Codeswitching among first-year English majored students at Hanoi National University of education and their views on this linguistic phenomenon

Codeswitching, a product of bilingualism, is popular among bilinguals.

Many researchers and educators consider codeswitching as a downgrading factor

to the target language learning process while others perceive them as a natural

product of bilingualism. This study investigates the frequency of codeswitching

used among students and their attitudes towards this phenomenon. The results

show that students tend to codeswitch more frequently in group-works. Moreover,

although students feel bad when they codeswitch, they have more relaxed attitudes

towards their peers’ codeswitching. In addition, the findings demonstrate that the

ease of knowledge transference is the main reason for codeswitching and the fear of

not getting progress if using too much Vietnamese in English classes is the major

concern of students.

Trang 1

Trang 2

Trang 3

Trang 4

Trang 5

Trang 6

Trang 7

Tóm tắt nội dung tài liệu: Codeswitching among first-year English majored students at Hanoi National University of education and their views on this linguistic phenomenon

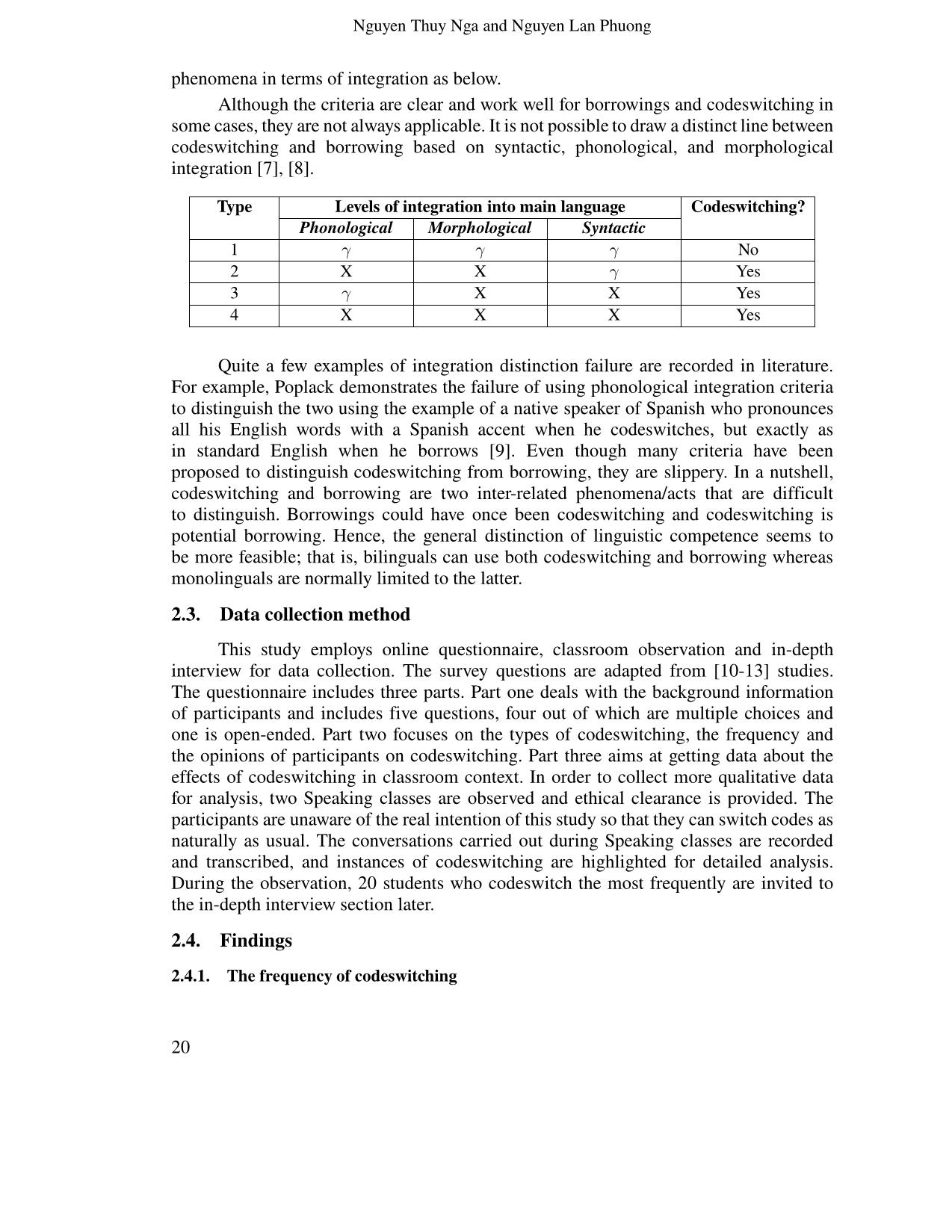

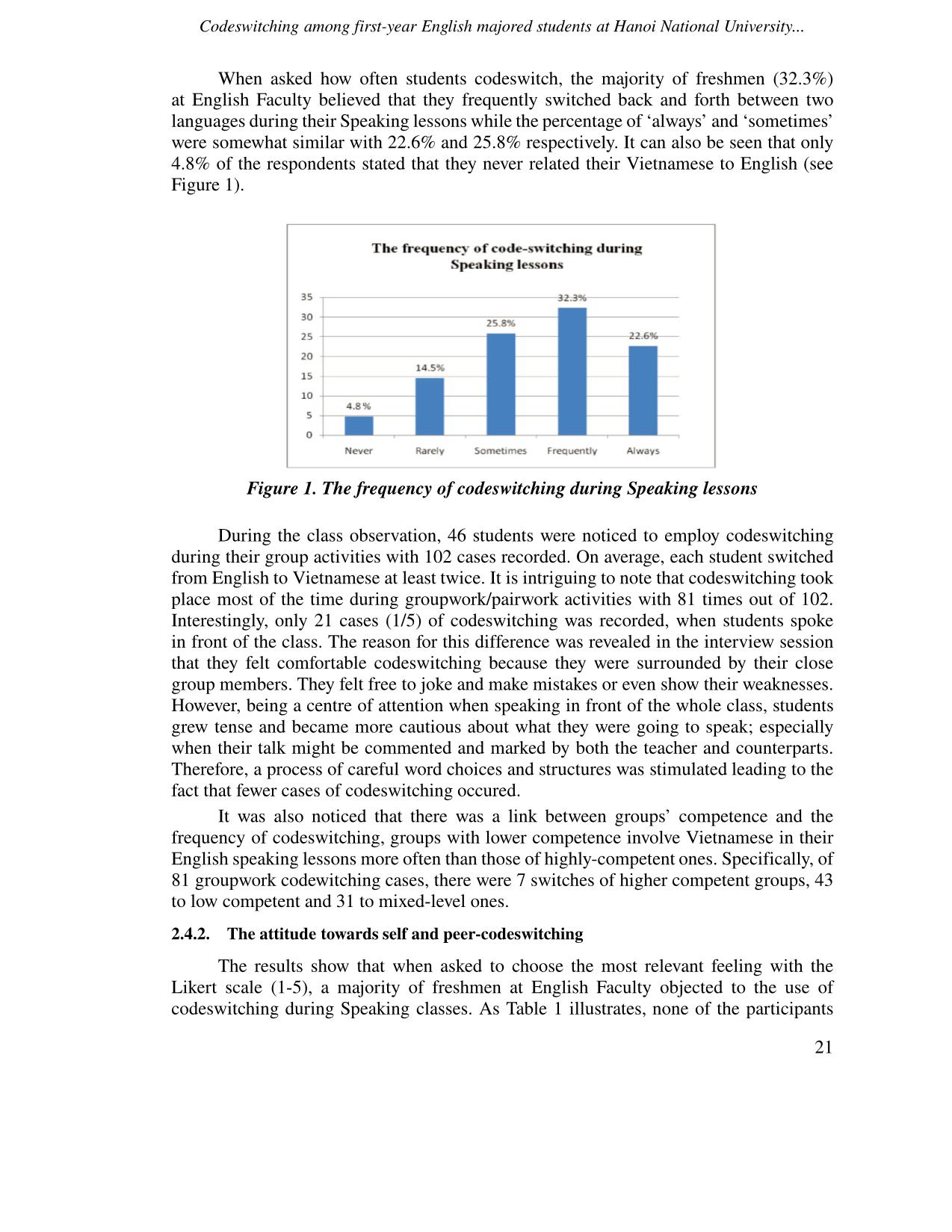

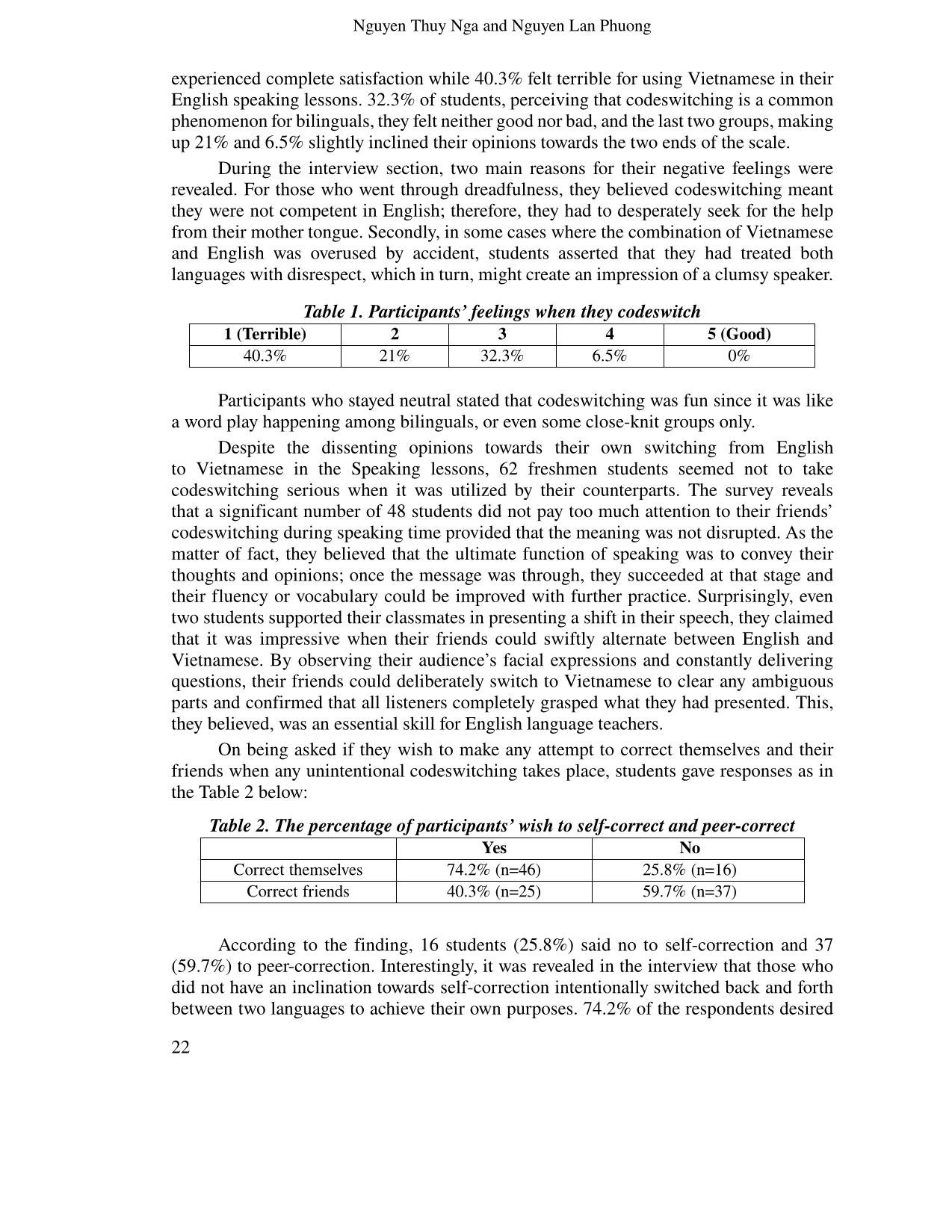

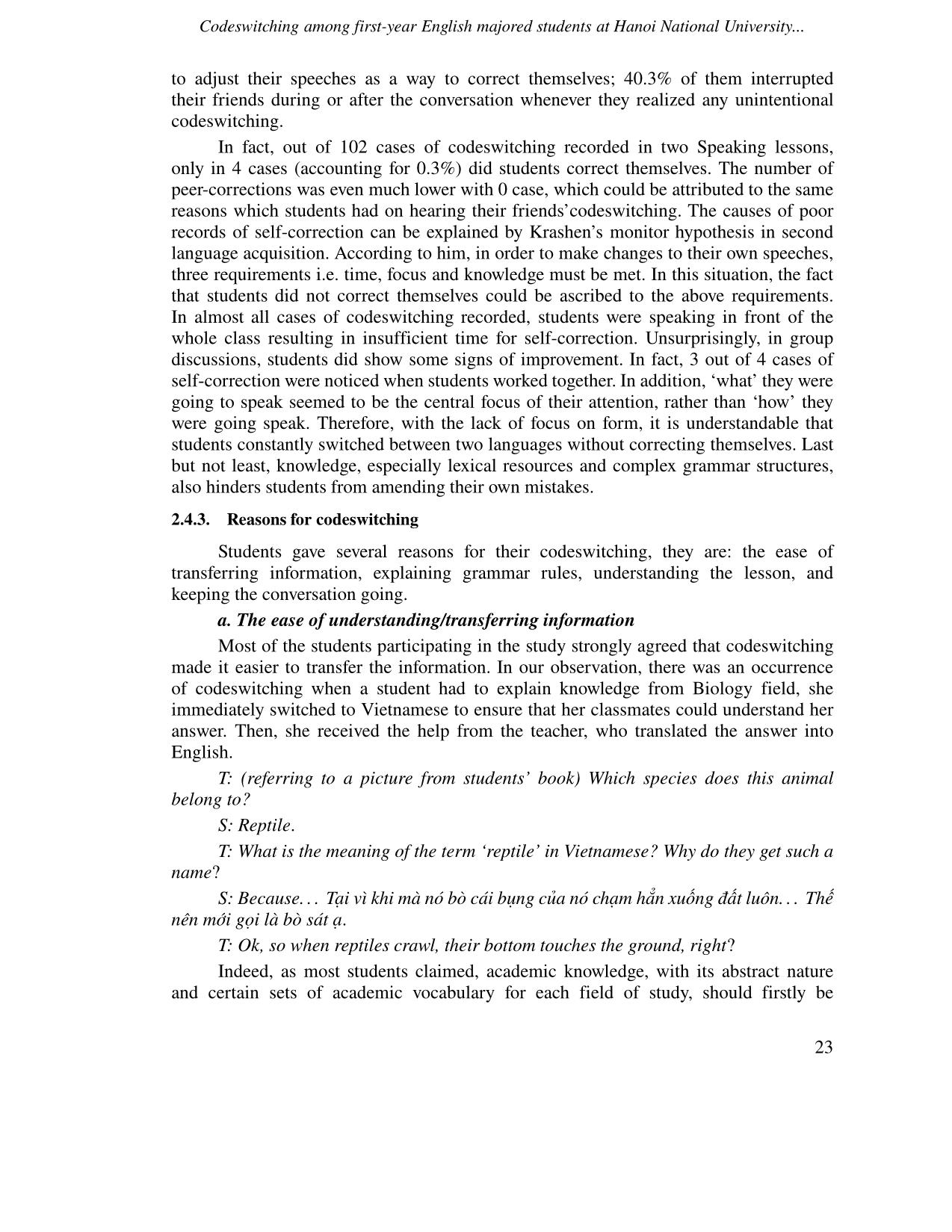

gn traits. Poplack believes that: ‘Codeswitching is the juxtaposition of sentences or sentence fragments, each of which is internally consistent with the morphological and syntactic (and optionally, phonological) rules of the language of its provenance’ [6]. Poplack proposes morphosyntactic and phonological integration into the main language in a codeswitched utterance which makes up the majority of phonological and morphological features of the discourse. She establishes a table to differentiate two 19 Nguyen Thuy Nga and Nguyen Lan Phuong phenomena in terms of integration as below. Although the criteria are clear and work well for borrowings and codeswitching in some cases, they are not always applicable. It is not possible to draw a distinct line between codeswitching and borrowing based on syntactic, phonological, and morphological integration [7], [8]. Type Levels of integration into main language Codeswitching? Phonological Morphological Syntactic 1 γ γ γ No 2 X X γ Yes 3 γ X X Yes 4 X X X Yes Quite a few examples of integration distinction failure are recorded in literature. For example, Poplack demonstrates the failure of using phonological integration criteria to distinguish the two using the example of a native speaker of Spanish who pronounces all his English words with a Spanish accent when he codeswitches, but exactly as in standard English when he borrows [9]. Even though many criteria have been proposed to distinguish codeswitching from borrowing, they are slippery. In a nutshell, codeswitching and borrowing are two inter-related phenomena/acts that are difficult to distinguish. Borrowings could have once been codeswitching and codeswitching is potential borrowing. Hence, the general distinction of linguistic competence seems to be more feasible; that is, bilinguals can use both codeswitching and borrowing whereas monolinguals are normally limited to the latter. 2.3. Data collection method This study employs online questionnaire, classroom observation and in-depth interview for data collection. The survey questions are adapted from [10-13] studies. The questionnaire includes three parts. Part one deals with the background information of participants and includes five questions, four out of which are multiple choices and one is open-ended. Part two focuses on the types of codeswitching, the frequency and the opinions of participants on codeswitching. Part three aims at getting data about the effects of codeswitching in classroom context. In order to collect more qualitative data for analysis, two Speaking classes are observed and ethical clearance is provided. The participants are unaware of the real intention of this study so that they can switch codes as naturally as usual. The conversations carried out during Speaking classes are recorded and transcribed, and instances of codeswitching are highlighted for detailed analysis. During the observation, 20 students who codeswitch the most frequently are invited to the in-depth interview section later. 2.4. Findings 2.4.1. The frequency of codeswitching 20 Codeswitching among first-year English majored students at Hanoi National University... When asked how often students codeswitch, the majority of freshmen (32.3%) at English Faculty believed that they frequently switched back and forth between two languages during their Speaking lessons while the percentage of ‘always’ and ‘sometimes’ were somewhat similar with 22.6% and 25.8% respectively. It can also be seen that only 4.8% of the respondents stated that they never related their Vietnamese to English (see Figure 1). Figure 1. The frequency of codeswitching during Speaking lessons During the class observation, 46 students were noticed to employ codeswitching during their group activities with 102 cases recorded. On average, each student switched from English to Vietnamese at least twice. It is intriguing to note that codeswitching took place most of the time during groupwork/pairwork activities with 81 times out of 102. Interestingly, only 21 cases (1/5) of codeswitching was recorded, when students spoke in front of the class. The reason for this difference was revealed in the interview session that they felt comfortable codeswitching because they were surrounded by their close group members. They felt free to joke and make mistakes or even show their weaknesses. However, being a centre of attention when speaking in front of the whole class, students grew tense and became more cautious about what they were going to speak; especially when their talk might be commented and marked by both the teacher and counterparts. Therefore, a process of careful word choices and structures was stimulated leading to the fact that fewer cases of codeswitching occured. It was also noticed that there was a link between groups’ competence and the frequency of codeswitching, groups with lower competence involve Vietnamese in their English speaking lessons more often than those of highly-competent ones. Specifically, of 81 groupwork codewitching cases, there were 7 switches of higher competent groups, 43 to low competent and 31 to mixed-level ones. 2.4.2. The attitude towards self and peer-codeswitching The results show that when asked to choose the most relevant feeling with the Likert scale (1-5), a majority of freshmen at English Faculty objected to the use of codeswitching during Speaking classes. As Table 1 illustrates, none of the participants 21 Nguyen Thuy Nga and Nguyen Lan Phuong experienced complete satisfaction while 40.3% felt terrible for using Vietnamese in their English speaking lessons. 32.3% of students, perceiving that codeswitching is a common phenomenon for bilinguals, they felt neither good nor bad, and the last two groups, making up 21% and 6.5% slightly inclined their opinions towards the two ends of the scale. During the interview section, two main reasons for their negative feelings were revealed. For those who went through dreadfulness, they believed codeswitching meant they were not competent in English; therefore, they had to desperately seek for the help from their mother tongue. Secondly, in some cases where the combination of Vietnamese and English was overused by accident, students asserted that they had treated both languages with disrespect, which in turn, might create an impression of a clumsy speaker. Table 1. Participants’ feelings when they codeswitch 1 (Terrible) 2 3 4 5 (Good) 40.3% 21% 32.3% 6.5% 0% Participants who stayed neutral stated that codeswitching was fun since it was like a word play happening among bilinguals, or even some close-knit groups only. Despite the dissenting opinions towards their own switching from English to Vietnamese in the Speaking lessons, 62 freshmen students seemed not to take codeswitching serious when it was utilized by their counterparts. The survey reveals that a significant number of 48 students did not pay too much attention to their friends’ codeswitching during speaking time provided that the meaning was not disrupted. As the matter of fact, they believed that the ultimate function of speaking was to convey their thoughts and opinions; once the message was through, they succeeded at that stage and their fluency or vocabulary could be improved with further practice. Surprisingly, even two students supported their classmates in presenting a shift in their speech, they claimed that it was impressive when their friends could swiftly alternate between English and Vietnamese. By observing their audience’s facial expressions and constantly delivering questions, their friends could deliberately switch to Vietnamese to clear any ambiguous parts and confirmed that all listeners completely grasped what they had presented. This, they believed, was an essential skill for English language teachers. On being asked if they wish to make any attempt to correct themselves and their friends when any unintentional codeswitching takes place, students gave responses as in the Table 2 below: Table 2. The percentage of participants’ wish to self-correct and peer-correct Yes No Correct themselves 74.2% (n=46) 25.8% (n=16) Correct friends 40.3% (n=25) 59.7% (n=37) According to the finding, 16 students (25.8%) said no to self-correction and 37 (59.7%) to peer-correction. Interestingly, it was revealed in the interview that those who did not have an inclination towards self-correction intentionally switched back and forth between two languages to achieve their own purposes. 74.2% of the respondents desired 22 Codeswitching among first-year English majored students at Hanoi National University... to adjust their speeches as a way to correct themselves; 40.3% of them interrupted their friends during or after the conversation whenever they realized any unintentional codeswitching. In fact, out of 102 cases of codeswitching recorded in two Speaking lessons, only in 4 cases (accounting for 0.3%) did students correct themselves. The number of peer-corrections was even much lower with 0 case, which could be attributed to the same reasons which students had on hearing their friends’codeswitching. The causes of poor records of self-correction can be explained by Krashen’s monitor hypothesis in second language acquisition. According to him, in order to make changes to their own speeches, three requirements i.e. time, focus and knowledge must be met. In this situation, the fact that students did not correct themselves could be ascribed to the above requirements. In almost all cases of codeswitching recorded, students were speaking in front of the whole class resulting in insufficient time for self-correction. Unsurprisingly, in group discussions, students did show some signs of improvement. In fact, 3 out of 4 cases of self-correction were noticed when students worked together. In addition, ‘what’ they were going to speak seemed to be the central focus of their attention, rather than ‘how’ they were going speak. Therefore, with the lack of focus on form, it is understandable that students constantly switched between two languages without correcting themselves. Last but not least, knowledge, especially lexical resources and complex grammar structures, also hinders students from amending their own mistakes. 2.4.3. Reasons for codeswitching Students gave several reasons for their codeswitching, they are: the ease of transferring information, explaining grammar rules, understanding the lesson, and keeping the conversation going. a. The ease of understanding/transferring information Most of the students participating in the study strongly agreed that codeswitching made it easier to transfer the information. In our observation, there was an occurrence of codeswitching when a student had to explain knowledge from Biology field, she immediately switched to Vietnamese to ensure that her classmates could understand her answer. Then, she received the help from the teacher, who translated the answer into English. T: (referring to a picture from students’ book) Which species does this animal belong to? S: Reptile. T: What is the meaning of the term ‘reptile’ in Vietnamese? Why do they get such a name? S: Because. . . Tại vì khi mà nó bò cái bụng của nó chạm hẳn xuống đất luôn. . . Thế nên mới gọi là bò sát ạ. T: Ok, so when reptiles crawl, their bottom touches the ground, right? Indeed, as most students claimed, academic knowledge, with its abstract nature and certain sets of academic vocabulary for each field of study, should firstly be 23 Nguyen Thuy Nga and Nguyen Lan Phuong comprehended in their mother tongue. There is a possibility that students might acquire some academic knowledge in Vietnamese; therefore, with the assistance of the background knowledge, the process of acquisition in the second language will definitely less time-consuming and more effective. As a result, many students confirmed that codeswitching was a choice to transfer the knowledge/information more easily. b. The ease of explaining/understanding grammar rules more precisely With regard to grammar, all students agreed that Vietnamese played an important role in making grammar points intelligible. They insisted that in speaking, grammar was one of the marking criteria. For that reason, it was believed that one of the responsibilities of teachers was to make sure that students could show an accurate and wide range of grammar structures in any kinds of speaking tests. Furthermore, Vietnamese is also utilized effectively to give examples and make comparison in grammar between two languages as in the following example. T: (checking students’ answer) You said ‘families of children’? Imagine we say ‘A man with money’. . . It means this man has some money, right?. . . It is similar. . . There are some children in the family, so we say ‘Families with children’, not ‘families of children’. It is true that we have the phrase ‘family of children’, but not in this case. S1: (turning to her friends to discuss) ‘with’ kiểu như ‘có’ trong Tiếng Việt mình ấy hả? In this case, student compared ‘with’ in English to ‘có’ in Vietnamese to deepen her understanding in grammar. Students also revealed that codeswitching in such situation could save a great amount of time so that they could focus more on other speaking skills. c. The ease of understanding the lesson correctly As students codeswitched to clear doubts and uncertainties, they agreed that codeswitching helped them understand the lessons more easily. In many cases recorded during observations, Vietnamese was used to clarify meaning. For example “short-sighted là gì thế?” or “Cô nói cái gì đấy?”. On the other hand, codeswitching had compensated for students’ lack of vocabulary; it was used to guarantee that everyone in class, even low level ones, could keep pace with the whole class. In addition, many students assumed that if words or phrases were repeated in Vietnamese after being presented in English, they were important ones. By switching back and forth between two languages, students expected to have key ideas highlighted and emphasized. d. The ease of keeping the conversation going The other benefit of codeswitching in speaking lessons that students claimed is to avoid interruption caused by linguistic deficiency and keep the conversation going smoothly. For example, when the teacher asked her students to talk about their father’s job with the person next to them, one of them codeswitched to Vietnamese as following: S: My father works on a farm. . . . And he raises. . . Raise đúng không hay là rise? Nuôi là raise đúng không? In the above example, as the student hesitated between ‘raise’ and ‘rise’, she switched to Vietnamese to receive constructive suggestions from her friends in order to make the correct choice of word. As a result, she successfully conveyed her intended 24

File đính kèm:

codeswitching_among_first_year_english_majored_students_at_h.pdf

codeswitching_among_first_year_english_majored_students_at_h.pdf