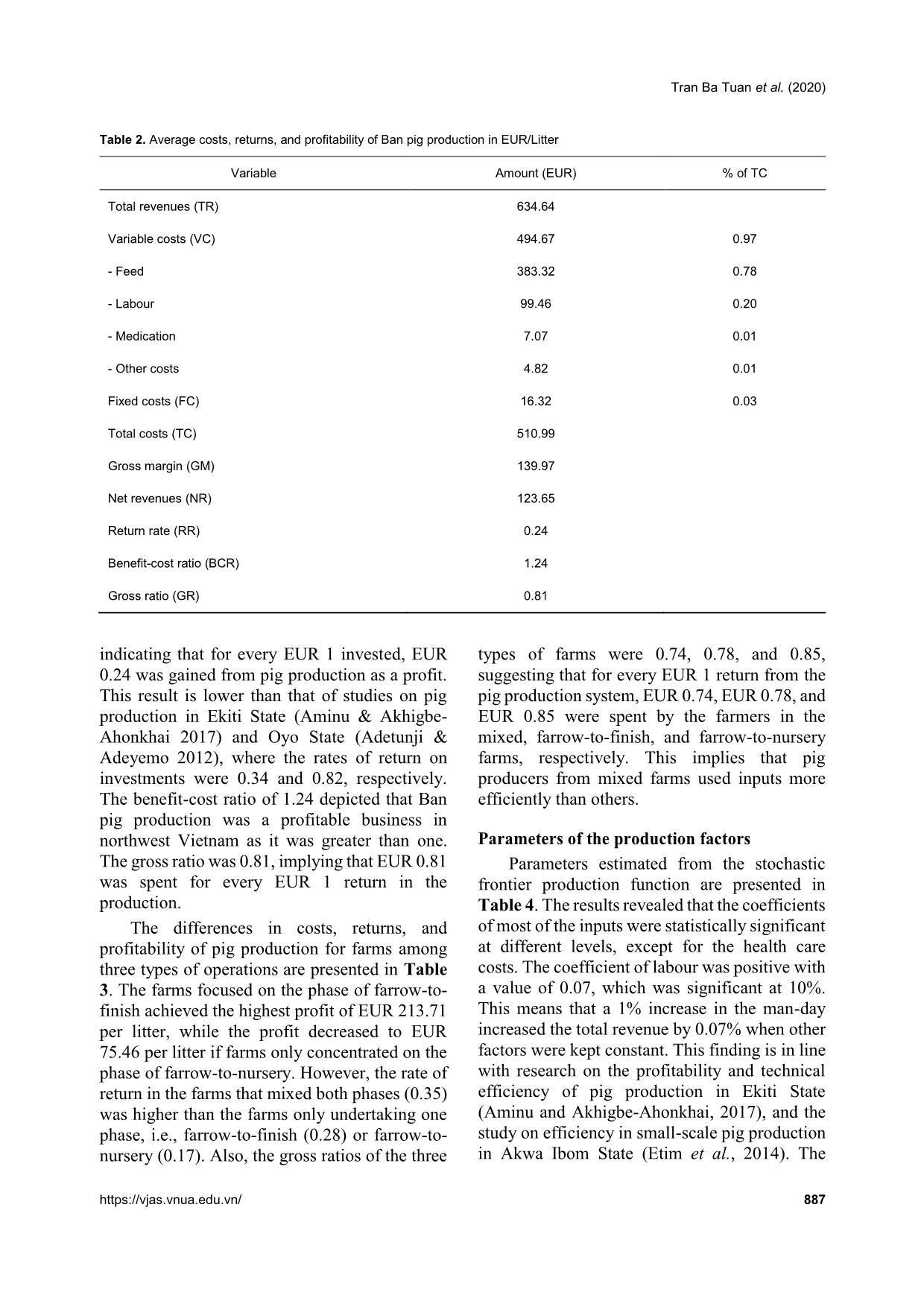

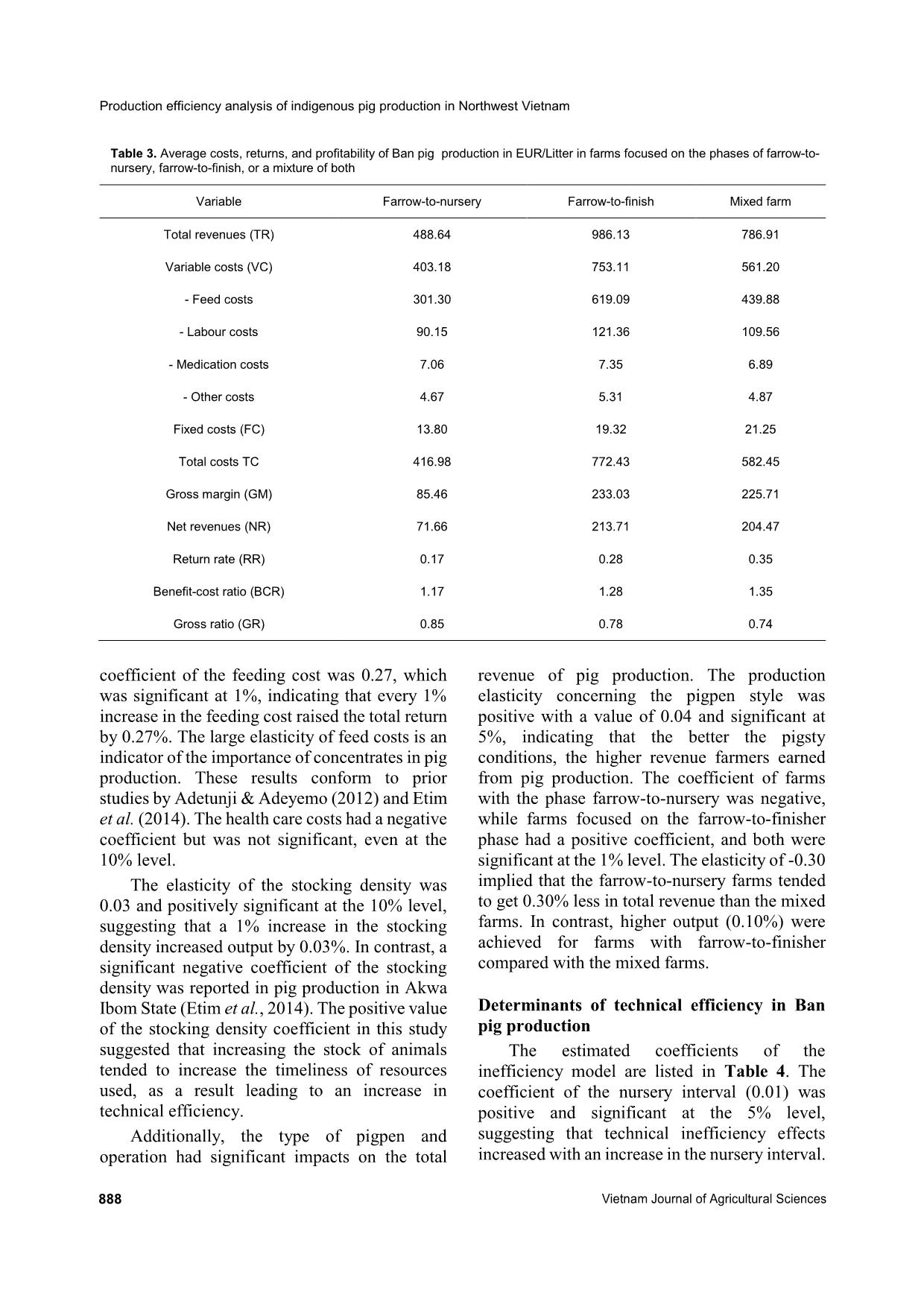

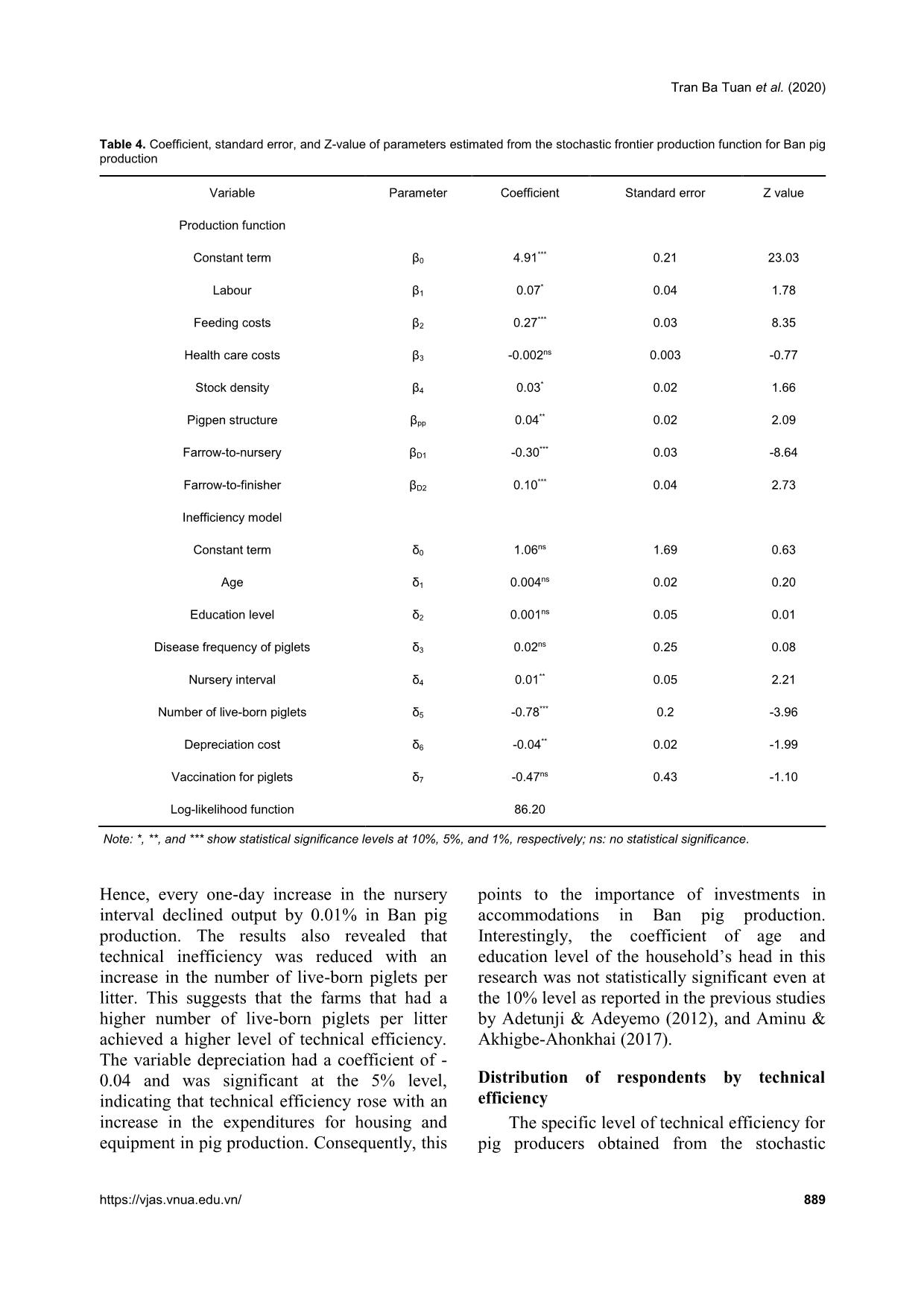

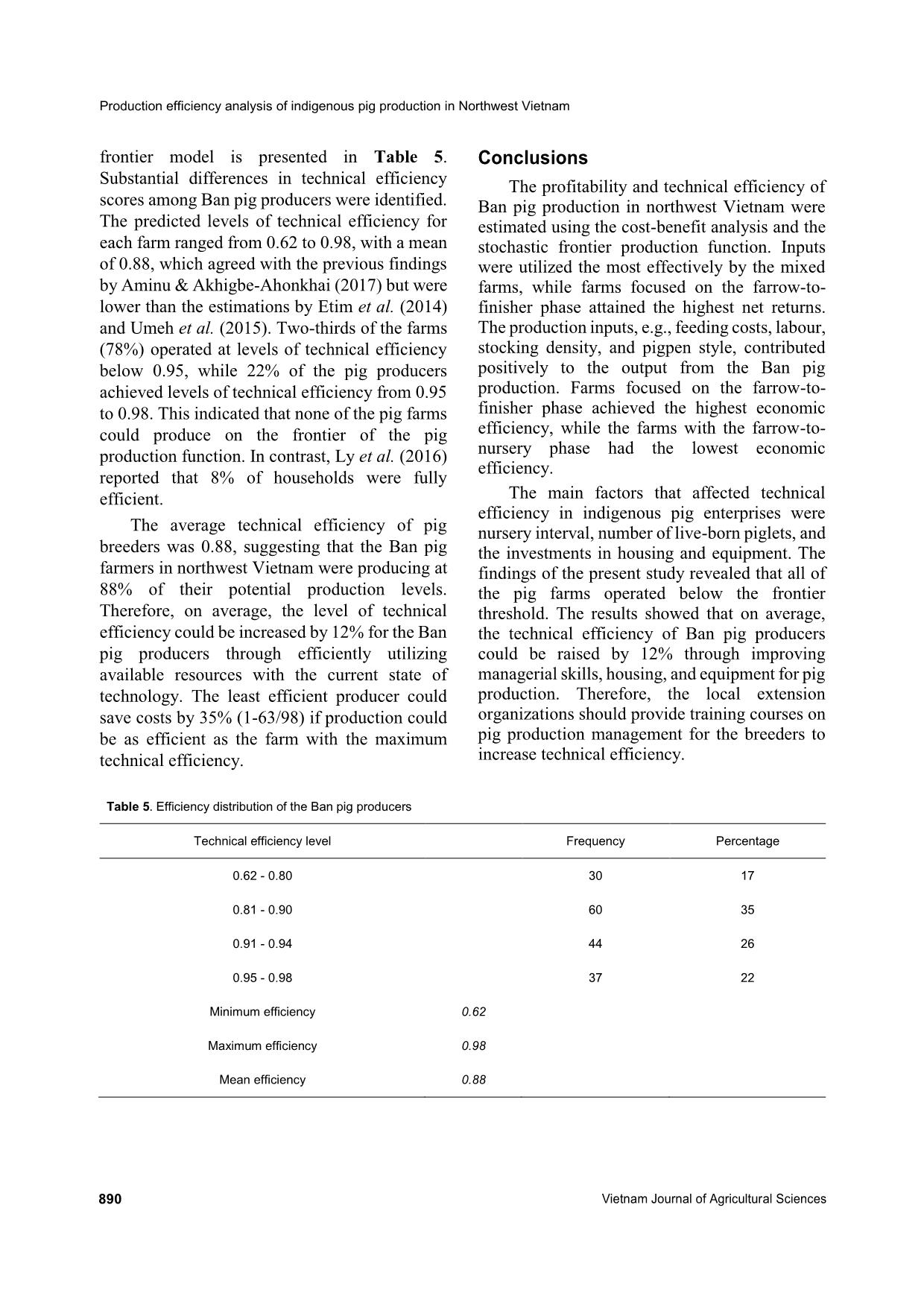

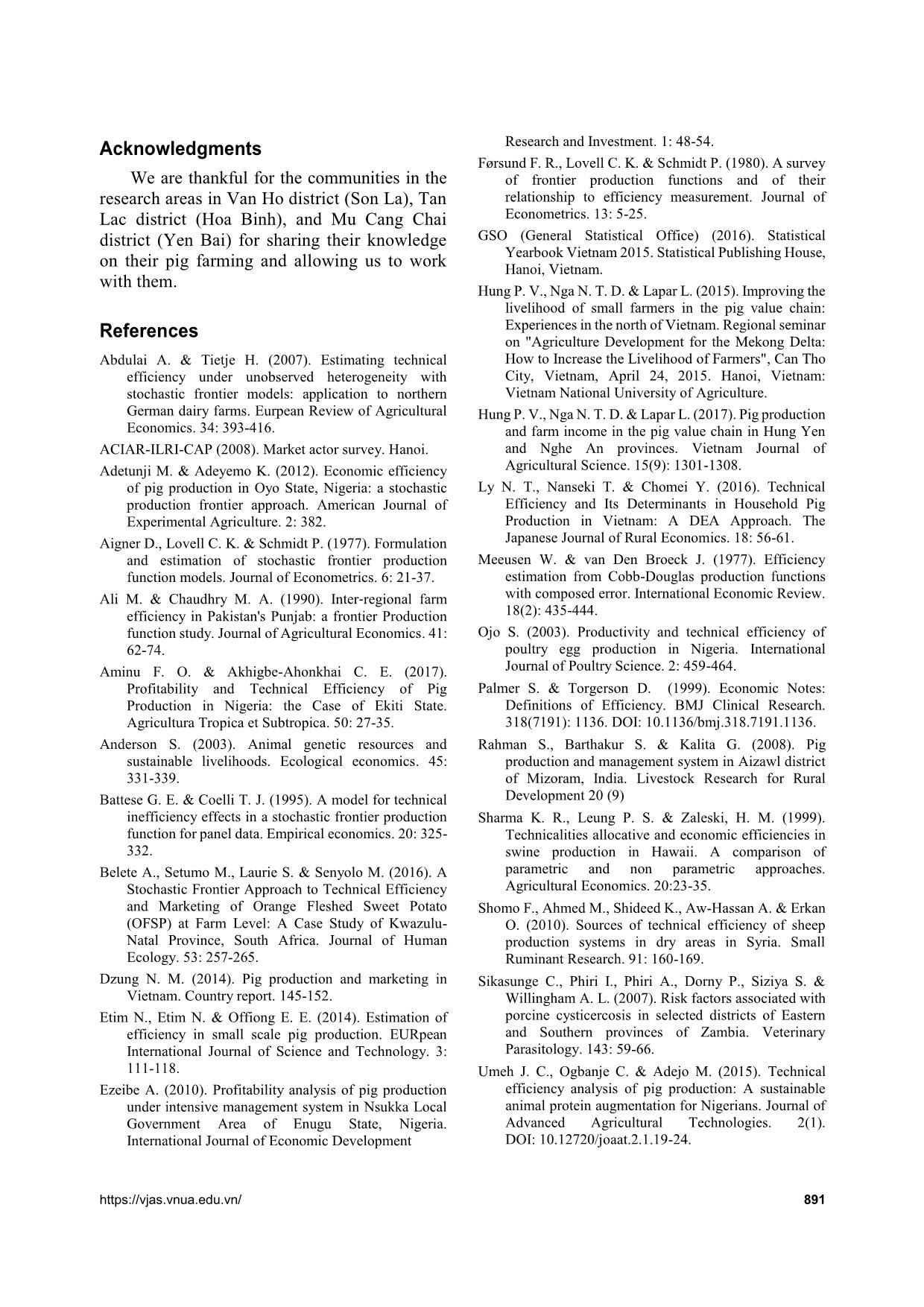

UR 213.71 per litter, while the profit decreased to EUR 75.46 per litter if farms only concentrated on the phase of farrow-to-nursery. However, the rate of return in the farms that mixed both phases (0.35) was higher than the farms only undertaking one phase, i.e., farrow-to-finish (0.28) or farrow-to- nursery (0.17). Also, the gross ratios of the three types of farms were 0.74, 0.78, and 0.85, suggesting that for every EUR 1 return from the pig production system, EUR 0.74, EUR 0.78, and EUR 0.85 were spent by the farmers in the mixed, farrow-to-finish, and farrow-to-nursery farms, respectively. This implies that pig producers from mixed farms used inputs more efficiently than others. Parameters of the production factors Parameters estimated from the stochastic frontier production function are presented in Table 4. The results revealed that the coefficients of most of the inputs were statistically significant at different levels, except for the health care costs. The coefficient of labour was positive with a value of 0.07, which was significant at 10%. This means that a 1% increase in the man-day increased the total revenue by 0.07% when other factors were kept constant. This finding is in line with research on the profitability and technical efficiency of pig production in Ekiti State (Aminu and Akhigbe-Ahonkhai, 2017), and the study on efficiency in small-scale pig production in Akwa Ibom State (Etim et al., 2014). The Production efficiency analysis of indigenous pig production in Northwest Vietnam 888 Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Sciences Table 3. Average costs, returns, and profitability of Ban pig production in EUR/Litter in farms focused on the phases of farrow-to- nursery, farrow-to-finish, or a mixture of both Variable Farrow-to-nursery Farrow-to-finish Mixed farm Total revenues (TR) 488.64 986.13 786.91 Variable costs (VC) 403.18 753.11 561.20 - Feed costs 301.30 619.09 439.88 - Labour costs 90.15 121.36 109.56 - Medication costs 7.06 7.35 6.89 - Other costs 4.67 5.31 4.87 Fixed costs (FC) 13.80 19.32 21.25 Total costs TC 416.98 772.43 582.45 Gross margin (GM) 85.46 233.03 225.71 Net revenues (NR) 71.66 213.71 204.47 Return rate (RR) 0.17 0.28 0.35 Benefit-cost ratio (BCR) 1.17 1.28 1.35 Gross ratio (GR) 0.85 0.78 0.74 coefficient of the feeding cost was 0.27, which was significant at 1%, indicating that every 1% increase in the feeding cost raised the total return by 0.27%. The large elasticity of feed costs is an indicator of the importance of concentrates in pig production. These results conform to prior studies by Adetunji & Adeyemo (2012) and Etim et al. (2014). The health care costs had a negative coefficient but was not significant, even at the 10% level. The elasticity of the stocking density was 0.03 and positively significant at the 10% level, suggesting that a 1% increase in the stocking density increased output by 0.03%. In contrast, a significant negative coefficient of the stocking density was reported in pig production in Akwa Ibom State (Etim et al., 2014). The positive value of the stocking density coefficient in this study suggested that increasing the stock of animals tended to increase the timeliness of resources used, as a result leading to an increase in technical efficiency. Additionally, the type of pigpen and operation had significant impacts on the total revenue of pig production. The production elasticity concerning the pigpen style was positive with a value of 0.04 and significant at 5%, indicating that the better the pigsty conditions, the higher revenue farmers earned from pig production. The coefficient of farms with the phase farrow-to-nursery was negative, while farms focused on the farrow-to-finisher phase had a positive coefficient, and both were significant at the 1% level. The elasticity of -0.30 implied that the farrow-to-nursery farms tended to get 0.30% less in total revenue than the mixed farms. In contrast, higher output (0.10%) were achieved for farms with farrow-to-finisher compared with the mixed farms. Determinants of technical efficiency in Ban pig production The estimated coefficients of the inefficiency model are listed in Table 4. The coefficient of the nursery interval (0.01) was positive and significant at the 5% level, suggesting that technical inefficiency effects increased with an increase in the nursery interval. Tran Ba Tuan et al. (2020) https://vjas.vnua.edu.vn/ 889 Table 4. Coefficient, standard error, and Z-value of parameters estimated from the stochastic frontier production function for Ban pig production Variable Parameter Coefficient Standard error Z value Production function Constant term β0 4.91 *** 0.21 23.03 Labour β1 0.07 * 0.04 1.78 Feeding costs β2 0.27 *** 0.03 8.35 Health care costs β3 -0.002 ns 0.003 -0.77 Stock density β4 0.03 * 0.02 1.66 Pigpen structure βpp 0.04 ** 0.02 2.09 Farrow-to-nursery βD1 -0.30 *** 0.03 -8.64 Farrow-to-finisher βD2 0.10 *** 0.04 2.73 Inefficiency model Constant term δ0 1.06 ns 1.69 0.63 Age δ1 0.004 ns 0.02 0.20 Education level δ2 0.001 ns 0.05 0.01 Disease frequency of piglets δ3 0.02 ns 0.25 0.08 Nursery interval δ4 0.01 ** 0.05 2.21 Number of live-born piglets δ5 -0.78 *** 0.2 -3.96 Depreciation cost δ6 -0.04 ** 0.02 -1.99 Vaccination for piglets δ7 -0.47 ns 0.43 -1.10 Log-likelihood function 86.20 Note: *, **, and *** show statistical significance levels at 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively; ns: no statistical significance. Hence, every one-day increase in the nursery interval declined output by 0.01% in Ban pig production. The results also revealed that technical inefficiency was reduced with an increase in the number of live-born piglets per litter. This suggests that the farms that had a higher number of live-born piglets per litter achieved a higher level of technical efficiency. The variable depreciation had a coefficient of - 0.04 and was significant at the 5% level, indicating that technical efficiency rose with an increase in the expenditures for housing and equipment in pig production. Consequently, this points to the importance of investments in accommodations in Ban pig production. Interestingly, the coefficient of age and education level of the household’s head in this research was not statistically significant even at the 10% level as reported in the previous studies by Adetunji & Adeyemo (2012), and Aminu & Akhigbe-Ahonkhai (2017). Distribution of respondents by technical efficiency The specific level of technical efficiency for pig producers obtained from the stochastic Production efficiency analysis of indigenous pig production in Northwest Vietnam 890 Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Sciences frontier model is presented in Table 5. Substantial differences in technical efficiency scores among Ban pig producers were identified. The predicted levels of technical efficiency for each farm ranged from 0.62 to 0.98, with a mean of 0.88, which agreed with the previous findings by Aminu & Akhigbe-Ahonkhai (2017) but were lower than the estimations by Etim et al. (2014) and Umeh et al. (2015). Two-thirds of the farms (78%) operated at levels of technical efficiency below 0.95, while 22% of the pig producers achieved levels of technical efficiency from 0.95 to 0.98. This indicated that none of the pig farms could produce on the frontier of the pig production function. In contrast, Ly et al. (2016) reported that 8% of households were fully efficient. The average technical efficiency of pig breeders was 0.88, suggesting that the Ban pig farmers in northwest Vietnam were producing at 88% of their potential production levels. Therefore, on average, the level of technical efficiency could be increased by 12% for the Ban pig producers through efficiently utilizing available resources with the current state of technology. The least efficient producer could save costs by 35% (1-63/98) if production could be as efficient as the farm with the maximum technical efficiency. Conclusions The profitability and technical efficiency of Ban pig production in northwest Vietnam were estimated using the cost-benefit analysis and the stochastic frontier production function. Inputs were utilized the most effectively by the mixed farms, while farms focused on the farrow-to- finisher phase attained the highest net returns. The production inputs, e.g., feeding costs, labour, stocking density, and pigpen style, contributed positively to the output from the Ban pig production. Farms focused on the farrow-to- finisher phase achieved the highest economic efficiency, while the farms with the farrow-to- nursery phase had the lowest economic efficiency. The main factors that affected technical efficiency in indigenous pig enterprises were nursery interval, number of live-born piglets, and the investments in housing and equipment. The findings of the present study revealed that all of the pig farms operated below the frontier threshold. The results showed that on average, the technical efficiency of Ban pig producers could be raised by 12% through improving managerial skills, housing, and equipment for pig production. Therefore, the local extension organizations should provide training courses on pig production management for the breeders to increase technical efficiency. Table 5. Efficiency distribution of the Ban pig producers Technical efficiency level Frequency Percentage 0.62 - 0.80 30 17 0.81 - 0.90 60 35 0.91 - 0.94 44 26 0.95 - 0.98 37 22 Minimum efficiency 0.62 Maximum efficiency 0.98 Mean efficiency 0.88 https://vjas.vnua.edu.vn/ 891 Acknowledgments We are thankful for the communities in the research areas in Van Ho district (Son La), Tan Lac district (Hoa Binh), and Mu Cang Chai district (Yen Bai) for sharing their knowledge on their pig farming and allowing us to work with them. References Abdulai A. & Tietje H. (2007). Estimating technical efficiency under unobserved heterogeneity with stochastic frontier models: application to northern German dairy farms. Eurpean Review of Agricultural Economics. 34: 393-416. ACIAR-ILRI-CAP (2008). Market actor survey. Hanoi. Adetunji M. & Adeyemo K. (2012). Economic efficiency of pig production in Oyo State, Nigeria: a stochastic production frontier approach. American Journal of Experimental Agriculture. 2: 382. Aigner D., Lovell C. K. & Schmidt P. (1977). Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. Journal of Econometrics. 6: 21-37. Ali M. & Chaudhry M. A. (1990). Inter‐regional farm efficiency in Pakistan's Punjab: a frontier Production function study. Journal of Agricultural Economics. 41: 62-74. Aminu F. O. & Akhigbe-Ahonkhai C. E. (2017). Profitability and Technical Efficiency of Pig Production in Nigeria: the Case of Ekiti State. Agricultura Tropica et Subtropica. 50: 27-35. Anderson S. (2003). Animal genetic resources and sustainable livelihoods. Ecological economics. 45: 331-339. Battese G. E. & Coelli T. J. (1995). A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic frontier production function for panel data. Empirical economics. 20: 325- 332. Belete A., Setumo M., Laurie S. & Senyolo M. (2016). A Stochastic Frontier Approach to Technical Efficiency and Marketing of Orange Fleshed Sweet Potato (OFSP) at Farm Level: A Case Study of Kwazulu- Natal Province, South Africa. Journal of Human Ecology. 53: 257-265. Dzung N. M. (2014). Pig production and marketing in Vietnam. Country report. 145-152. Etim N., Etim N. & Offiong E. E. (2014). Estimation of efficiency in small scale pig production. EURpean International Journal of Science and Technology. 3: 111-118. Ezeibe A. (2010). Profitability analysis of pig production under intensive management system in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria. International Journal of Economic Development Research and Investment. 1: 48-54. Førsund F. R., Lovell C. K. & Schmidt P. (1980). A survey of frontier production functions and of their relationship to efficiency measurement. Journal of Econometrics. 13: 5-25. GSO (General Statistical Office) (2016). Statistical Yearbook Vietnam 2015. Statistical Publishing House, Hanoi, Vietnam. Hung P. V., Nga N. T. D. & Lapar L. (2015). Improving the livelihood of small farmers in the pig value chain: Experiences in the north of Vietnam. Regional seminar on "Agriculture Development for the Mekong Delta: How to Increase the Livelihood of Farmers", Can Tho City, Vietnam, April 24, 2015. Hanoi, Vietnam: Vietnam National University of Agriculture. Hung P. V., Nga N. T. D. & Lapar L. (2017). Pig production and farm income in the pig value chain in Hung Yen and Nghe An provinces. Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Science. 15(9): 1301-1308. Ly N. T., Nanseki T. & Chomei Y. (2016). Technical Efficiency and Its Determinants in Household Pig Production in Vietnam: A DEA Approach. The Japanese Journal of Rural Economics. 18: 56-61. Meeusen W. & van Den Broeck J. (1977). Efficiency estimation from Cobb-Douglas production functions with composed error. International Economic Review. 18(2): 435-444. Ojo S. (2003). Productivity and technical efficiency of poultry egg production in Nigeria. International Journal of Poultry Science. 2: 459-464. Palmer S. & Torgerson D. (1999). Economic Notes: Definitions of Efficiency. BMJ Clinical Research. 318(7191): 1136. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.318.7191.1136. Rahman S., Barthakur S. & Kalita G. (2008). Pig production and management system in Aizawl district of Mizoram, India. Livestock Research for Rural Development 20 (9) Sharma K. R., Leung P. S. & Zaleski, H. M. (1999). Technicalities allocative and economic efficiencies in swine production in Hawaii. A comparison of parametric and non parametric approaches. Agricultural Economics. 20:23-35. Shomo F., Ahmed M., Shideed K., Aw-Hassan A. & Erkan O. (2010). Sources of technical efficiency of sheep production systems in dry areas in Syria. Small Ruminant Research. 91: 160-169. Sikasunge C., Phiri I., Phiri A., Dorny P., Siziya S. & Willingham A. L. (2007). Risk factors associated with porcine cysticercosis in selected districts of Eastern and Southern provinces of Zambia. Veterinary Parasitology. 143: 59-66. Umeh J. C., Ogbanje C. & Adejo M. (2015). Technical efficiency analysis of pig production: A sustainable animal protein augmentation for Nigerians. Journal of Advanced Agricultural Technologies. 2(1). DOI: 10.12720/joaat.2.1.19-24.

File đính kèm:

production_efficiency_analysis_of_indigenous_pig_production.pdf

production_efficiency_analysis_of_indigenous_pig_production.pdf