Improving agricultural value chain financing: A case study of Seng Cu rice chain in Lao Cai province, Vietnam

Nowadays, agricultural value chain financing (AVCF) is considered

an effective agricultural financing approach in the world; however,

its prevalence is still limited in developing countries like Vietnam.

This paper aimed to analyze the financial gap between the demands

and the actual credit obtained of the Seng Cu (SC) rice chain

participants in Lao Cai province, Vietnam. Cross-sectional data were

collected from 160 face-to-face interviews with SC rice producers

and in-depth interviews with 31 other stakeholders involved in the

chain (demand-side) as well as the representatives of district-branch

banks (supply-side) in 2016-2017. Overall, almost all chain actors

had high financial demands, especially upland rice producers and the

leading chain actor (Tien Phong Cooperative). However, they faced

many credit constraints related to the strict risk-avoidance strategy

and the collateral requirement of the banks. Even though the SC rice

chain confirmed its high potential and many supportive linkages

among participants were developed, the decision-making of banks on

credit disbursements still depended on the individual capability of

each chain actor rather than the entire chain. Thus, some

recommendations for policymakers, producers, and agribusinesses

are suggested to enhance the financial sources going in the chain and

the effectiveness of chain actors in the locality. Specifically, banks

need to assess the creditworthiness of farmers and agribusinesses

through the enhancement of repayment capability; while the public

sector needs to enact new regulations encouraging the participation

of banks in the chain.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Trang 8

Trang 9

Trang 10

Tải về để xem bản đầy đủ

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Improving agricultural value chain financing: A case study of Seng Cu rice chain in Lao Cai province, Vietnam

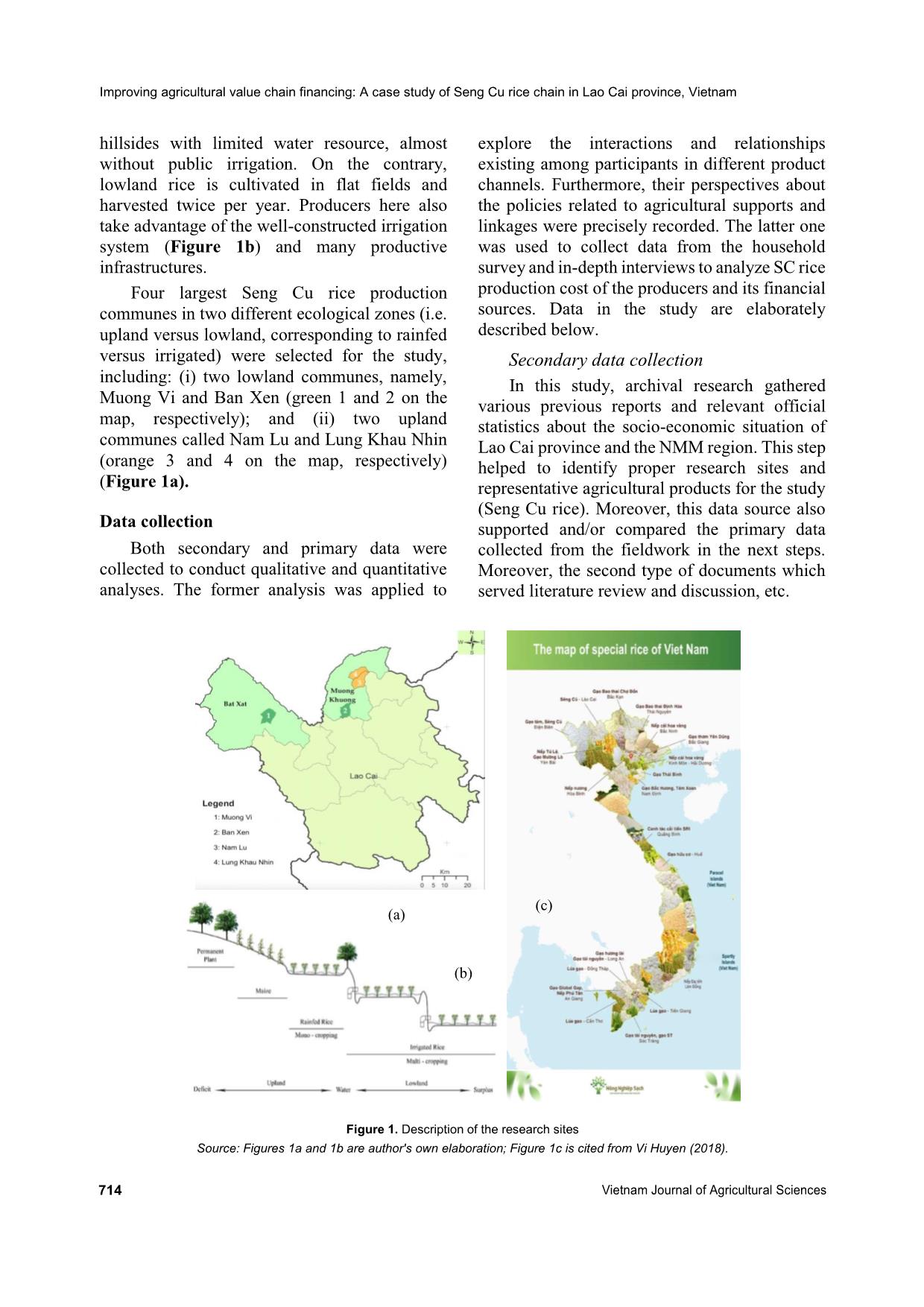

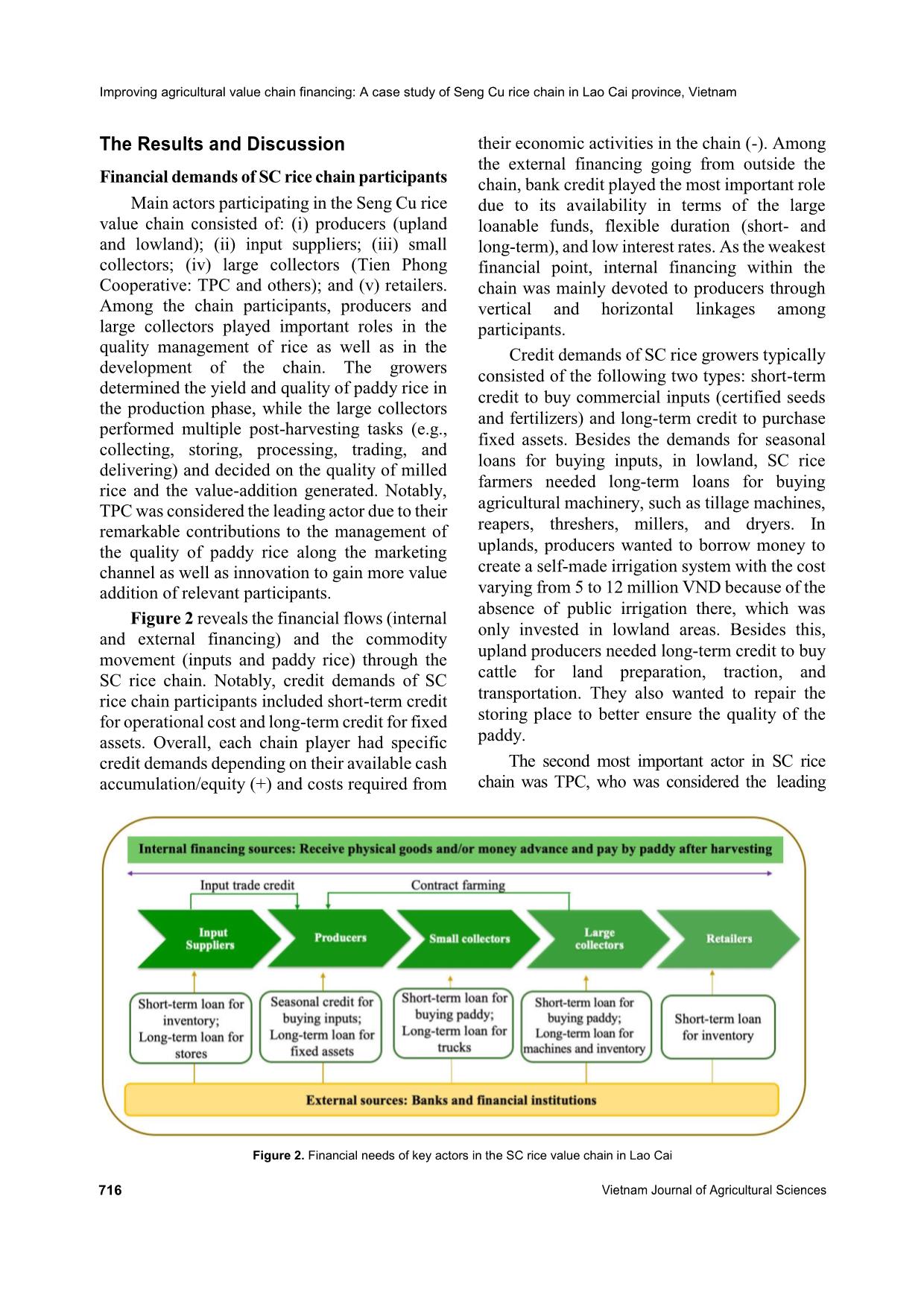

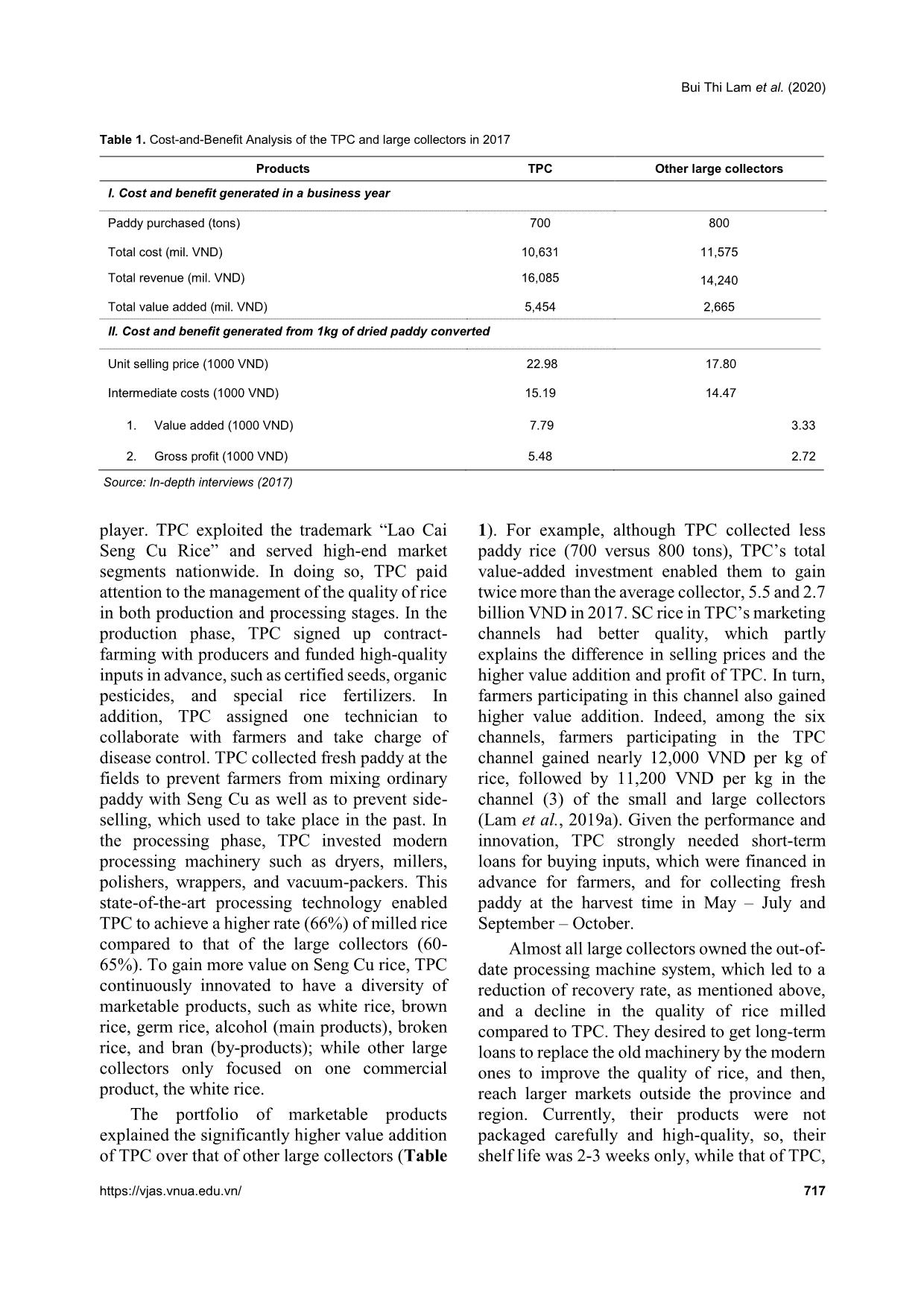

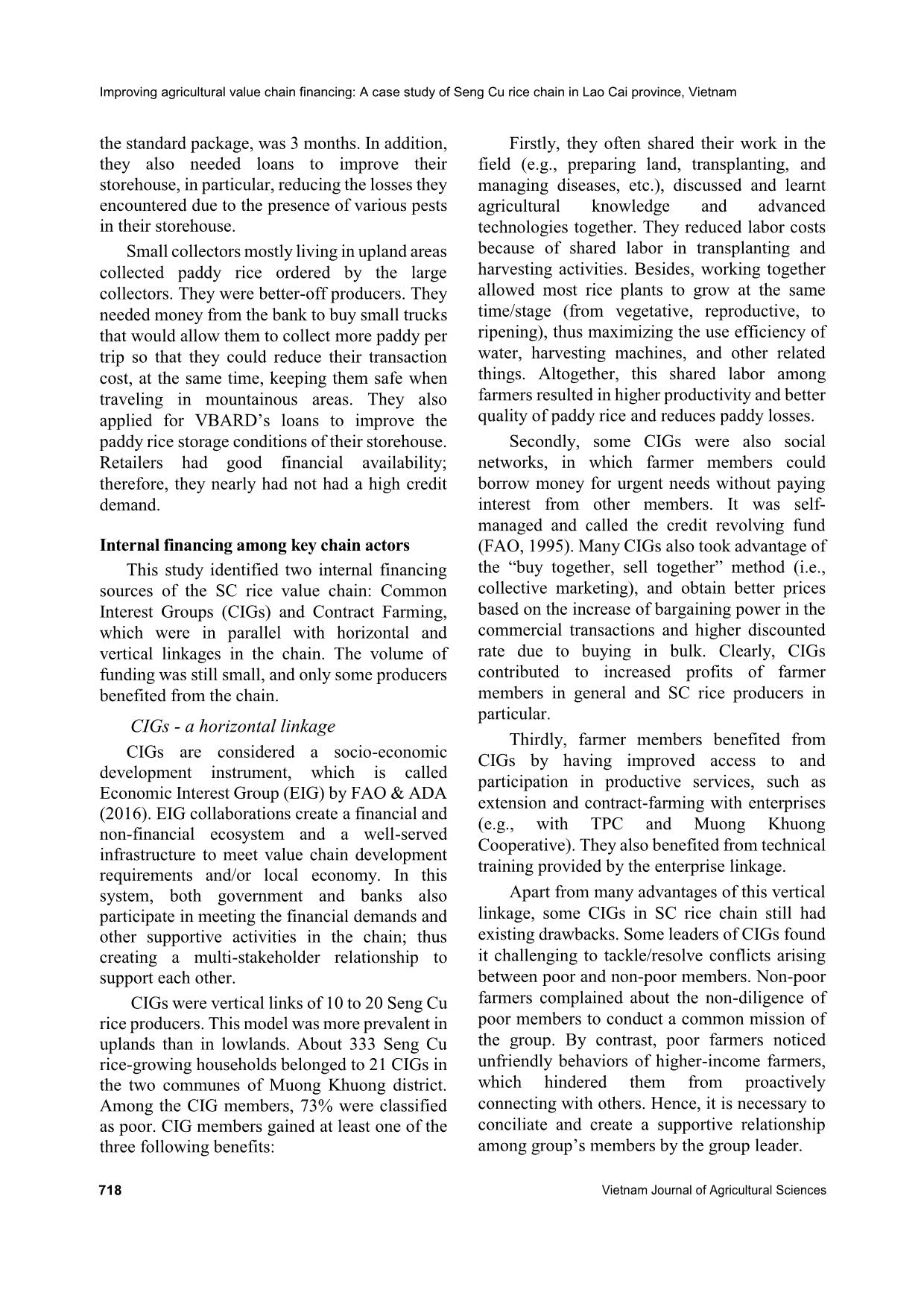

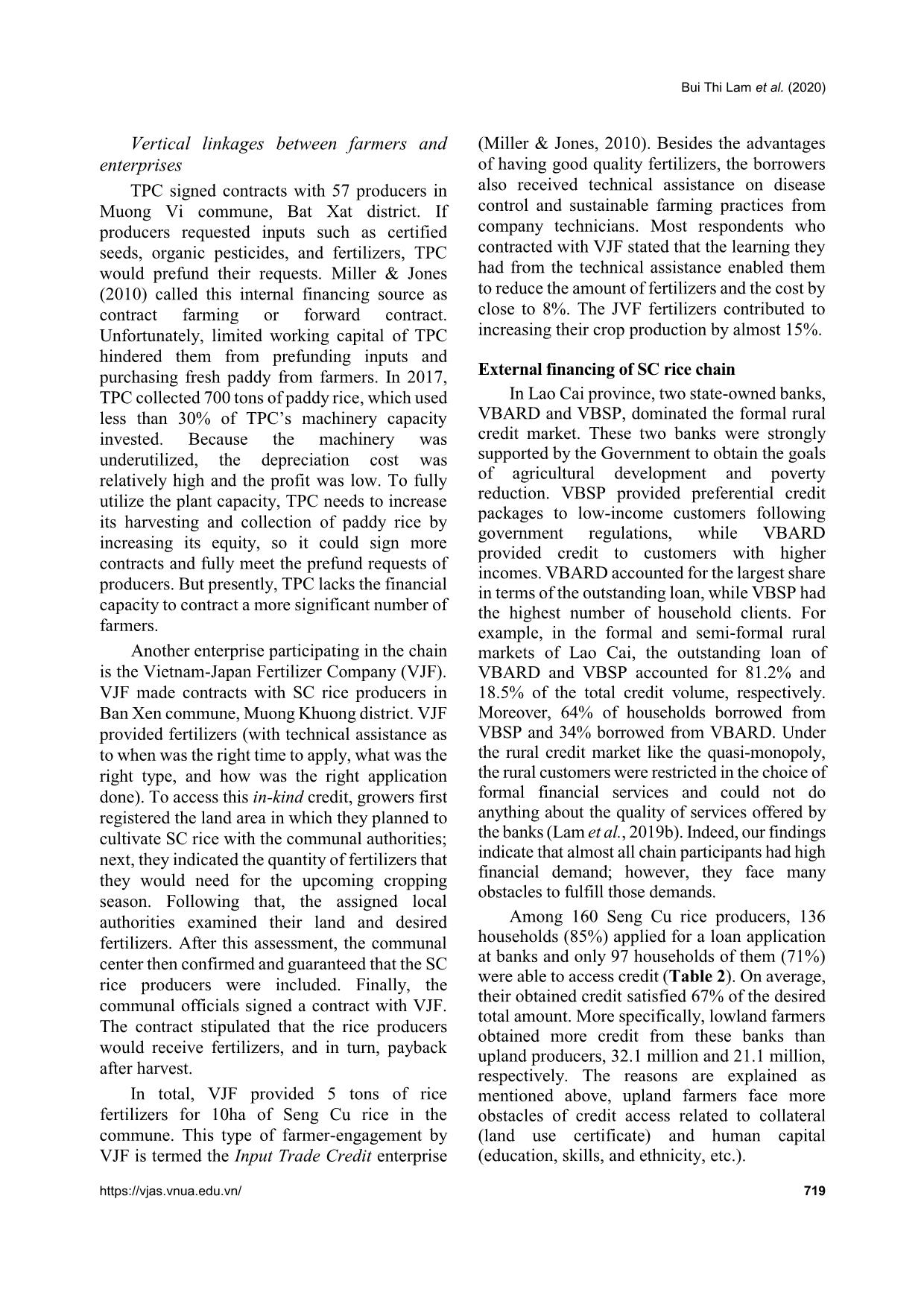

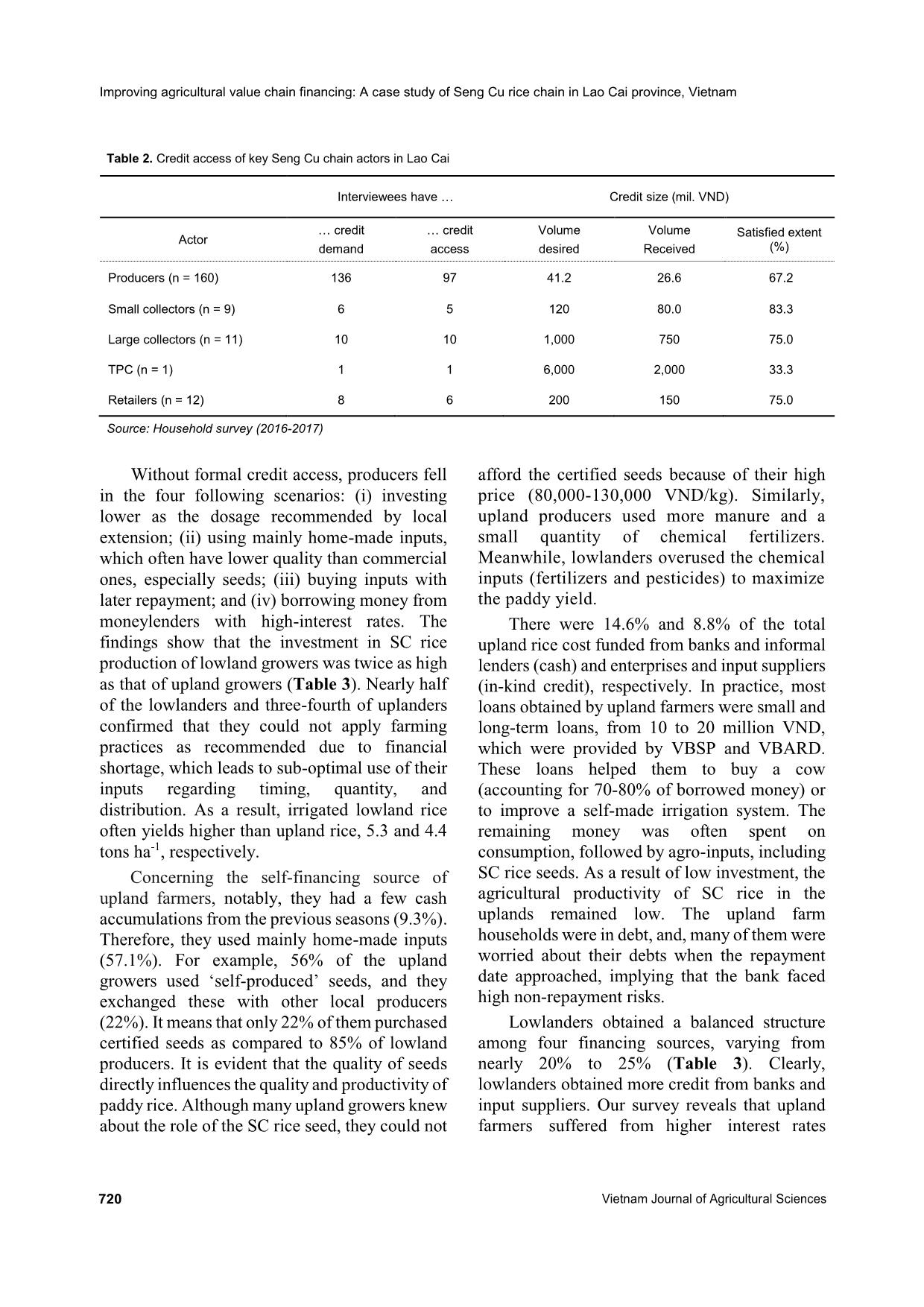

amily, but they did not obatain LUCs yet. As a result, 2-4 households owned one family LUC together; therefore, only one household could use the LUC as collateral. In uplands, local farmers had to face more credit constraints than lowlanders. In-depth interviews with VBARD’s representatives showed that lending on upland areas facede higher transaction costs, higher natural risks, and lower value at the real-estate market. These are the reasons why bank officials consider lending to upland farmers to be riskier than lending to lowland farmers. Besides constraints related to collateral, social and human capital also became credit constraints of many farmers. Both banks, VBARD and VBSP, disbursed loans to farmers mainly by the lending group method; in which, the assessments of local authorities (the leader of lending group, the head of the village, the head of Mass Organization, and the representative of the commune) played a crucial role in screening the loans before disbursement and banks’ decision-making. Claudio (2017) also indicated that lending group assessments led to difficulties for bank officers to evaluate applicants (i.e., they “look the same”) and to make the right decisions on credit disbursement. Concerning human capital, which was the third factor affecting credit access, lowlanders had more advantages than uplanders. For example, they had higher educational levels, more labour and fewer dependents, more diversity of non-farm income, and higher available financing as the bank’s requirement (Lam et al., 2018). Dufhues (2007) also concluded that credit constraints of farmers in mountainous areas of Vietnam were linked with low/none of the following three types of capital: physical (collateral), social (network among their community), and human capital (education, knowledge, and skills, etc.). The participation of VBARD in the chain was able to help remove various financial challenges and promote their economic performance that was limited and the effectiveness that was still low. In doing so, VBARD needs to change the mind-set to focus more on potential agricultural chains, like the Seng Cu rice chain, and assess directly the repayment capability of customers through reliable information, not just focus on collateral as currently. To sum up, this study shows that difficult banking access (i.e., external financial sources) seems to be the biggest obstacle for SC chain actors to reach their optimal performance. Thus, improving credit access is considered as the entry point for breaking the cycle: low investment, low Bui Thi Lam et al. (2020) https://vjas.vnua.edu.vn/ 723 productivity, low efficiency, and low income/profit. Indeed, financial availability can help farmers to optimally apply inputs in terms of quantity, quality, and appropriate time. Similarly, TPC can also enhance efficiency and increase income by expanding farming contracts with farmers, purchasing the volume of paddy desired, as well as developing marketing channels (e-commerce, retailing, and wholesaling). For other large buyers, they can improve the processing machine system to improve SC rice quality and reduce wastage. To access banking credit, it is necessary to collaborate among relevant actors, including chain actors (farmers and agribusinesses), banks, and the public sector, which is presented in the underlying implications. Conclusions and Implications Conclusions It is a common belief that the right finance at the right time contributes to greater efficiency and better quality of agricultural products; hence, increased incomes of relevant chain participants. This is clearly seen in the case of SC rice, where almost all chain actors had high financial needs but their credit demands had not been met. Indeed, they faced financial constraints due to a lack of collateral, and the strict risk-avoidance strategy of the banks, especially VBARD. Overall, 85% of the 160 SC rice producers had financial demands, while 71% successfully applied for a bank loan with an average amount of 26.6 million VND, which was lower than their desired amount (41.2 million VND). Lowland producers obtained a higher loan size than upland producers, 32.2 and 21.1 million VND, respectively. Lowlanders have more advantages in funding their rice cultivation, not only having higher self-financing ability, but also having easier access to bank credit and in-kind credit provided by enterprises (i.e., input trade credit and contract-farming). By contrast, upland producers needed both short-term credit for commercial inputs and long- term credit for buying livestock and maintaining the irrigation system of their terraced plots. Unfortunately, they received smaller credit volume than the amount that they desired. They often bought livestock, followed by goods for consumption, and then, agro-inputs, including SC rice seeds. Currently, the home-made inputs account for 66% of the production cost; neither their investments nor productivity and income have improved clearly. Many households were worried about how they would repay their debts, which implies the non-repayment risk of banks. Likewise, TPC, the leading actor in the chain, needs more capital to enlarge contracts with producers, and consequently increasing paddy collected, which would allow them to maximize the use of their machines. TPC collects fresh paddy and makes payments in the field to prevent growers from mixing ordinary rice with SC rice and from breaking the contract by side- selling. The five months from harvest till sale, TPC would need 6 billion VND, but they could only borrow 2 billion VND. To compensate for this deficit, TPC partly fills its financial shortage by borrowing money from private lenders who charge a much higher interest rate. This does not only reduce the profit of TPC, but also keeps the benefit of farmers being low. In contrast, the small and large collectors face constraints in accessing credit to build warehouses and fund part of their trade. Implications An effective value chain financing depends on four actors, including: (1) producers; (2) agribusinesses; (3) rural banks; and (4) policy- makers. Therefore, the paper suggests relevant recommendations for these key actors as follows. To handle difficulties in accessing banking credit, farmers’ creditworthiness needs to be assessed by banks. To do that, they have to improve their repayment capability through their appropriate farming practices and financial management. Besides this, farmers must comply with the contractual agreements signed with banks and/or enterprises, especially the term of the appropriate loan use. To enhance their creditworthiness, agribusinesses need to reduce their three existing weaknesses by: (i) Standardizing the financial reports according to the current regulations; (ii) A study on the tax obligations and perceived tax compliance of small and medium enterprises 724 Vietnam Journal of Agricultural Sciences Using more banking service in transactions, which allows banks to capture cash flows of agribusiness; and (iii) Improving the management capability and the effectiveness of loan use. Rural banks should focus on their legal target customers, namely farmers, agribusinesses, and agriculture allied activities. Rural banks also need to participate in the chain and assign credit officer(s) to gather accurate information about the main key chain actors and to estimate their creditworthiness based on the repayment capability of individual actors as well as the potential of the whole chain. To date, the Vietnamese Government issued the Decree No. 98/2018/ND-CP regarding incentive policies for value chain linkages among farmers, enterprises, and other chain actors. This regulation, however, still does not mention the participation of rural banks in the chain, especially VBARD. Practically, financial availability in the chain does not change without external funds from banks, and chain actors often need credit access to optimize their performance. Therefore, we suggest that the public sector needs to enact new legal framework that requires/encourages the participation of banks in the chain. Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and valuable comments on the research topic. The analysis expressed here is the authors’ alone. References AfDB (2013). Agricultural Value Chain Financing (AVCF) and Development for Enhanced Export Competitiveness. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Docum ents/Project-and- Operations/Agricultural_Value_Chain_Financing__A VCF__and_Development_for_Enhanced_Export_Co mpetitiveness.pdf on May 10, 2017. Claudio G.-V. (2017). The barriers to agricultural financing and the emergence of new models of financial intermediation for the sector. In: Emilio Hernández (Ed.) Innovative risk management strategies in rural and agriculture finance – The Asian experience. 15-28. Retrieved from on August 6, 2018. Coates M., Kitchen R., Kebbell G., Vignon C., Guillemain C. & Hofmeister R. (2011). Financing agricultural value chains in Africa: A synthesis of four country case studies. Making finance work for Africa. Eschborn- Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit [GIZ]. Retrieved from chains/library/details/en/c/267127/ on August 9, 2017. Cochran W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd Edition). John Wiley & Sons. New York, United State. 448 pages. De La O Campos A. P., Villani C., Davis B. & Takagi M. (2018). Ending extreme poverty in rural areas – Sustaining livelihoods to leave no one behind. Rome, FAO. 84 pages. Retrieved from on March, 2019. Dufhues T. (2007). Accessing rural finance: The rural financial market in Northern Vietnam. Studies on the Agricultural and Food Sector in Central and Eastern Europe. etrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46472781_ Accessing_rural_finance_The_rural_financial_market _in_Northern_Vietnam on May 5, 2017. Emerson R. M., Fretz R. I. & Shaw L. L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press, United State. FAO (1995). History of the credit revolving fund. Retrieved from on May 14, 2019. FAO & ADA (2016). Innovations for inclusive agricultural finance and risk mitigation mechanisms –The case of Tamwil El Fellah in Morocco, by Ramirez, J. & Hernandez, E. Rome, Italy. Retrieved from on September 20, 2017. Fetterman D. M. (2009). Ethnography: Step-by-step (Applied Social Research Methods) (3rd Edition). 200 pages. Sage Publications, United State. GRiSP (2013). Rice almanac, Source book for one of the most important economic activities on earth (Fourth edition). Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute. 283 pages. (Global Rice Science Partnership). Retrieved from on August 19, 2018. GSO (2017). Statistical Yearbook of Vietnam: Social- Economical Data from 1990 to 2017. General Statistis Office. Retrieved from https://www.gso.gov.vn/default_en.aspx?tabid=515&i dmid=5&ItemID=18533 on May 6, 2018 (in Vietnamese). GSO (2018). Results of the Vietnam Household Living Standard Survey (VHLSS) 2018. General Statistis Office. Vietnam. Retrieved from Bui Thi Lam et al. (2020) https://vjas.vnua.edu.vn/ 725 https://www.gso.gov.vn/wp- content/uploads/2020/05/VHLSS2018.pdf on May 10, 2018 (in Vietnamese). HLPE (2013). Investing in smallholder agriculture for food security. Retrieved from i2953e.pdf on May 10, 2017. Vi Huyen (2018). Special rice map in Vietnam. Retrieved from https://vnexpress.net/thoi-su/ban-do-cac-loai- gao-dac-san-o-viet-nam-3768497.html on March 23, 2019 (in Vietnamese). Kelly D. (2005). Power and participation: participatory resource management in south-west Queensland. Retrieved from https://openresearch- repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/47415/13/01fro nt.pdf on September 12, 2019. Lam B. T., Cuong T. H., Azadi H. & Lebailly P. (2018). Improving the Technical Efficiency of Sengcu Rice Producers through Better Financial Management and Sustainable Farming Practices in Mountainous Areas of Vietnam. Sustainability. 10(7): 1-19. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072279 on August 22, 2018. Lam B. T., Cuong T. H., Ho T. M. H., Eiichi K. & Philippe L. (2019a). Realisation of Higher Value Added of Seng Cu Rice Value Chain in Vietnam. 52-86. Retrieved from https://www.eria.org/uploads/media/8.RPR_FY2018_ 05_Chapter_3.pdf on March 5, 2019. Lam B. T., Hop H. T. M., Philippe B., Dogot T., Tran H. C. & Lebailly P. (2019b). Impacts of Credit Access on Agricultural Production and Rural Household’s Welfares in Northern Mountains of Vietnam. Asian Social Science. 15(7): 119-133. Retrieved from iew/0/39949 on September 7, 2019. Miller C. (2012). Agricultural value chain finance strategy and design: Technical Note. Retrieved from https://www.ifad.org/en/web/knowledge/publication/a sset/39181165 on December 9, 2017. Miller C. & Jones L. (2010). Agricultural value chain finance: Tools and lessons. Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved from on December 10, 2017. Miyata S., Minot N. & Hu D. (2009). Impact of contract farming on income: linking small farmers, packers, and supermarkets in China. World Development. 37(11): 1781-1790. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.025 on September 12, 2018. Olomola A. S. (2010). Models of contract farming for pro- poor growth in Nigeria. IPPG Briefing Note. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08b18 ed915d3cfd000b1e/bp34.pdf on September 12, 2018. Rapsomanikis G. (2015). The economic lives of smallholder farmers: An analysis based on household data from nine countries. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. Retrieved from on March 22, 2019. Saigenji Y. & Zeller M. (2009). Effect of contract farming on productivity and income of small holders: The case of tea production in North-Western Vietnam. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228542523_ Effect_of_contract_farming_on_productivity_and_inc ome_of_small_holders_The_case_of_tea_production _in_north-western_Vietnam on March 10, 2019. Springer-Heinze A. (2018). ValueLinks 2.0. Manual on Sustainable Value Chain Development, GIZ Eschborn, 2 volumes. Volume 1. Retrieved from https://www.valuelinks.org/material/manual/ValueLin ks-Manual-2.0-Vol-1-January-2018.pdf on December 12, 2018.

File đính kèm:

improving_agricultural_value_chain_financing_a_case_study_of.pdf

improving_agricultural_value_chain_financing_a_case_study_of.pdf